Is the game up for traditional publishers? I’m not talking about today or tomorrow. What I’m talking about may take years to come to fruition, but the publishing world is changing, and the trad publishers don’t seem to have cottoned on to the fact yet. Between themselves and agents, they have made it almost impossible to access mainstream publishing. The gate keepers are no longer just keeping the gate, they are building high walls and digging moats so deep in front of the gate that no one can get in.  Which is why not only is the publishing model changing shape, it has no choice but to change shape. But the trad publishers are sticking their fingers in their ears and singing “la, la, la”. With so many authors now taking the self-publishing route, it is becoming the norm rather than the exception. According to this article, 300 million self-published books are sold each year. That’s 30-35% of the publishing market. While the global publishing market is expected to grow by 1% per year, the self-publishing market is expected to grow by 17% per year.  Prior to 1998, the only way to self-publish was to pay a printer to print your books, then hawk them around local book shops trying to find one to stock it for you. But in 1998 Chip Wilson, a millionaire entrepreneur, created a self-publishing website called Lulu and that all changed. Now anyone could publish their book on-line and sell it through the platform. Imitators followed and, of course, the retail giant Amazon established their own platform, Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), which now dominates the self-publishing market. So, from almost nowhere in 1998, self-publishing now holds approximately 34% of the market – and growing. I’m not going to say that the quality of the books is 100% great, but there are plenty of good self-published authors and many make a respectable living from their writing. In fact, some make a better living than authors who are trad published. There are at least 7 self-published authors achieving 7 digit income levels and many more making 6 digit levels.  Which is one of the reasons I think there will be further shifts in the industry. A trad published author receives about 10% of the sale price of their book in royalties. From that they then have to pay their agent (actually the agent usually gets the royalty cheque, deducts their commission and then passes the rest to the author). Richard Osman’s latest best-seller is priced at £11.99 for the Kindle edition and £9.99 for the paperback at the time of writing this blog. Don’t ask me why the paperback is cheaper because I don’t know, but it probably started out being more expensive. Based on current publishing practice Richard will receive around £1.19 in royalties for the Kindle edition and around 99p for each paperback sale. If he were to self-publish and sell his book at the same price, he would make either £3.60 or £8.39 per copy, depending on whether he took the 30% or 70% royalty option. If I were Richard, I’d be starting to wonder about the wisdom of sticking with trad publishing.  As a big name author, he would have no problem setting up distribution deals with all the major retailers, without having to rely on his publisher to do that for him. The rest is down to editing, cover design and marketing and he could hire people to do that for him. I think he’d still end up with more money in his pocket than he does now. For a start, he wouldn’t have to give between 10% and 20% of his royalties to an agent. I suspect that a lot of trad published authors will do these sort of sums in future and when their existing publishing deals come to an end, they’ll self-publish the next book they write.  It is noticeable that publishers are now trying to tie authors into multi-book contracts in order to prevent that sort of desertion, though at the moment they are more worried about their authors being poached by other trad publishers than they are about their authors opting to self-publish. The more top quality authors who go down the self-publishing route, the better the reputation self-publishing will gain. I strongly suspect that the much of prejudice against self-published authors is being fuelled by trad publishers trying to protect their businesses.  Change sometimes happen at a glacial speed. But change can also function more like a snowball rolling down a hill, getting bigger and bigger and going faster and faster. I may not be around for long enough to see which metaphor is more accurate, but many of you will be. But I predict that one day, when a new author announces on social media that they are about to start querying their novel, the response from other writers won’t be “Good luck”, it will be “Why on Earth are you bothering with that?" If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.

0 Comments

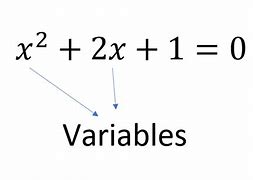

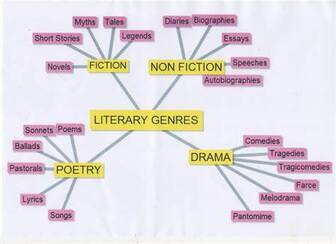

Disclaimer: No financial inducement was offered or requested for this review and no payment was received. The reviewer was provided with a free review copy of the book. The views expressed in this review are those of the reviewer and are not necessarily those of Selfishgenie Publishing.  Exiles, by Miles Watson, is a novella, but it could almost stand as a full length novel. The book serves as an introduction to “The Magnus Chronicles”, a series of dystopian novels set in a world that could be Earth in either the past or future. That is not clear from the story. Is it an alternative history or a possible future? I think the reader must decide. There is some modern technology, but it is limited by “The Order”, the body that rules over most of Europe. However, there is also a lot of 19th century technology still in use, though that might be because so much modern technology is banned. This little book actually tells two stories in one. The first is told by Marguerite Bain, the Captain of a smuggling ship. Smuggling is an organised, if dangerous, profession with its own ruling Guild. Marguerite gained her command under the tutelage of a senior Captain who now serves as one of the Guild’s governors. While smuggling is illegal, a blind eye is turned for the most part. Bribery and corruption play a large part in that unofficial tolerance, as it does in most of life under The Order. Marguerite has had a hard life, not one to be envied by any woman. Now, as skipper of her own ship, she has to show that she is ready to kill anyone who challenges her position and the only way she has been able to prove that is to do it. Now an uneasy truce lies between her and her crew, though she knows that if she shows any sign of weakness they would kill her, after taking their pleasure first, of course. The Sea Dragon, her ship, is contracted to deliver supplies to the eponymous exile on his remote and barren island. It is a task she is unable to refuse because it has been brokered by the Guild and such a contract can’t be broken. Her orders are strict. Deliver the supplies and leave the island. Do not make any attempt to communicate with the exile. The previous contractor forgot those rules and now he is no longer alive. But Marguerite is curious and can’t resist finding out about the exile, so she secretes a notebook and pencil in the supplies, asking him to tell his story. Which is the second story in the book. Enitan Champoleon is a name that is notorious as an opponent of The Order, an organiser of the resistance. He is almost mythical, a sort of Scarlet Pimpernel figure. But if the Order captured him they would just kill him, not exile him on a barren rock. So, who has placed Champoleon in this living hell? All becomes clear by the end of the story. But through this dialogue Marguerite starts to feel a bizarre kinship with the exile. The story's point of view switches back and forth between Marguerite and Enitan but at all times it is clear who is narrating. The style of language is fitting for the ambivalent chronological setting of the book. In many ways it is Victorian, but interspersed with more modern phrases and idiom. Either of the two stories are capable of engaging the reader fully, but the two of them together become compelling and the book is a real page turner. For lovers of fantasy or sci-fi it is a very good read. This reviewer is now a convert and will soon be embarking on reading The Magnus Chronicles in full. The ebook can be purchased from Amazon for £3.95 or can be downloaded on KindleUnlimited for free. The paperback version is £4.74 (all prices correct at time of posting). I recommend “Exiles” by Miles Watson and to find out more, click here If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  People talk a lot about the law of averages. By this they mean that if they do something enough times, there must be enough positive outcomes to balance out all the negative outcomes, to restore an average outcome at some imaginary point. This is a fallacy. It is also flawed thinking. Except in purely mathematical terms, there is no “law of averages”. For some things there are only ever negative outcomes or positive outcomes. There is no celestial balancing act between the two. The sheer number of variables in so many of life’s occurrences mean that no “average” could ever be achieved, because each one is essentially unique. People confuse the laws of statistical probability with the law of averages.  Statistical probability relies on things not changing between one occurrence and the next. If you toss a coin 100 times, for example, it should come down heads 50 times and tails 50 times. The amount of force used varies from coin toss to coin toss but, statistically there are only two possible outcomes, so the probability of one outcome vs the other is 50:50. But in most of life's occurrences, there are too many variables for statistical probability to give you a 50:50 outcome. In any occurrence the number of variables is sometimes so great that the number of possible outcomes is mind bogglingly large and there is no guarantee that any of those outcomes is going to be a positive one.  Gamblers work on a different fallacy with regard to "the law of averages". They believe that if something hasn’t happened for a while, (like the little white ball landing on certain number on a roulette wheel), then, by the “law of averages” it must happen very soon. However, where the ball lands on a roulette wheel is random (if the wheel isn’t rigged). The ball can just as easily land on the same number twice in succession as it can land on a number that it hasn’t landed on in a while. The ball hasn’t any will, so it can’t choose where it lands. The ball also has no memory, so it doesn’t know where it has landed and where it hasn’t (the same applies to lottery numbers). But the speed of the wheel, the way the croupier places the ball onto the wheel, and the point at which it is placed, are all variable, making each turn of the wheel unique.  Similarly, if a racehorse hasn’t won a race in a while, there is no reason to suppose it will win its next race. It isn’t winning races because it isn’t as fast as the other horses. It is not suddenly going to get faster, nor are the other horses suddenly going to get slower, just to satisfy some non-existent “law of averages”. A change of jockey or a change in trainer may result in the horse winning a race, but that has nothing to do with the “law of averages” because something has changed, therefore changing the likelihood of the outcome. It is the change that made the difference. Let me give you an extreme example. If you stick your hand in a fire, it will get burnt. That is a negative outcome. But there is no positive outcome. You cannot ask 100 people to stick their hand in a fire and get a negative outcome in the belief that the 101st person to do it won't get their hand burnt in order to satisfy the “law of averages”. I’ll give you another example, this time less extreme.  If a job applicant sends out their CV (resumé for our American readers) to 100 companies and gets no response, sending it out to another 100 companies does not mean that there will be a company that will decide to take a chance on the applicant, just so the “law of averages” can be balanced out by a good outcome. If a CV has been rejected 100 times, there must be something wrong with it because 100 companies are not going to reject a good candidate for a job. And so we get to the nub of this week’s blog.  When it comes to querying a book, there is also no law of averages. OK, not every agent that the MS is sent to will be the right agent for that book. A bit of research can eliminate those before the query is even sent. Also, some agents may not really be looking for new authors, so they will reject the MS and other agents may not read the submission properly and so will reject it because they didn’t “get it”. There may be other reasons why some agents reject an MS which have nothing to do with their literary merits. Who knows? But sending a query out time after time and getting the same result doesn’t mean that the law of averages says that on the next attempt you will hit the target with the right agent. If you get past a certain (unspecified) number of rejections, then it probably means that no one likes your MS and the time has come to stop sending out queries and start reviewing your MS to find out what is wrong with it. or to review your options for getting your book published. Or both. In other words, it’s not them, it’s you (or, rather, it’s your MS).  We see a lot of posts on social media with people saying they’ve sent out their MS again to another hundred agents, or direct to publishers, and this time they’re hoping for better results. If you have made over 20 queries the chance of finding an agent is actually getting smaller, not bigger because there is no law of averages. There is only an MS that agents/publishers like or one that they don’t like enough to take a chance with. Don’t take that number of 20 as being some sort of empirical threshold. It just feels about right to us. Maybe it’s 25, maybe 30, but we doubt that it’s much higher. Einstein defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different outcomes each time. He knew there was no such thing as a “law of averages”. So, are you displaying that sign of insanity?  In the world self-publishing this maxim also applies. If you have tried the same things time after time to sell your book and sales haven’t improved, there is only one of two conclusions you can draw. Your approach to marketing is wrong, or the book isn’t attracting readers for some other reason. If the marketing you are doing isn’t selling your book, then you have to try something new. If you always do what you always did, you’ll always get what you always got. If you want something different you have to do something different. And if you have tried something different and the book still isn’t selling, you have to look at the book itself and ask why readers aren’t attracted to it. Maybe it’s the cover image. Maybe it’s the blurb. Maybe it’s the “look inside” sample, or maybe it’s the reviews that have been posted. Maybe it’s something else entirely. But the thing it won’t be is the law of averages. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  It is the dream of all Indie authors: to snag an agent or a publisher and get that elusive publishing deal. Yet so few Indie authors are able to fulfil that dream. But it is achievable, and it is probably easier than you think. However, it is also somewhat counterintuitive to do what is necessary to fulfil the dream. It may also require the author to make a few compromises. OK, if it’s that easy, tell us the secret, oh Selfishgenie. OK, we will.  The first thing you have to do is recognise that publishers hate taking risks with new authors. Risk threatens to reduce profits and there are stories in the industry of publishers being left with warehouses full of books because they took a gamble on a new author that didn’t pay off. These stories are probably apocryphal, but they are enough to give publishers nightmares. In that case how do new authors ever get signed? The answer to that is that it isn’t always the author themselves that represents the risk. It’s the type of book they are writing. The author may be the next Ernest Hemingway or Hilary Mantel in terms of the quality of their writing, but if they aren’t writing the sort of books that readers want to read, then they will never become bestselling authors. It is quite possible that in today’s market, Hemingway would also be unable to find a publisher because his type of books aren’t selling these days (my speculation, of course) Which is why new those authors represent a risk. This is where things become counterintuitive.  You may think that to get that elusive publishing deal your book has to be different from what is already out there in the bookstores. You would be wrong. It's the exact opposite. Your book has to be the same (or at least similar) to what is already out there. To de-risk their industry, publishers follow the reading fashions. If J R R Martin’s books are selling, then publishers are hungry for books just like his. If Lee Childs’ books are selling, then publishers will also be hungry for books like his. So, if you want to snag that elusive publishing deal, your books have to follow the fashion. By publishing books that are what the public is reading at that moment, publishers are able to de-risk their products Give the public what they want and they’ll come flocking to your door.  We already see this in cinema, of course. In the last decade, 5 of the top 10 box office hits were superhero movies, four of which were from the Avengers franchise and the 5th was Black Panther. Of the remaining 5 one was from the Star Wars franchise, another was from the Jurassic Park franchise and two more were Disney films, which are always popular. If that’s what the public wants, is it any surprise that we get so many superhero films, Star Wars films, Disney films et al? And the same applies to books. This desire to follow the fashion then feeds back to agents. If publishers want a particular type of book, then agents will want to find authors who are writing that type of book. Because it is easier, and more lucrative, to sign authors who are writing the sorts of books that publishers are looking for. So, sending an agent something different is not going to get you signed. Of course, going to Bloomsbury or Scholastic Press and offering them a Harry Potter clone isn’t going to help the Indie author. After all, those two publishers already have the original Harry Potter. No, you need to approach a publisher/agent that hasn’t got Harry Potter and offer them your clone.  At the same time as responding to fashion, publishers also create reading fashions. After all, if all the publishers are producing Harry Potter clones, then that limits the choice for readers, so they buy them even if they would actually welcome a change. We see this each year with clothing fashions. If manufacturers decide that green baseball caps are going to be “in” this year that is what they will produce, and they will pay “influencers” to get the public to wear them. Pretty soon all you will see will be green baseball caps! Then, next year, because everyone already has a green baseball cap, they’ll switch the colour and repeat the trick so they can sell more product. And we fall for it, so we only have ourselves to blame. Exactly the same methods apply with books. But you don’t want to write Harry Potter clones or Jack Reacher clones, do you?  You have your own story ideas and those are the ones you want to work on. You have “artistic integrity” and you won’t be dictated to with regard to your plots, your characters or your writing style. OK, I respect that. But artistic integrity doesn’t put food on the table. When you are a big name writer you have a bit of power that you can exert. Your name alone will sell books. That means your publisher is likely to be more flexible about what they will buy from you. And if they aren’t flexible, your name is big enough to open doors to other publishers who might allow you to write what you want, because you no longer represent a risk. You are “box office”, as they say in the movie making world.  It’s the reason why celebrities who can barely write their own names are able to get publishing deals. It’s not the quality of the book that sells it, it’s the name on the cover,. But you have to be a “name” first and that may mean compromise. Write what the publishers want now, so you are granted the freedom to write what you want to write in the future. So, what should you be writing right now in order to snag that contract? The answer to that is likely to change from month to month and year to year, which isn’t helpful. The best sellers list on Amazon will tell you what is fashionable right now as will the Sunday Times (or New York Times in the USA) best sellers list, but that won’t tell you what will be fashionable in 6 months’ time when your book is ready for querying. Fortunately, fashions in reading change quite slowly, certainly slower than they do in clothing, so you probably have time to get on the bandwagon with your next book. The top three genres (UK) to write in are Crime and Thrillers (33% of the market) , Fantasy Fiction (22%) and Action & Adventure (20%). There are, however, subdivisions below those headline genres and not all of them are as popular as others. But what you will probably notice is that the most popular books right now are character led, not plot led. Less popular at the moment are Modern Classics (No idea, but they are only 11% of the market), Horror (11%) and Short Stories (14%)* Some genres are so unpopular that their market share doesn’t even register on the graphs.  Some publishers do allow themselves to take a few risks. They look for good new writers and offer them publishing deals. However, they won’t throw a lot of money into marketing their book. At least, not the first one. The first print run of the hardback version of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was only 500 books, most of which went to libraries. That’s how much faith Bloomsbury had in J K Rowling for her first book. Fortunately it was the American market that saw its potential and made her the best-seller she is, while the UK market caught up later. So, yes, you might find an agent and a publisher willing to take a risk on you even if you aren’t writing whatever is fashionable. But it is probably going to be a harder furrow to plough. * Figures for 2020, the most recent we could find from a reliable source. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  It is disturbing to read on social media, especially Twitter, that so many authors struggle with writing a synopsis for their book. After all, they have just written between 80k and 140k of beautiful prose but are struggling to write just one page of A4 that will communicate to an agent or publisher what the book is about. Perhaps, like panic, the under confidence of some authors is spread to other authors like a virus, making perfectly confident writers suddenly doubt their ability. It is about the only explanation I can think of. But rather than try to analyse the cause perhaps, in this blog, I can help authors by offering some practical advice.  The starting point of any task is to establish a goal – something to aim for. Fortunately, agents and publishers have already done that for you, because they know what they want from a synopsis. To put it simply, they want to know what your book is about in as simple language as possible, so that they can be confident that the author knows what it is about. You may wonder about the last part of that sentence. After all, surely the author knows what their book is about, don’t they? Apparently not. The author may think they have written an exciting fantasy/sci-fi/hist fic/YA/whatever novel, but if they can’t explain that in simple terms, the agent (or publisher – I’ll stop using both terms from here) won’t believe that they know what they are doing. "Pick one genre!"  To start a synopsis, you must first clarify what genre it is written for. If you think your book crosses genre boundaries, eg a fantasy that includes a romance, then which genre is it mainly aimed at? In life I have often said that you don’t always have to pick a side, but in writing a synopsis you do have to. Pick one genre! If the romance element of the story is crucial to the fantasy plot, you can cover that later (or vice versa if romance is the main genre). And don’t start getting into sub-genres, the way Amazon categorises books – they have something like 16,000 different genre classifications. In reality there are between 35 and 50 recognised genres, depending on who you ask. Purists would argue that it is an even lower figure, but that is why they are called purists.  Picking your genre is vital because your agent has to know that the book has a chance of making money. Writing in an unfashionable or unpopular genre is going to dispatch your novel to the reject pile faster than a split infinitive ever would. Also, there are many agents who specialise in a specific genre and they want to know up-front that they are the right agent for your book. They won’t waste their time reading your book if it isn’t in their genre. The next step is to write a brief (75-100 word) summary of the plot. It is suggested if you can’t summarise the plot in that few words, then you don’t really know what you have written. To give you some idea of what I mean, try this summary of one of our author’s books.  “Operation Absolom tells the story of a young man, Steven Carter, who enlists in the British Army during World War II. Bored with garrison duties he decides to volunteer for a more adventurous life with the newly formed commandos. In doing so he gets far more adventure than he bargained for and comes close to losing his life in the freezing waters off the coast of Norway. In order to survive, he has to dig deep into reserves of courage and determination that he didn’t know he possessed.” To save you counting, that is 88 words. The key thing about that summary is that it tells you when the story is set (World War II), who the protagonist* is (Steven Carter), what he gets himself involved in (fighting in the commandos) and why he gets involved (seeking adventure). It also tells you that he gets more than he bargained for, which is the source of much of the drama in the plot. The last sentence indicates a degree of personal growth taking place during the story- which means that the character develops as the story goes along.. (FYI you can find out more about Operation Absolom by clicking on the cover image)  The main body of the synopsis is a longer description of 300 to 500 words. The way I go about that is to take each chapter in the book and write a single sentence saying what that chapter is about. Again, using Operation Absolom as an example, here’s what we came up with.

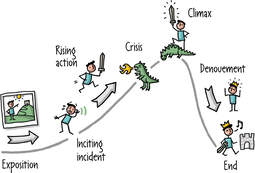

And so on. If there are chapters that just deal with sub-plots, delete those sentences. There is nothing wrong with having sub-plots, but the agent is more interested in the central plot, so confusing things with sub-plots and using up valuable word count along the way isn’t going to help your case. Now join the sentences up into sensible paragraphs, emphasising the major points of the story. If you are familiar with the way story arcs work, with highpoints preceded by build-up and followed by aftermath, then it is important that the description follows the same pattern, so that the agent can see where the high and low points are and therefore get some feel for the pace of the story. This is what we did with the three sample sentences we produced above: “After a conflict with his commanding officer, Steven Carter decides to volunteer for the commandos. His training in Scotland reveals an unconventional approach to soldering that risks cutting his commando career short, but he survives to join his new unit, 15 Commando. At once he is pitched into training for a top secret operation, Operation Absolom.” I’ve used only 57 words to cover almost a quarter of the book, leaving me plenty of word count still available to deal with the more action packed parts of the book. Note the hints and teasers used to tantalise the reader eg conflict, unconventional. If you are struggling to keep below the 500 word level, then you are probably including non-essential information.  As well as sub-plots, don’t include: - Dialogue, - Descriptive passages, - Inconsequential characters, - Backstory (you may hint at this with phrases such as “troubled past” or “difficult family life”), - Moralising messages - Metaphors (speak plainly). If you include any supporting characters, refer only briefly to their role in the plot and their relationship to the protagonist, eg Sam is Frodo’s best friend and would rather die than be left behind in the Shire. Later in the story he takes on greater significance in making sure that Frodo fulfils his purpose.  Beware the search for perfection! Beware the search for perfection! The final, short, paragraph just closes the synopsis off in a neat and tidy manner. Tell the agent what the total wordcount is and if you have any plans for a sequel. If the sequel is already underway, say that. If book is intended to be part of a series, say how many books you are planning for it (agents like to know they can expect a long term relationship with an author (with accompanying long term income)). Finally, beware of seeking perfection. You can spend a hundred hours on drafting and re-drafting 40 versions of a synopsis and it probably won’t be any better than the second or third draft. The agent doesn’t care if the synopsis isn’t perfect because, unlike the book, it isn’t something that is ever going to be published. The agent expects it to be properly spelt and grammatically sound, that is all. What they are really interested in is whether or not the story sounds interesting enough to read all the way through. How do you know if your synopsis is good enough? The same way as you know your book is good enough. Show it to someone whose opinion you value and ask “Would you read this book based on this synopsis?” As always, don’t rely on family or friends to be honest with you – they love you and tend to say what they think you want to hear. Use someone who can be relied upon to be impartial, such as your beta readers. If you haven’t got anyone to whom you can show your synopsis, send it to us. You can find our address on our “Contact” page. Make sure you tell us that you just want some feedback on it, so we know you aren’t submitting your book (though we may invite you to submit it if we like the sound of it). * Always use the word “protagonist” in a synopsis, not “main character” or “MC”. It is more professional sounding. There is only ever one protagonist. Anyone else is a “supporting character”. For the same reason the “villain” is always the “antagonist”. If you have enjoyed this blog and want to make sure you don’t miss future editions, you can sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so. Just click the button below.  You’ve written this great book, but you can’t seem to capture the interest of an agent or publisher. You’ve sent it to every agent and every publisher in the listings, but all you get back is rejections and sometimes not even that. How long does this go on for before you ask yourself “Is it me?” On the other hand, you may feel that your work isn’t good enough for publication, so you may not have submitted it to an agent or publisher because you think it will be rejected. Why might you feel that way? Let me introduce you to the Dunning-Kruger effect.  Stupid people don't know they are stupid! Stupid people don't know they are stupid! This is a hypothesis in social psychology postulating that people of lower capability don’t know their capabilities are low, while people of higher capability don’t always realise how capable they are. This has sometimes been unfairly paraphrased as “stupid people don’t know they are stupid” and, of course, the opposite of that is that clever people sometimes don’t realise how clever they are. I have to say up front that there are critics of the hypothesis. Firstly, in some cultures there is great emphasis placed on modesty, so a clever person would never claim to be cleverer than someone else, because that would be immodest. Similarly, in some cultures it is considered rude to criticize others, so honest feedback on poor performance isn’t always provided. The other flaw is that the studies that were carried out to test the hypothesis used psychology students as the subjects and they aren’t representative of society as a whole. But leaving aside those criticisms, there is consistently strong evidence that the Dunning -Kruger effect is real . But what do we know about it?  David Dunning and Justin Kruger are the two American psychologists that came up with the hypothesis (published in 1999) after noting that some of their poorer performing students didn’t seem to realise how poor their performances were. They also didn’t improve after being given feedback on their performance. So Dunning and Kruger went looking for an underlying cause for this misperception of capability. To test the hypothesis, subjects were asked to complete some self-assessment tests on a range of subjects. After being given their results, the students were asked to rank themselves against their peers. Those that performed the worst tended to rate themselves higher than some of their peers, while those that had performed the best tended to rate themselves lower than some of their peers.  Subjects were interviewed after completing the exercise and asked why they had rated themselves as they had. The more capable students, who found the tests easiest, tended to think that their peers would also find the tests easy, so they had ranked themselves lower. Conversely, the poorer performing students, who had found the tests difficult, assumed their peers would also find the tests difficult and ranked themselves higher. This betrayed an internal bias. Poor performing students overrated their own performance, while better performing students overrated the performances of their peers. Even after providing feedback, these internal biases appeared to persist.  At this point I should inject a word of caution. The poorest performing students didn’t rank themselves in the highest performing bracket. So, a D grade student didn’t think they were performing as well as an A grade student. But they did assume they were performing as well or better than a C grade student. So, what has this to do with finding an agent or a publisher? Well, if we extend the Dunning-Kruger hypothesis into the world of publishing, an author who isn’t a great writer may, thanks to this internal bias, think that their work is better than it is. This will make it hard for them to understand why they are getting rejection after rejection.  On the other hand, a good writer may feel that their work isn’t as good as that of other good writers and that may discourage them from submitting their work to an agent or publisher in the first place, because they assume it will be rejected. If that is the case, is there a solution for the writer? There may be. The first thing to do is to understand that a cognitive bias actually exists and recognise the effect it might be having on our own perception of ourselves. We need to actually ask if we are as good (or as poor) as we think we are. And the only way to answer that question is to seek out unbiased feedback.  Many of you will already have worked out that I’m talking about beta readers. Friends and family aren’t good beta readers, because they don’t want to hurt the author’s feelings. They would tell William McGonagall* that his poetry is great if he was a friend or relative. This means that if an author wants honest feedback on their work, the beta reader must be a stranger, so that they can provide feedback that is free of any bias caused by emotional involvement. But there is a trap here that many authors – and beta readers – aren’t aware of. While a beta reader may start off being an unbiased stranger, that relationship changes over time. Authors want the best feedback, so they will nurture a valued beta reader and use them again and again. But the beta reader is bound to have an emotional response to that nurturing and that may affect the nature of their feedback. In other words, they may develop an emotional bond with the author which could classify them as a friend, thereby losing the independent viewpoint that made them so valuable in the first place. You might think of it as the Catch-22 of beta reading. If you are starting to think of a beta reader as a friend, then they have lost their value, but not treating them as a friend risks losing them. Ideally an author will find new beta readers for each new work. But that means a lot of work identifying and cultivating them, only to have to do it all over again for the next book and the next.  Florence Foster Jenkins Florence Foster Jenkins But being aware that the trap exist in the first place is a good first step. Be aware that the beta reader may want you to like them almost as much as you want them to like your work. As soon as you have exchanged email addresses, an emotional bond is starting to form, so it is necessary for both authors and beta readers to try to maintain an “arm’s length” relationship. However, having independent feedback is no use if you don't respond to it. Your beta readers have given you feedback - use it to improve your work. If you ignore it because it isn't what you want to hear, you have fallen into another trap and the Dunning-Kruger effect even predicts that trap because it identified that subjects often didn't respond to feedback on their performance. Who knows, you may improve your work enough to find an agent or a publisher. * William McGonagall (1825-1902) was a Scottish poet whose poems were so bad that he became famous. People paid to see him read his poems for the comedy value (his work was quite serious in its subject matter). McGonagall, however, was deluded enough to interpret that as evidence of his genius. See also Florence Foster Jenkins. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, why not make sure you don't miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. Just click the button below. We promise not to spam you and you can unsubscribe at any time.  Have you submitted your book to agents or publishers and had it rejected? Have you ever asked yourself why your masterpiece was rejected? After all, you have read far worse books than yours, so why wasn’t your much better book accepted? Have you ever thought that it might be because you didn’t adhere to the submission guidelines? As publishers we receive a lot of submissions and one of the things that puzzles us the most is how someone who can write a 100,000 word novel can’t read a simple set of instructions.  You may wonder why adhering to the submission guidelines is so important. After all, it has nothing to do with the quality of your work. Your masterpiece will still be a masterpiece, even if you didn’t double space it, as the submission guidelines asked you to. We’ll answer that in this blog. Our submission guidelines are published on our “Contacts” page of this website. They are longer than they are for some agents or publishers. That’s because we’re trying to be helpful, so we tell authors in advance why we might not accept their masterpiece. That gives them the opportunity to take a look at what they have written and decide what sort of a chance they have of being accepted if they submit their work to us. We may not actually be the right publisher for them, so why waste everyone’s time?  But even if we are the right publisher, are they the right author? We have no way of knowing without setting them a little examination – but here’s the trick – we also provide the answers to the exam questions. And that makes it much harder for authors to fail. So why do so many authors send us into apoplectic fits of rage by not reading the answers? OK, I’m exaggerating for comic effect, but it is very frustrating when you open a submission and find, not the 10,000 words that were asked for in the guidelines, but the whole (expletive deleted) manuscript. And it's double line spaced when we asked for something else. I have actually emailed an author and asked him why he didn’t read our guidelines. He replied to say that he did read them. So I then asked him why, having read the guidelines, he had decided to ignore them. He replied that he didn’t think we were serious and they were just to discourage authors from making submissions. Yes, that’s right, we spend hours making things up just so we don’t have to read submissions. That’s how we stay in business, by not having any new material to publish. (sarcasm).  I didn’t use the word “examination” above by accident, by the way. So why did I use it? When you submit a book to an agent or publisher, it ceases to be “your book”. The act of submission turns your work into a collaborative project. Your name will still be the one on the cover of the book, but it won’t get to the bookshops without a lot of teamwork between you and the publisher. So, when you submit the book, the agent or publisher wants to know if you are the sort of person with whom it is going to be easy to collaborate. Trust us on this, but no author ever submits a book that is ready to go straight to press. They all require some degree of work to turn them from what they are into something that the readers will want to buy. The only difference between submissions by different authors is the amount of work needed to get from A to B.  The greatest authors ever to put words onto paper have gone through this process before you, so don’t think you are some sort of special case or genius who can go straight from submission to publication without stopping to do a few re-writes along the way. That’s where the publisher has to start spending money – without knowing if they will ever get any of it back. A publisher will pay an editor to work with you to make your book the best it can be, and that editor will earn between £20k and £40k per year. Freelance editors start at around £25 per hour, charging up to £54 per hour if more specialist services are needed. (comparable rates apply in other countries). That may well be more money than you, the author, will receive in royalties. So, the publisher (and the agent who will try to find you a publisher) wants to know if you are going to work with that editor, or work against them. Is it worth them spending £5k to £10k of an editor’s wages working on your book with you if you are going to ignore everything the editor suggests? "If you can’t be bothered to read the submission guidelines, are you really going to read the editor’s notes?"  Someone, I don’t know who, once said “You only get one chance to make a first impression.” Your submission is your only chance to make that first impression. What the agent or publisher sees when they open up your manuscript is when that first impression is made. If it is the right length and formatted the way the agent or publisher has requested it, they are going to start to think of the author in a positive way. If they asked for a synopsis but you didn’t provide one, then you probably didn’t read the guidelines, or you decided they didn’t apply to you. If they asked for a biography but you didn’t include one, they will wonder why you didn’t. If you haven’t done those things, the negative thoughts will start, which means the author’s work has to be so much better than the average before the agent or publisher starts to move across to having more positive thoughts.  So, we have devised an additional test for our authors. We don’t insist that authors use our formatting guidelines, we just suggest that if they want to impress us, they should use them (item 6 if you decide to read them for yourself). If the author responds to our suggestions, they get off to a good start with us. If they just submit the MS formatted the way they wrote it, then the start isn’t going to be such a good one. So, for your own good, if you are going to submit your work to an agent or publisher, please read and follow the submission guidelines because first impressions count for so much. After that, your writing talent will do the talking for you. Don’t get me wrong. The agent or publisher won’t make a final decision based on whether you have used the right line spacing or the right font. If the story is good enough it could be written on a brown paper bag with a blunt crayon and it will still be accepted. But if you want the agent or publisher to be on your side from the moment they receive your submission, you have to do what is necessary to get them there, by following the submission guidelines. And if you think following submission guidelines is for losers – good luck with your career in pizza deliveries. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative and you don't want to miss future editions, just click the button to sign up for our newsletter. Week 3 - Size Isn’t Everything  Last week we looked at trying to find yourself an agent. Of course, we hope you succeed in your search, but you may not. There may come a time when you have exhausted your list of agents compiled from “The Artists’ ℇ Writers’ Yearbook”, but that doesn’t mean you are at the end of the line. Oh no – you have hardly even left the station.

I said in last week’s blog that each submission was a one-shot deal – but that applies only to that book. Many authors find an agent with their second, third or even fourth effort. So – keep the faith, keep writing and keep querying. Secondly, you aren’t at the end of the line in terms of traditional publishing quite yet.There are medium sized publishing houses, outside of that elite clique of international names, who will accept submissions direct from authors. Search the internet to identify them and then do exactly what you did with querying an agent, because it is an almost identical process.  First of all, you will have to establish if they are a bona fide medium sized publisher. That is simple enough. Their website will list their authors. You may not recognise some of their names, but that is probably because we are more familiar with the best-sellers list (the top 1% of authors) than we are with the mass of authors who make up the majority of the publishing market. You should also be able to find their books on the websites of the book retailers, both the ones that are on the High Street and the ones that operate online. If the publisher has only a handful of authors or titles, they aren’t medium sized, they are small (but perfectly formed, like us).  Many of the medium sized publishers concentrate on particular market sectors: romance, sci-fi, war and military etc. So, the next thing you need to establish is which publishers are going to be right for you. You are wasting everyone’s time if you submit to a publisher that doesn’t publish your genre and you are just leaving yourself open to the disappointment of receiving yet another rejection letter. There is no substitute for research. Like agents, publishers are inundated with submissions. For this reason, they often close for submissions for a few months at a time. Don’t upset the publisher by sending in your query when they say they are closed. They won’t read it. "Like agents, publishers are inundated with submissions." But also don’t be put off by the “closed” sign. Keep going back to the website to see if they have re-opened. If they have put out a date when they expect to re-open, make sure you visit that day and every day until the “open” sign goes up again. Persistence pays off. But, just like agents, medium sized publishers only take on a handful of new authors each year, so you are still fishing in a very small pond alongside tens of thousands of other anglers, so you may still be unsuccessful.  Now, back in Week 1 of this blog we made it clear that you should never part with money up front for publishing your book. We stand by that, but we also said there are times when you may need to pay for certain services. We are now going to look at one of those services. It actually falls under the heading of “self-publishing”, but it is of a particular type. For a fee, there are companies that will take your book and will print you a set number of copies for an agreed price. For some people this is a service worth paying for. It is essential, at this point, for us to be very clear about what these businesses offer. They will print your book for you, but they won’t sell it. Selling it is very much up to the author.

your book has, the trim size (the physical dimensions), the number of illustrations, the quality you want and other factors. The printers who offer this service usually have a menu of pricing options and provide a pretty good quality product – they wouldn’t stay in business if they didn’t. The problem usually comes from the minimum order quantity. Typically, this is around 500 copies, as it isn’t worth the printer setting up the presses for anything less.  I don’t know if you have ever taken delivery of 500 books in one go, but they are heavy (you’ll pay for that in the delivery charges) and they take up a lot of space. At 20 books to a box (about as much as one person can lift without risking injury), you are going to end up with 25 boxes minimum. Then you have to try to find outlets to sell the books, which means trekking around all the independent bookshops in the area (and probably further afield), trying to persuade them to stock a few copies on a “sale or return” basis. There are some specialist outlets you can also try, such as garden centres for gardening books, craft shops for crafting books etc but it still needs you to wander from each to the next with an armful of books and a hopeful smile.  Let’s have a look at the economics of this. If you have had 500 books printed at a cost £5,000, that means each book has to sell for a minimum of £10 just to break even. Then add about 50p to cover the delivery costs. The bookshop (or other outlet) wants to make a profit, so we’ll call that another £1 (they will probably want more, but we’re optimists) and you also want to see some income, say another £2. So, your book has to sell for a minimum of £13.50 per copy. But you are an unknown author. Are people going to be willing to pay that much? We will be discussing pricing in greater detail in a later blog. At the other end of the cost range, the book will have to sell at £6.50 plus for everyone to make something from it, but even that is a lot to pay for a book by an unknown author. But at that price you do stand a better chance of success and you have a bit more room to negotiate with stockists over their cut. The most likely outcome is that you are going to end up with a shed, garage, attic or even all three, full of unsold books. You’ll attend book fares and author events, of course, you’ll give away a few copies to friends and family for free and maybe donate a few copies to local libraries, but that still leaves a lot of books unsold. I know the most likely destination for them. "you do stand a better chance of success and you have a bit more room to negotiate with stockists over their cut."  There is a solution that allows you to sell to a wider audience and that is Amazon Marketplace. If you set yourself up with an account on that you can sell your book through their website, which thousands of people do for a wide range of products, not just books. Amazon will want a cut, of course and you’ll have to charge post and packaging, which adds to the cost of your book for the reader. But it does put your book in front of a much wider audience and you don’t have to trek around the bookshops and the garden centres to do it.  But no one is going to stumble on your book by accident, even on Amazon. You are going to have to do some marketing and we’ll be covering that in future blogs, because it’s such a huge subject in its own right. If you have a storage problem, there are three ways of dealing with it. The printer may agree to store your books for you, but they will charge you for the service. When you get an order, the printer will package and post your book for you. Not all printers offer this service. Amazon will agree to store the books for you in their warehouse and they will also distribute them for you. But, of course, Amazon will charge you for that as well. And if your book doesn’t sell, after a while Amazon will ask you to take your unsold copies back (or dispose of them in another way), to free-up space for more profitable products. Finally, there are “fulfilment” services. These are companies that hold stocks of products for a wide range of small online retailers (again, not just authors) and distribute the products on their behalf. But beware – not all of them have glitzy warehouses. Some operate out of their garden sheds or garages – just like you.  A modern POD facility. A modern POD facility. The 21st century innovation of “Print on demand” (POD) has changed the dynamics of this industry for the better. Your book is held as a computer file by the printer and when an order for it comes through, the book is printed, packaged and distributed. It normally reaches the customer within 3 – 5 working days. For readers that want paperback books rather than e-books this is usually acceptable and, because there is no physical book to store, you can keep your costs down. There are a number of reputable printers that offer POD services. Ingram Content Group are perhaps the best known in the UK market. This is NOT a recommendation, but a visit to their website will tell you more about how it works. Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) offers a POD service, which allows you to publish an ebook and a paperback side by side, linking the two products together. Most other self-publishing platforms don’t offer that facility.  So, you can’t find an agent, the medium sized publishers aren’t showing an interest in your masterpiece and you don’t want the hassle of having to store and sell hundreds of copies of printed books. What next? Well, this brings us to self-publishing and small publishing houses. Please don’t groan. There are thousands of authors just like you making a creditable income using this route. I know of at least one (I’m a fan of his work, but we don’t publish him, more’s the pity) who is actually in negotiations to have his books turned into a TV series. So, don’t knock this route until you have tried it. But that is the subject for next week’s blog. If you have enjoyed this blog and found it informative, make sure you don't miss an edition by signing up to our newsletter. Just click the button. Week 2 - How To Hunt A Unicorn  It may be considered that the search for an agent or a publisher makes hunting for unicorns look like a stroll in the park. Why is this? Well, it is because the number of authors outnumbers the number of agents and publishers by a lot. When I say “a lot” I’m not thinking 2 to 1, 5 to 1 or even 10 to 1. I’m thinking of tens of thousands to one. And that’s just in the UK. Covid-19 has further increased the number of new authors as lots of people have had more time on their hands than they really want and writing that first novel is a good way of filling time. One of our own authors, Arabella Aristo (that’s a pen name, by the way) is one such example, as she was unable to work during lockdown. Writing a book has never been more popular and, thanks to platforms like Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), Lulu, Kobo, Smashwords and others, publishing a book has never been easier. But those are self-publishing sites. What has that got to do with agents and publishers? Well, every author who self-publishes first tries to publish by the traditional route. So – back to that SWAG (statistically wild-ass guess) of tens of thousands to one.  When you submit your manuscript (MS) to an agent or a publisher, you are adding to a reading pile that is already several feet thick. The agents and the publishers can therefore afford to be very choosey about which MS they consider and which they toss in the rubbish bin. Our blog last week was about making sure your book is ready to go to the agent/publisher by getting independent feedback on it before you submit it. Now you can start to see why this is so critical. Each “query” letter/email is a one-shot deal. If your book isn’t up to standard, you won’t get a second chance with that agent. But let’s look on the positive side. Your book is a modern classic and the feedback you have received suggests that it is going to win the Booker Prize. Most major publishing houses don’t accept submissions direct anymore. It costs too much to pay people to read them. They only deal with agents and it is the agent who reads the MS. So, you want to find an agent. How do you start? If you’ve been in any of the usual social media hangouts frequented by authors, you will have read a lot out about “elevator pitches” and crafting the perfect “query” letter. For the uninitiated, an elevator pitch is a short speech to tell someone about your book. Imagine you are in an elevator and an agent gets in with you and you have until the elevator reaches his/her floor to tell them about your book – less than a minute probably. Let’s do a reality check here. How likely is that to happen? Not very. So why waste precious time developing the perfect elevator pitch?  Ah, but you can also use it to pitch your book on social media, like Twitter or in your query letter (for the sake of simplicity, assume “letter” also means email). Twitter members even do days called #pitmad, where people pitch their books. No. Trust me on this, agents and publishers aren’t trawling social media looking for the next Hilary Mantel or J K Rowling. They don’t need to. And if you use your elevator pitch in your query letter by saying “it’s like Game of Thrones crossed with James Bond” it isn’t going to tell the agent enough to excite their attention – mainly because they’ve probably seen it before. There is a place for the elevator pitch, but it comes much later in the process. It is useful in marketing your book, but we’ll come back to that in a few week’s time. The query letter is in the same vein and many authors agonise over composing the perfect query letter. Don’t get stressed about this. If your work is good enough, the letter will be read even if it is written with a blunt crayon. OK, present yourself professionally, but the query letter doesn’t have to be perfect, it just has to introduce you to the agent or publisher. All it really has to say is “here’s my book, submitted in accordance with your submission guidelines”. I’ll return to submission guidelines later as they are quite important. How do you find an agent?  In the UK I would recommend you buy the latest edition of “The Writers’ ℇ Artists’ Yearbook”. In it you will find a section on agents, including contact addresses, website details and email addresses. There is now also a spin-off website which has some other useful resources https://www.writersandartists.co.uk/ For children’s writers, there is a subsidiary book, “The Children’s Writers’ ℇ Artists’ Yearbook”. The one thing you can guarantee is that all the agents and agencies listed in the Yearbook are reputable and have a track record in publishing. The downside is that every author wants the agent to represent them If you are reading this book outside of the UK then there is probably an equivalent book and/or website where you live, but you’ll need to Google it. Some entries give information about the genres the agent represents but others don’t, so you may have to do some further research online to narrow down the field to those agents who are most likely to be interested in your book. Some entries also list authors that the agent already represents, so look for names that write in the same genre as you. If there aren’t any, they may not be the right agent for you. Most agents and agencies have their own websites these days, which makes life a lot easier. Visit the website and see what they have to say about authors and genres. Big agencies will list all their agents and from that you will be able to identify the one who represents authors most like you. Sending your book to the wrong agent is only going to have one outcome and you don’t want it. Time spent on this sort of research is never wasted. It is better to spend an hour finding the right name at an agency than it is to spend 3 hours e-mailing all the names in the hope of hitting the right one. This is particularly important when it comes to non-fiction. Most agents who represent non-fiction authors deal with a very narrow range of work. Sending your biography to an agent who only deals with autobiographies is a complete waste of time.  Now we come to the submission guidelines, which I will abbreviate as SGLs. These tell you how to submit your work to the agent or agency. Read them, take note of the content and DO WHAT THEY SAY. The SGLs have been created for a reason and that reason is not so you can ignore them. Firstly, they tell you how many words or chapters to submit. Why is that important? Because if your work doesn’t get the agent excited within that wordcount, they won’t be interested in reading any further. So, if you’re not sure your book can grab the agent’s attention within that wordcount – there’s no point in submitting it. Your beta readers should be able to help you there; ask them how quickly they were hooked on your book? And if you aren’t confident that your book will gain the agent’s attention – you can do something about that before you submit your MS. If you don’t do anything about it, why are you wasting people’s time? One thing you can do while you are actually writing the book is to assume that the last book an agent accepted was exactly like yours. So why would they now want your book if they have just signed one just like it? In that case, how are you going to make your book different from the one he/she just accepted? When you have answered that question, do it! Make no mistake – originality sells.  The other thing about complying with the SGLs are that they show your ability to work with a team. There are authors who have a reputation for being “difficult to work with” (translation: they’re a total pain in the you-know-what). Let me just tell you that you have to be a pretty brilliant author to get away with that. For most authors, the agent – and any publisher they connect you to – wants to know that working with you will be a dream experience – not a nightmare on Elm Street. Adhering to the SGLs is your way of showing what a sweet natured, team player you are. And if you aren’t – fake it. Most SGLs ask for a synopsis of the rest of the book. This is so the agent can see how the story develops and comes to its conclusion. Now, two things about the synopsis:

Here’s a blog from an experienced publisher about how to write a good synopsis. It is on the synopsis that you should be concentrating your time and effort – not elevator pitches or perfect query letters. There is a reason why the synopsis is usually limited in length and it is so the agent can see if you can express your thoughts concisely. If your synopsis rambles on for three or four pages, then your MS is also likely to ramble on (just like this blog). It is quite probable that the agent will read the synopsis before the MS, so you can see how you will start to influence their thinking if you get it right – or wrong. Agents and publishers want to form long term relationships with authors. Long term relationships spread over several books pay the bills year after year after year. This is where your query letter is important, unless they ask for a biography.  Tell them what plans you have for future books. Harper Lee may have written a 20th century classic, but she didn’t earn her agent or publisher much money after the initial sales surge. Nowadays she would be lucky to get a book deal if she said, “I’ve only got plans for one book”. Publishers particularly like series. If a series catches on, they become real money spinners; just ask J K Rowling and George R R Martin If you are asked for a biography, then keep it short and simple. Bullet points work best: name, age, family circumstances (married, single, children etc), education, current employment, hobbies and interests and, finally, plans for future books. Once you have selected your agents (note the plural) submit to several at the same time – I’d say at least 3 or 4. First of all, if you wait for each one in turn to get back to you before sending out the next query, you are going to be querying forever, Secondly, ideally you want to get into a bidding war, with agents vying over you and competing to give you the best deal so you will sign with them.  To start that bidding war you can’t get an acceptance and then query a second time, because that shows lack of integrity. You’ll lose that acceptance and you’ll probably put off the rest of the agent community. They do talk to each other and compare notes, you know. The next step for the agent after reading your initial query submission is to ask you for the full MS. It is very important for the MS to be ready to go. The agent isn’t going to wait for you to finish writing the book. They have a stack of other queries four feet high to be getting on with and by the time you have finished writing your MS, they’ve moved on and you’ve missed your big chance.  Now, inevitably, we get to what to do about rejections – because you will get rejections (or, worse, you won’t get a response at all). Legend has it that J K Rowling had 60 rejections before getting Harry Potter accepted. Whether that number is accurate I have no idea, but Rowling herself admits to being rejected by several agents before being signed by Christopher Little then, when she did find him, the book was rejected by 12 publishers before being taken up by Bloomsbury. And, of course, we all know that Decca Records rejected The Beatles, much to EMI’s profit. The main thing to bear in mind is that a rejection doesn’t mean your book is bad. Just remember what I said about tens of thousands of authors and only a handful of agents. Each agent may only take on one or two new clients a year and they will be the ones that don’t just stand out from the crowd, they are the ones that tower over the crowd. Agents rarely say why they are rejecting your book and, for all you know, your book may have been just a hair’s breadth away from being accepted. Send out your query letter again to the next batch of agents on your list. You never know which one is going to be the one who takes your book. But, in the end, you may get to the end of the list of agents without ever catching your unicorn. But that doesn’t mean you’ve reached the end of the road. Next week we’ll be taking a look at medium sized publishers and paid for publishing. We hope you have enjoyed this blog and found it informative. If you want to make sure you don't miss any future editions, please sign up to receive our newsletter. Just hit the button. |

AuthorThis blog is compiled and curated by the Selfishgenie publishing team. Archives

June 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed