Week 2 - How To Hunt A Unicorn  It may be considered that the search for an agent or a publisher makes hunting for unicorns look like a stroll in the park. Why is this? Well, it is because the number of authors outnumbers the number of agents and publishers by a lot. When I say “a lot” I’m not thinking 2 to 1, 5 to 1 or even 10 to 1. I’m thinking of tens of thousands to one. And that’s just in the UK. Covid-19 has further increased the number of new authors as lots of people have had more time on their hands than they really want and writing that first novel is a good way of filling time. One of our own authors, Arabella Aristo (that’s a pen name, by the way) is one such example, as she was unable to work during lockdown. Writing a book has never been more popular and, thanks to platforms like Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), Lulu, Kobo, Smashwords and others, publishing a book has never been easier. But those are self-publishing sites. What has that got to do with agents and publishers? Well, every author who self-publishes first tries to publish by the traditional route. So – back to that SWAG (statistically wild-ass guess) of tens of thousands to one.  When you submit your manuscript (MS) to an agent or a publisher, you are adding to a reading pile that is already several feet thick. The agents and the publishers can therefore afford to be very choosey about which MS they consider and which they toss in the rubbish bin. Our blog last week was about making sure your book is ready to go to the agent/publisher by getting independent feedback on it before you submit it. Now you can start to see why this is so critical. Each “query” letter/email is a one-shot deal. If your book isn’t up to standard, you won’t get a second chance with that agent. But let’s look on the positive side. Your book is a modern classic and the feedback you have received suggests that it is going to win the Booker Prize. Most major publishing houses don’t accept submissions direct anymore. It costs too much to pay people to read them. They only deal with agents and it is the agent who reads the MS. So, you want to find an agent. How do you start? If you’ve been in any of the usual social media hangouts frequented by authors, you will have read a lot out about “elevator pitches” and crafting the perfect “query” letter. For the uninitiated, an elevator pitch is a short speech to tell someone about your book. Imagine you are in an elevator and an agent gets in with you and you have until the elevator reaches his/her floor to tell them about your book – less than a minute probably. Let’s do a reality check here. How likely is that to happen? Not very. So why waste precious time developing the perfect elevator pitch?  Ah, but you can also use it to pitch your book on social media, like Twitter or in your query letter (for the sake of simplicity, assume “letter” also means email). Twitter members even do days called #pitmad, where people pitch their books. No. Trust me on this, agents and publishers aren’t trawling social media looking for the next Hilary Mantel or J K Rowling. They don’t need to. And if you use your elevator pitch in your query letter by saying “it’s like Game of Thrones crossed with James Bond” it isn’t going to tell the agent enough to excite their attention – mainly because they’ve probably seen it before. There is a place for the elevator pitch, but it comes much later in the process. It is useful in marketing your book, but we’ll come back to that in a few week’s time. The query letter is in the same vein and many authors agonise over composing the perfect query letter. Don’t get stressed about this. If your work is good enough, the letter will be read even if it is written with a blunt crayon. OK, present yourself professionally, but the query letter doesn’t have to be perfect, it just has to introduce you to the agent or publisher. All it really has to say is “here’s my book, submitted in accordance with your submission guidelines”. I’ll return to submission guidelines later as they are quite important. How do you find an agent?  In the UK I would recommend you buy the latest edition of “The Writers’ ℇ Artists’ Yearbook”. In it you will find a section on agents, including contact addresses, website details and email addresses. There is now also a spin-off website which has some other useful resources https://www.writersandartists.co.uk/ For children’s writers, there is a subsidiary book, “The Children’s Writers’ ℇ Artists’ Yearbook”. The one thing you can guarantee is that all the agents and agencies listed in the Yearbook are reputable and have a track record in publishing. The downside is that every author wants the agent to represent them If you are reading this book outside of the UK then there is probably an equivalent book and/or website where you live, but you’ll need to Google it. Some entries give information about the genres the agent represents but others don’t, so you may have to do some further research online to narrow down the field to those agents who are most likely to be interested in your book. Some entries also list authors that the agent already represents, so look for names that write in the same genre as you. If there aren’t any, they may not be the right agent for you. Most agents and agencies have their own websites these days, which makes life a lot easier. Visit the website and see what they have to say about authors and genres. Big agencies will list all their agents and from that you will be able to identify the one who represents authors most like you. Sending your book to the wrong agent is only going to have one outcome and you don’t want it. Time spent on this sort of research is never wasted. It is better to spend an hour finding the right name at an agency than it is to spend 3 hours e-mailing all the names in the hope of hitting the right one. This is particularly important when it comes to non-fiction. Most agents who represent non-fiction authors deal with a very narrow range of work. Sending your biography to an agent who only deals with autobiographies is a complete waste of time.  Now we come to the submission guidelines, which I will abbreviate as SGLs. These tell you how to submit your work to the agent or agency. Read them, take note of the content and DO WHAT THEY SAY. The SGLs have been created for a reason and that reason is not so you can ignore them. Firstly, they tell you how many words or chapters to submit. Why is that important? Because if your work doesn’t get the agent excited within that wordcount, they won’t be interested in reading any further. So, if you’re not sure your book can grab the agent’s attention within that wordcount – there’s no point in submitting it. Your beta readers should be able to help you there; ask them how quickly they were hooked on your book? And if you aren’t confident that your book will gain the agent’s attention – you can do something about that before you submit your MS. If you don’t do anything about it, why are you wasting people’s time? One thing you can do while you are actually writing the book is to assume that the last book an agent accepted was exactly like yours. So why would they now want your book if they have just signed one just like it? In that case, how are you going to make your book different from the one he/she just accepted? When you have answered that question, do it! Make no mistake – originality sells.  The other thing about complying with the SGLs are that they show your ability to work with a team. There are authors who have a reputation for being “difficult to work with” (translation: they’re a total pain in the you-know-what). Let me just tell you that you have to be a pretty brilliant author to get away with that. For most authors, the agent – and any publisher they connect you to – wants to know that working with you will be a dream experience – not a nightmare on Elm Street. Adhering to the SGLs is your way of showing what a sweet natured, team player you are. And if you aren’t – fake it. Most SGLs ask for a synopsis of the rest of the book. This is so the agent can see how the story develops and comes to its conclusion. Now, two things about the synopsis:

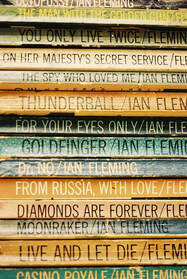

Here’s a blog from an experienced publisher about how to write a good synopsis. It is on the synopsis that you should be concentrating your time and effort – not elevator pitches or perfect query letters. There is a reason why the synopsis is usually limited in length and it is so the agent can see if you can express your thoughts concisely. If your synopsis rambles on for three or four pages, then your MS is also likely to ramble on (just like this blog). It is quite probable that the agent will read the synopsis before the MS, so you can see how you will start to influence their thinking if you get it right – or wrong. Agents and publishers want to form long term relationships with authors. Long term relationships spread over several books pay the bills year after year after year. This is where your query letter is important, unless they ask for a biography.  Tell them what plans you have for future books. Harper Lee may have written a 20th century classic, but she didn’t earn her agent or publisher much money after the initial sales surge. Nowadays she would be lucky to get a book deal if she said, “I’ve only got plans for one book”. Publishers particularly like series. If a series catches on, they become real money spinners; just ask J K Rowling and George R R Martin If you are asked for a biography, then keep it short and simple. Bullet points work best: name, age, family circumstances (married, single, children etc), education, current employment, hobbies and interests and, finally, plans for future books. Once you have selected your agents (note the plural) submit to several at the same time – I’d say at least 3 or 4. First of all, if you wait for each one in turn to get back to you before sending out the next query, you are going to be querying forever, Secondly, ideally you want to get into a bidding war, with agents vying over you and competing to give you the best deal so you will sign with them.  To start that bidding war you can’t get an acceptance and then query a second time, because that shows lack of integrity. You’ll lose that acceptance and you’ll probably put off the rest of the agent community. They do talk to each other and compare notes, you know. The next step for the agent after reading your initial query submission is to ask you for the full MS. It is very important for the MS to be ready to go. The agent isn’t going to wait for you to finish writing the book. They have a stack of other queries four feet high to be getting on with and by the time you have finished writing your MS, they’ve moved on and you’ve missed your big chance.  Now, inevitably, we get to what to do about rejections – because you will get rejections (or, worse, you won’t get a response at all). Legend has it that J K Rowling had 60 rejections before getting Harry Potter accepted. Whether that number is accurate I have no idea, but Rowling herself admits to being rejected by several agents before being signed by Christopher Little then, when she did find him, the book was rejected by 12 publishers before being taken up by Bloomsbury. And, of course, we all know that Decca Records rejected The Beatles, much to EMI’s profit. The main thing to bear in mind is that a rejection doesn’t mean your book is bad. Just remember what I said about tens of thousands of authors and only a handful of agents. Each agent may only take on one or two new clients a year and they will be the ones that don’t just stand out from the crowd, they are the ones that tower over the crowd. Agents rarely say why they are rejecting your book and, for all you know, your book may have been just a hair’s breadth away from being accepted. Send out your query letter again to the next batch of agents on your list. You never know which one is going to be the one who takes your book. But, in the end, you may get to the end of the list of agents without ever catching your unicorn. But that doesn’t mean you’ve reached the end of the road. Next week we’ll be taking a look at medium sized publishers and paid for publishing. We hope you have enjoyed this blog and found it informative. If you want to make sure you don't miss any future editions, please sign up to receive our newsletter. Just hit the button.

0 Comments

Week 1 - the start of the journey OK, you’ve spent weeks, months, or even years writing your book and now you’re ready to get it published. That’s great, but however hard you have worked in writing your book, publishing is going to be even harder work. At least, it is if you want to actually sell some copies of your book. That is what this weekly blog is all about. What to do and what not to do to get your book published – and then getting it to sell.. This blog will also cover self-publishing because, despite everything said against it, you can be a successful self-published author. But that’s a discussion for the future. It is a sad fact of life that no matter how good your book, you may not be able to find a big (or even medium) name publisher. There are hundreds of thousands of authors working right now and only a handful will ever end up with a publishing contract. So, if you can't get a publisher, self-publishing is about the only route you have left to you if you want your book to be read. And if you are self-publishing, you are going to have to know how to market your book because, believe it or not, no one is going to stumble across it by accident, which is probably why the Stumbleupon webiste closed down. From Week 4 onwards we are going to be focused mainly on marketing your book, so stick with us, or maybe sign-up for our Newsletter so you don't miss a single issue of this blog. First, Week 1, Lesson 1. NEVER PART WITH MONEY. As with all industries, there are a lot of sharks out there just waiting to pray on the unwary, the innocent and the naïve. Don’t let that be you. If anyone is asking you for money to publish your book, run away. Run away as fast as you can. This includes paying a “deposit to cover our work”. There will be times when you do have to pay for certain services and I’ll cover them at the relevant points, but for the moment be suspicious of anyone who asks you for money, especially if all you know about them is their website URL and e-mail address. If all you know about them is their Twitter username, be even more suspicious. Reputable publishers don’t take money up front. They take a risk that your work is going to earn them an income when it is published. You trust them to do a good job with your book and they take a risk that your book is going to sell. This is why it is so hard to get a publishing deal. Publishers are taking a risk on you, but they don’t want it to be too big a risk, so they look for the sure-fire successes. Nowadays they don’t have teams of people reading submissions for them, they rely on literary agents to offer them the best books. That means you actually have two hurdles to get over – finding an agent that will represent you and then the agent finding a publisher who will put the book out. But if you can get an agent, you are a long way down the road towards success because agents are really only interested in potential best-sellers. There are smaller publishers (like us) who accept submissions direct from authors but, of course, a small publisher has less money to spend on marketing your work, so your sales volumes are likely to reflect that. But we’ll get onto the pros and cons of using small publishers another week.  But now to the main topic for this week’s blog. How do you know if your book is good enough to be published? You may think you have written 100,000 words of literary perfection, but readers may think it is 100,000 words of dog excrement. To find out which it is, you need to get an unbiased view of how good your book is before you start sending it off to agents and/or publishers. You're only going to get one shot, so it has to be your best shot. There may be things about your book that you can fix quite easily and there may be things that need major re-writes. As a publisher we see a lot of manuscripts (MSs) and a lot of them leave us scratching our heads and wondering how anyone thought that what they had submitted was fit to be put in front of the reading public. They aren’t necessarily bad in terms of their plot and characters, but to be readable they need a whole lot of work. It is the main reason that so many authors get rejection emails/letters (sometimes they don’t hear anything back at all). So, you really have to be sure that your book is as close to being ready for publication as is humanly possible. A publisher’s editor will help you to polish your book, but they won’t re-write it for you. The editor will provide you with the polish and the duster, but you have to do the work. So you may as well knuckle down and get the work done upfront. Friends and family are unreliable sources of feedback when it comes to assessing how good your work is. They love you (probably) and they don’t want to hurt your feelings (also probably). So, their feedback may be less than totally honest. This is especially true of spouses/partners, who would rather not get into a row with you about whether or not your book is good, why it isn’t and how his/her mother warned him/her not to marry you (those sorts of rows tend to escalate). What you need is beta readers. These are members of the public (alpha readers would be friends and family) who will give you feedback in return for a free copy of your book. How do you find beta readers? On social media.  This is where Twitter and Facebook can be useful. Put out a post asking for beta readers and make up a shortlist from the replies (5 or 6 is usually enough but more is OK). Make sure you specify your genre. There’s no point in getting beta readers who mainly read thrillers if your book is a period romance. When you send the copy of your book, you need to:

When you get the answers, make sure you understand them (check back with the reader if you don’t) and then act on them. This is most important. There is little point in asking for feedback if you are going to ignore it. I have been a beta reader and fed back to an author and they totally ignored what I had to say. I don’t mean they didn’t accept my comments on what was wrong with the book; I mean they didn’t even correct the typos that I pointed out. This means allowing time in your publishing schedule to review and act on the feedback. So, if you are going to self-publish on a specific date, there’s no point in giving a “respond by” date for the day of publication. Plan for there being major changes needed and you won’t leave yourself short of time before publication. Certainly, don’t start “querying”* the book until you have made the necessary changes. After all, the whole object of the exercise is to improve your book, so it is more likely to be accepted when you do start querying. Finally, don’t get defensive. The beta reader is trying to help you. You may not like what they have fed back to you, but you asked for their opinion and they have given it. It’s not their fault if you wrote a book that they didn’t like. Take the feedback seriously. If you don’t like what was said – don’t get into an argument. Just thank the beta reader for their input (do that anyway, it’s good manners). If you don’t agree with the feedback that a beta reader has given you, then you don’t have to do anything. But if more than one beta reader has said the same, or at least similar, things then it is well worth taking some time to reflect on what has been said. If one person says something it might be discounted as “opinion” but if two people are saying the same, it may mean that changes need to be made. If three people are saying it – you have a problem and it needs fixing. Finally, if you have made changes, you should go back to the beta a reader that suggested them to see if they think you have made an improvement. There’s no need to send the whole book, just the relevant passages. There are people who provide a "paid for" beta reading service. One of our authors used one for one of his books and the feedback he got was very valuable. But check what they are offering (are they actually beta readers or are they “proof readers”**) and check to see what sort of reputation they have. Reputable providers will be only too glad to tell you which authors they’ve helped and you can check with the authors themselves by using their social media to contact them. You probably got into writing because you are also a reader – so why not be a beta reader yourself? Your opinion is as valid as anyone’s and it’s a great way to get free books and to discover new authors. It’s also good for your karma (if you believe in karma) to help others. You could start by being a beta reader for one of our authors. Their contact details can be found alongside their author profiles by clicking here. That’s it for this week. Next week we’ll be looking at how to find an agent or publisher. * Querying – the technical term used for approaching an agent or publisher. ** A proof reader is someone who checks the spelling and grammar in your work and looks for typos. They don’t provide any feedback on the quality of the writing. Now for the hard sell (well, maybe not so hard). You can find out all about the books we publish by clicking the button below. To make sure you don't miss any of the blogs in this series, sign up for our newsletter here.

|

AuthorThis blog is compiled and curated by the Selfishgenie publishing team. Archives

March 2025

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed