Write the book you want to read. It’s a bit of advice most authors have been given at some point in their writing career. But what does it actually mean? On the surface it suggests that if you would like to read the book you wrote, then others would too, but that is a very subjective thing. I like historical fiction, but not everyone does. OK, we could narrow that definition down to something a little bit more specific then: Write the historical fiction book that you would want to read. Actually, that wouldn’t work for me. Because, while I enjoy reading historical fiction, I’m not so keen on writing it.  The main reason is all the research that is necessary for writing historical fiction. Readers of that genre usually know quite a bit about the period they follow and it only needs a small mistake for them to take the author to task. I know, because I’m one of the first to send emails to authors pointing out the errors they make. Research, however, is very time consuming and I’d much rather be getting on with doing the writing. I do research when I have to; most authors do. But I don’t want the research to take longer than writing the book and that is often the case with historical fiction. But the upshot is that while I really enjoy reading historical fiction, I don’t think ‘ll be writing too much of it. Well, that was a short blog wasn’t it?  Actually, I haven’t made my point yet. Because the book that I want to read is one that engages me and makes me want to read more of the same, regardless of genre. And I find that I get sent far too few of those. What that tells me is that some authors aren’t really writing for the benefit of their readers, they’re writing for their own benefit. Which means, as a publisher, I’m going to have a hard job selling their book. I’m not saying the books are actually bad, as such. Good and bad are subjective terms, after all. But what I am saying is that if I’m not engaged, I’m not enjoying the book and if I’m not enjoying it, I’m not going to finish it. And if I don’t finish it, then I’m not going to read anything else by the same author. Which is not good if the author wants to make a living from their work. And that's not good for me as a publisher, because I can't make a profit from publishing an author whose books don't sell. So, why am I not engaged with these books?  sketchy character sketchy character It comes down to the characters. They are usually too sketchy for me to take any interest in them. They have no depth, no substance. I can’t believe in them as real people. And if I can’t believe in them, I don’t care too much whether they live or die, or whether they live happily ever after or whatever is supposed to happen to them. So I close the book (or switch off my Kindle) and I look for something more interesting to read which does allow me to engage with the characters. This is mainly the problem with plot led novels.  plot led novels plot led novels The author has spent so much time creating what they think is an exciting or intriguing plot, and not enough time developing characters that I can care about. Because, even if the character is suspended over a fiery pit with the rope about to burn through and send him (or her) plummeting to their death, I don’t care enough about them to find out if they live or die. Let me give you an example. I care about my friends. Why? They aren’t relations so we don’t share DNA which needs to be passed to future generations, they don’t have any connection to me that makes any difference to my life. So why do I care whether my friends live or die?  Because I have engaged with them at an emotional level. I know their family history. I know how they got the scar on their elbow when they were 7 years old. I know how they nearly died in a car crash when they were 11. I know how they feel about their family, their spouse and their pets. I know that if I’m in trouble they will come and help me if they can and even if they can’t help, they’ll offer their emotional support. I know when they are feeling happy and I know when they are feeling sad, even though they may be trying to appear happy. I know what jokes I can tell that will make them laugh and they know the same about me. I know how to make them happy and how I could make them sad if I’m not careful; and they know the same about me.  And that’s how I want to know my characters: with that degree of detail. And far too many authors don’t let me feel that. They’ll provide a back story, because they know that is important, but the back story itself is too shallow: where the character was born, what sort of schooling they had; what they work at and maybe what sort of leisure activities they enjoy. But that isn’t ‘knowing’ them. To know someone you have to be able to see inside their head. Perhaps authors feel that if they reveal too much about a character then they will reveal too much about themselves. After all, many readers believe that characters in books resemble the author in some way. If that is the way the author feels, then they are in the wrong job, because writing is about baring your soul to the world. Because it is emotions that people actually engage with. We feed off the emotions of others the way a vampire feeds off the blood of their victims. We do that in real life (but not as vampires I hope) and we want to do it when we read books. But if the characters don’t have any emotional depth, then we can’t feed off them.  So, my point is that if you want to write the sort of book that you want to read, you have to be able to write about emotions, because that is what people actually engage with. The reader has to be able to feel a character’s happiness, their fear, their hopes, their dreams and their aspirations. So, my advice to any author would be to Google a list of human emotions and make sure your characters feel a selection of them. That way the reader will feel them and they’ll engage with the characters; they’ll care about them. And once they care about the characters, there is no way the reader will be able to put the book down before they have finished and, when they have finished, they’ll be begging the author for more. So, to re-phrase my opening statement: write the emotionally engaging character led book that you want to read. Not so snappy, I know – but more meaningful. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, why not make sure you don't miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. Just click the button below. We promise not to spam you and you can unsubscribe at any time.

0 Comments

The book reviews published here are the opinions of the reviewers and not necessarily those of Selfishgenie Publishing.  I came across this book, "Funny You Should Ask", by a rather unusual route, because it came out of a radio programme. Perhaps I had better explain. When I’m driving my car to the golf course to play golf on a Wednesday morning, I listen to the Zoe Ball show on BBC Radio 2. On that day each week she has a ten-minute feature in which the QI Elves are asked questions by members of the public and the Elves try to answer them. Perhaps a bit more explanation for those who don’t know what QI is, or a QI Elf for that matter.  QI is a panel show on BBC 2 TV in which the panellists try to come up with interesting (and possibly humorous) answers to various questions on a wide range of topics. Many of the answers given by the panellists turn out to be incorrect because we have been so badly taught over the years, having been given simplistic answers to complex questions. Some of the answers are wrong because our understanding of the world (and science) has advanced so much since we went to school (which was a very long time ago in my case). Panellists score points if they can come up with the “interesting” (ie correct) answers rather than the obvious and usually incorrect ones. Comedian Alan Davis is the only permanent member of the panel and he usually has the highest negative score (points are deducted for the wrong answers). His main role on the show is to play the fool, which he does quite convincingly.  Some of the QI Elves Some of the QI Elves Anyway, the people on the programme who set the questions and research the answers are referred to as the QI Elves and on Wednesday mornings some of them can be heard answering questions on Radio 2. From those questions has come this book, featuring the best of the questions and their answers. It isn’t the first book to emerge from the TV show format, there are at least 7 Others based on the TV show alone. But I haven’t read those and I have read this. A lot of the questions have been asked by children, but that is a good thing, because children ask some of the best and most challenging questions, as any parent can tell you.  I’m not going to go into detail on a whole load of questions, but here are a few examples:

Now, finding out the answers to most of the questions isn’t going to change your life very much, but a lot of the answers did make me say “Wow, I never knew that.” And, at my age, there’s not a lot of things that can make me say that. At the very least it will give you some subjects on which to amaze/bore your friends with now that the pubs are open again and Covid-19 is starting to wear a bit thin as a conversation topic.  One of the great things about this book is that you don’t have to read it from cover to cover. It’s great to dip into when you take a fancy to it. The answers are also quite short, so it’s a great book for reading if you are liable to be interrupted from time to time – such as during the daily commute (or by your children asking awkward questions). Because so many of the questions have been asked by children, the answers have to be presented in language that children can understand – which is also great for adults. There isn’t a huge amount of jargon used and where it is used, it is explained. That makes the book very readable. If you want the full scientific answers, then I’m sure you have the necessary knowledge on how to do the research. Why only 4 stars? Well, let’s face it, it’s hardly War And Peace. It is interesting and entertaining though. I am happy to recommend “Funny You Should Ask” to all lovers of trivia and for those, like me, who went to school so long ago that we were taught the world was round, when its actually an oblate spheroid. And if you really want to know where baby kangaroos go to the toilet – this book is definitely for you. To find out more about the book, click on the cover image  But the QI Elves aren’t the only people who answer questions. One of our authors does it too. Yes, he’s written three books (with a fourth in the pipeline) that answer the questions that you never knew you wanted to ask. His are aimed at more of an adult audience, but that doesn’t make them any less readable or informative. So, If you want to find out more about this series of books, titled “I’m So Glad You Asked Me That”, then go to the “Books” tab of this website and scroll down to the non-fiction works. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it helpful, make sure you don't miss an issue by signing up for our newsletter. Just click on the button below. We promise not to spam you and you can unsubscribe at any time. Would you like to be a guest reviewer for the Selfishgenie Publishing blog? Contact us with details of the book you'd like to review. Just three rules:

A recurring theme amongst new writers is “How do you start a story?”. For some people this is no problem. An idea pops into their head, they sit down at the place they do their writing and off they go. 80 to 100 thousand words later they have the first draft of their book completed. But for others it doesn’t work that way. For others, getting started is the difficult bit. Sometimes they have an idea in their head, but sometimes they don’t. They just want to write, but how do they get going?  Which is what this week’s blog is about. How to start your writing when you haven’t had that spark of inspiration to set you on your way. Even I need somewhere to start, so I’m going to start with “prompt phrases”. This is simply taking a few words that already exist and then continuing on from where they leave off. I’ll give you an example. “The door opened and …” continue writing from there. Where the writer goes from there is entirely up to them. It may end up as a short paragraph that leads nowhere, or it may end up on the shortlist for the Booker prize. Who knows? But great work always has a starting point and that could be it.  So, here are a few more prompts for you to think about.

It may be that by the time you stop writing, you will actually be able to remove those prompt words and you will still be left with something that stands up on its own. The great thing is that you can use the same prompts over and over again, just continuing with a slightly different set of words to create something entirely new. You can even create your own prompts or take the opening words from favourite books and use those to inspire your own work.  “Call me Ishmael” may have started Moby Dick, but it didn’t have to. There could have been a million different stories that emanated from those three words. And, providing you remove “Call me Ismael” from the starting sentence, no one will ever know you used it. If you search “writing prompts” on the internet you will come up with hundreds of articles with thousands more suggestions, some of which may be better than mine. The point about those prompts isn’t that they will lead the writer directly to a story. But they may give the writer a character, a location, a time, an incident or something else that then takes the writer to a story. It’s a bit like wanting to get to a certain street, but you don’t know where that street is. So you stop someone and ask for directions, or you go into a shop to do the same. That then gets you to the street where you want to be. The prompt phrase is the person you ask for directions. (For younger readers, people used to do that before we all had phones with maps on).  Then there is the “I remember” technique. Write the words “I remember” then follow it with three sentences. For example: I remember I went to the pub last week. Harry was there. We talked about football for a long time.” At the end of that you can remove “I remember” and you’ll be left with “I went to the pub last week. Harry was there” etc. Where you then take that is where the story will lead you. It may not lead anywhere, and you may abandon it. But there are many exciting and unexpected possibilities that can emerge from a trip to the pub.  One writer I know gets his inspiration from his favourite songs. He uses them to tap into his memories and emotions and they then give him a starting point for a story. Pick out a favourite song and listen to it. But while you are listening, ask yourself some questions and jot the answers down.

You might want to listen to the song several times to get more answers or to trigger fresh memories or additional questions. Once you have that, you can start to assemble the words into sentences. Some words you may use several times and some you may not use at all. They’re your words: do with them what you please. But when you’ve written those sentences, don’t stop. Keep writing, perhaps taking one sentence and writing a second, related sentence, much as you did with the “I remember” technique discussed above.  You can do that with other media as well. A painting, a sculpture, a book, a poem, a TV show, a film, or a play. All of them have etched themselves into your memory for a reason and those reasons can be your source of inspiration. Photographs, like music, are another good source of inspiration. We all have favourite photos, but you might want to dig out your albums and start looking at the ones you took years ago. Or, for our younger readers, access your cloud storage to find your old photos. Use the same techniques as suggested for listening to music.  Then there’s TV, radio or your news feed on the internet. The basic idea is the same for all three. Turn on your TV or radio or select your news feed on the internet (you might also use social media channels). Make a note of the first thing you see, hear or read. Don’t go searching for ones that may be more interesting. That becomes artificial and removes the spontaneity that is crucial for creativity. It doesn’t matter what it is. It could be a news story, it could be an advert, it could be someone discussing buying a house or selling an antique. Just write it down. Then, using the techniques discussed earlier, elaborate on what you have written. Try to reach around 500 words before you stop. Then imagine a character who is involved in whatever you have written and start to describe them. Some of things you might want to include are:

Combining the first 500 words with the character description should allow you to build even more. For example, the first character may have friends, an enemy, a lover, a helper and so on. How do these characters know each other? How did they meet? How is each one connected to the original 500 words?  Sheldon Cooper (actor Jim Parsons) Sheldon Cooper (actor Jim Parsons) The final suggestion I have for getting started with your writing is the “what if” question. Viewers of “The Big Bang Theory” may remember the episode in which the character of Sheldon Cooper imagines what The Hulk would be like if he was made for different materials, eg what if The Hulk was made of sponge? This is the same sort of thing. So, what if the old lady I saw on the bus yesterday is actually a serial poisoner?” So, you start writing “I saw an old lady on the bus today. She looked so sweet and innocent, but she had a deadly secret.  To change it into a third person narrative the sentence is started with “The old lady was sitting on a bus. She looked so sweet and innocent ….” So, here are some more “what if” ideas for you to play around with.

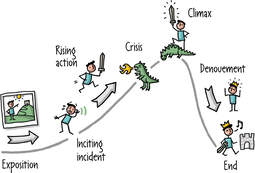

If you have particular interests or concerns (poverty, social justice, climate change, animal welfare, health, wealth etc), they could be turned into some excellent “what ifs”. There are pretty much an infinite number of “what ifs” that it’s possible to come up with. Spend some time generating a few (without answering the questions) then pick out just one to focus on and start writing. You never know where it might lead you.  Turning what you have written into a story is just a matter of technique. Short story writer E M Forster describes a story as “‘a narrative of events arranged in their time-sequence’ and a plot as "also a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality." To put that into context “The puppy whined piteously.” is a story. “The puppy whined piteously because it was hungry” is a plot. Turning that simple line about the puppy into a longer plot is matter of asking some questions and then answering them, but again focusing on causality.

Try to think of as many questions as you can. You may not answer them all, but the more you have the greater the possible plot permutations can have. None of the ideas discussed here are a universal panacea. Whatever you start out with may not lead anywhere. But it doesn’t have to lead anywhere every time. All it needs to do is get you writing.  Imagination is critical Imagination is critical Hold onto whatever you have created (I still have a box file from the days when I still used pen and paper) and go back and revisit these jottings from time to time. Perhaps they’ll provide fresh inspiration. But, importantly, just because one prompt didn’t lead anywhere, it doesn’t mean that the next one won’t. Ultimately writing is about imagination and these prompts are designed to stimulate your imagination. The rest is down to perseverance. And if you have neither an imagination nor perseverance, you aren’t a writer. You may be thinking “That’s all fine, but this is all about the here and now. I write fantasy/sci-fi/horror/westerns etc and those prompts don’t help me. Wrong. There is nothing that those prompts produce that can’t be transposed into any genre. Those genres are just a set of tropes that tell the reader what sort of book they are reading. The rest of it can exist in any time period or location – real or imagined. To think otherwise is to reveal a lack of imagination.  To use the example of the puppy, discussed above, it could live in Middle Earth, on the planet Gargelfarch or in a Native American tipi in 1879. It doesn’t even have to be the young produced by a dog. It could be a baby that has turned into a werewolf puppy and it’s howling because it can’t get out of its cradle to find a leg on which to chew. (Editor’s note: That idea is now copyright, Selfishgenie Publishing 2021). All writing should be fun and fun comes from playing. Anyone who has ever studied the processes involved in creativity and innovation will know that “play” is a big part of it. What this blog is about, really, is playing with words. It serves two purposes. The first is you learn by doing it. The second is that the ideas generated through this sort of play can be turned into something useable. It won’t happen every time, but it will happen. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative you may like to sign-up to our newsletter. Just click the button below.  One of the most asked questions of authors (after the most stupid question in the world - “Have I read anything by you?”) is “Where do you get your ideas from?” Some authors, especially those who write about the field in which they work, such as crime or medical, have an easy answer to that. They’ve either seen it or done it and are just winding it into their plot for the entertainment of their readers. But some authors base their fiction on their own real-life experiences outside of their profession. After all, most of us have fallen in love, been on a journey or had a traumatic experience, so all we are doing is turning it into fiction and perhaps adding a bit more pizzaz to it. For many, however, it is a slightly harder question to answer.  Brainstorm or mind map ideas Brainstorm or mind map ideas “It just popped into my head.” Sounds a bit lame, but that is really what happens for them. Other authors take a more structured approach and maybe do a bit of brain storming, writing words onto post-it notes and sticking them on the wall to see what jumps out at them. Or using writing prompts to get them going, which (spoiler alert) I’ll be covering in another blog next week. Others may watch TV or a film, or perhaps read a book and then think “That was pretty good, but it would have been so much better if the author had …” and then they write the same book their way. That isn’t plagiarism, by the way. At worst it is inspired imitation. There are several books I’d re-write differently if I had the time and if I do it well you probably wouldn’t recognise the original.  Visualise your idea. Visualise your idea. Some authors like to visualise things before they write them. For example, you might draw a picture of a house. You might then think about who lives in a house like that. Then you might think what could happen to those people that would upset their lives. Before you know it, you have both characters and a plot. I read about one quite well-known author (I’m sorry but I can’t remember his name) who drew each location he included in his plot so that he could get a “feel” for it. It also helped him to know where everything was in relation to other parts of the story. Others take their inspiration from life and use things they’ve heard or seen at work, in the street, at parties or wherever and then bulk them out until they become fully fledged stories. As an author I have used that latter approach. The fact is, no matter what method you use to start the story, the important thing is that it holds together as a plot and the characters are believable.  One of our authors came across some tape recordings his father had made for The National Army Museum, which recounted his experiences in the Army. It was for a project the museum was running at the time to capture the memories of old soldiers before they died and the stories were lost forever. He listened to his father’s voice and his first thought was to turn those stories into a book about his father, a mini-biography if you like. To do that he had to do a considerable amount of research about the commandos, their tactics and their battles so he could provide readers with the necessary background information to support and elaborate on his father’s words. But at the end of the process, when the book had been published (“A Commando’s Story” if you want to read it), the author realised he had all the material necessary to support an entire series of fictional stories set around the commandos of World War II. And so, the Carter’s Commandos series was born. One real-life story, told as an act of love and respect, turned into three years of work and six books (and still counting). "we all take inspiration from the work of others" There’s no doubt that we all take inspiration from the work of others. When it comes to sci-fi and fantasy, for example, there is little in real life that can provide the basis for a plot. Actually, that isn’t correct. Pretty much any story can be transferred into a mythical land or outer space or a dystopian future. It just requires the imagination to do it and that’s what most authors are good at: having a vivid imagination. It is said that there are only seven basic plots. All the author does to vary that is to change the context in which the story is set and add the characters. This idea was put forward by author and journalist Christopher Booker in his 2004 book, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. He was also a co-founder of the satirical magazine Private Eye. So, what are those plots?  Overcoming a monster. Overcoming a monster. The first is overcoming a monster. That is the basis for a lot of horror, of course, but also a lot of fantasy and sci-fi. Also, within the sci-fi genre, overcoming a monster might include combatting a plague of some sort. Fans of Michael Chrichton will be familiar with the concept. However, it is often used by action-adventure novelists. James Bond has to overcome many monsters in his various adventures. It’s just that the monsters have names like Goldfinger, Blofeld, SMERSH or SPECTRE. The monster to be overcome can be any enemy, though they usually transcend just being “bad” to being completely evil. Peter Benchley's "Jaws" is also a story about overcoming a monster. Rags to riches. This was a popular theme during the Victorian era, with authors such as Dickens (it’s the basic plot for Oliver Twist) and also the fairy stories Cinderella and Aladdin), but it is still seen today, but more often in film. Brewster’s Millions, The Million Pound (or Dollar) Bank Note are typical, but there are many others. An important plot point in the rags to riches story is that the protagonist comes close to losing, or actually loses, their newfound wealth at some point and has to overcome adversity to gain it back.  The quest The quest The quest. This is popular with fantasy novelists, but in sci-fi it is seen in the theme of space exploration and even historical fiction (Treasure Island is a quest). The Star Trek series is a typical quest, but sometimes also has to overcome a monster. Sometimes the quest takes a more abstract form. Jane Austen wrote a quest novel. After all, isn’t Elizabeth Bennet, in looking for a husband in Pride and Prejudice, embarking on a quest? Criminal investigations tend to use a lot of questing in order to identify the criminal(s), as does sci-fi that is seeking an antidote for a plague or a cure for a disease. Voyage and return. Well, if that isn’t The Hobbit, what is? It’s also Gulliver’s Travels and a whole lot more. The important thing about this plot and, also, the quest is that the protagonist learns something important along the way, usually about themselves. Bilbo Baggins, for example, finds out he is much braver and more resourceful than he thought.  Comedy. Pretty much any of the above plots can also be turned into a comedy, so I don’t fully buy it as a “plot” in its own right. However, if you set out to write a comedy it is important to be able to convey the humour. Far too many books we’ve read that are billed as comedies just aren’t funny. More than one commentator has said that Shakespeare’s comedies are less than funny. But maybe 16th and 17th century audiences understood the jokes better. Tragedy. The same applies to tragedy as it does for comedy, really. Any of the above plots can be turned into a tragedy by killing off either the protagonist, the protagonist’s love interest (if there is one) or their family. Hubris forms a great plot point in tragedy as it brings people down to earth with a bump. Pride cometh before a fall; how the mighty are fallen (and all that)! A book by Christopher Moore, called “Fool” turns the tragedy of King Lear into a comedy quite successfully, thus spinning the plot on its head  Like a phoenix from the flames Like a phoenix from the flames Rebirth. An interesting one this, because it isn’t a physical rebirth, it is usually a metaphorical one, though Frankenstein could be seen as a story of rebirth in a more literal sense. Like the quest and the voyage and return, it is about the character learning something and changing along the way, preferably for the better. However, a critical part of the rebirth plot is that the protagonist is either taken to the brink of death by their experience, or to the depths of despair. Only from those depths can rebirth take place. Much of religious fiction is about rebirth, as are stories that include battles with alcohol or drug addiction and battles with mental health. It is another important plot point that the protagonist, once reborn, is stronger in some way and not necessarily in physical terms. Of course, any two, or even three of those plots can be combined to create a single plot and this happens a lot in literature. So, seven basic plots, but millions of books that use those same seven. You wouldn’t think it possible, would you? "some people don’t agree with that concept " Of course, some people don’t agree with that concept and it has been much debated in the corridors of literary academia. There have been some authorities that have claimed both lower and higher figures. But all agree that the number of basic plots is finite and, more importantly, it’s quite a low number. There is also another rule in this plotting guide that not many people know they are using, but they use it anyway. It’s the rule of three.  So, it’s the third in a series of events that proves to be the decisive one. The third battle that wins the war, the third attempt at romance that leads to happy ever after, etc. This is most literally seen in fairy stories such as Goldilocks, where it is the third of the things that she tries in the three bears’ house that’s the one that’s just right. But the same principle applies in many different plots. For example, it takes three attempts (two failed or only partially successful) for the protagonist to achieve their ultimate goal. Or three events are cumulative in order to provide a final outcome. This is common in detective literature, where the significance of different clues add together to identify the criminal. The criminal isn’t just a left handed man, he is a left handed man who limps and also wears a monocle. Are you someone who uses the rule of three without realising that you were actually obeying a rule? Of course, you don’t have to obey that rule, but it is surprising how many authors do adhere to these conventions.  I don’t think many authors pay conscious attention to which of the seven plots they are using when they write their books. It doesn’t actually need a conscious decision. The plot may even start off using one of the plots structures and change direction later. For example, a quest might turn into a voyage and return or a rebirth. A plot may start off being a comedy but become tragic along the way and it may even return to being a comedy by the end. What is important, however, is that whatever plot(s) you use, they tell the story the way you wanted to tell it, whether it was inspired by something heard at a bus stop or by the life story of a relative, or even as a consequence of personal experience. Enjoy your writing, but don’t over-think it. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, why not make sure you don't miss future editions, by signing up to our newsletter. For example, we'll send you a reminder about the one we're publishing next week relating to the use of writing prompts to generate story ideas. Just click the button below. |

AuthorThis blog is compiled and curated by the Selfishgenie publishing team. Archives

June 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed