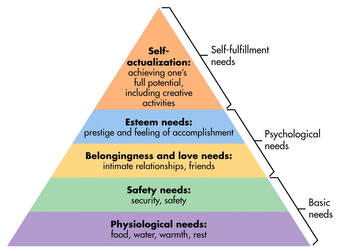

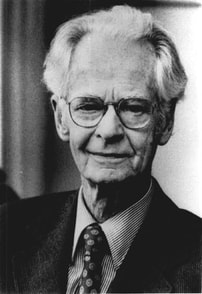

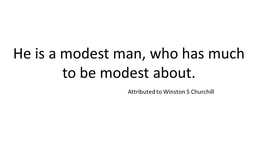

Understanding a protagonist’s motivation is one of the critical factors in creating interesting characters for stories. In fact, we will go further than that and say that authors should be doing the same for antagonists as well. But in order to do that we also need to understand how and why motivation works in general otherwise we can’t attribute the right motivators for the correct reasons. For example, if our story involves a love triangle, what might motivate one of the characters to abandon their love in order to make the object of their love happy? In a selfish world like ours that makes no sense. But it is a well-used trope in romance. Which is what this week’s blog is about. It’s a whistle stop tour of motivational theory and what it can do for you as an author.  The first thing to understand is that there is a significant difference between motivation and incentive. The big difference between the two is that an incentive can never be enough for a person to place themselves in jeopardy. After all, there’s no point in being paid £1 million (an incentive) if you are going to end up dead and can’t spend it. But a person may take a dangerous, high paying job if it is the only way to provide security for the ones they love. Love is a motivation, money is an incentive. To put it another way, motivation drives us, but incentives can only attract us. In fiction we are always looking for what drives the character. The lure of wealth may be an incentive for a criminal, but it carries the risk of imprisonment. So, what motivates criminals to take that risk? Understanding that motivation makes the criminal far more interesting than just the lure of wealth, which is a shallow incentive.  Psychologist Abraham Maslow Psychologist Abraham Maslow Theories of motivation are generally grouped under one of two headings: content and process. Content theories focus on what things provide motivation and process theories focus on how motivation occurs. To add depth to a character it isn’t enough to know what motivates them (content) it is also important to know why (process). The two together provide layers of complexity and that makes characters more interesting. Abraham Maslow is the grandaddy of content theory. He theorised that in order to function at a higher level, you first require certain needs to be satisfied. In other words, you can’t create great art if you are starving to death. So, you have to have your hunger satisfied before you can achieve your goal to become an artist. This became known as a “hierarchy of needs”. You may, at this point, be tempted to mention the name of Vincent Van Gogh, who only sold one of his paintings during his lifetime. But he wasn’t actually poor. He had a very well paid job selling art in his brother’s Paris gallery before he left to pursue his own artistic career. He wasn’t penniless at the start of his career – though he may have been by the end.  Maslow's Hierarchy Of Needs Maslow's Hierarchy Of Needs In practice this means that we are first motivated by a need to survive, but if that is secure we can then move on to be motivated by something at a higher level. In fiction this means that if a character is trapped inside a burning building, they aren’t going to be interested in catching the person that struck the match. Only after they have escaped the inferno will they think about that. A vagrant living on the street wouldn’t be motivated enough to help a damsel in distress, because their priority would be their own survival. But they can be incentivised to help the damsel because the incentive (usually money) secures their basic needs. However, if it looks like they may die in the attempt, the incentive would no longer be enough. They would need some other motive, such as love for the damsel. While good Samaritans may exist, they don’t place themselves in danger. They need motivation for that to happen. As can be seen from that example, content-based motivation is a tricky business and if you don’t understand those sorts of basics, your readers won’t believe in your characters.  But what content theory also makes clear is that what motivates us isn’t constant. Our motivation can change in response to circumstances. For example, we may be highly motivated to succeed in our careers, working long hours and totally immersing ourselves in our jobs. Then one day we meet the girl (or boy) of our dreams and suddenly our career isn’t the most important thing in our lives anymore. Winning the heart of the object of our desire is now what is uppermost in our minds, to the extent that we may throw away our career in order to be with that person. That, of course, runs contrary to Maslow’s theory, because if we lose our job we also lose our security. So, it appears that some motivators are more powerful than others, at least for some of the time. Achievement and competition are theories of content motivation studied by David Mclelland. Today this is often portrayed in fiction as a negative thing; highly motivated achievers or competitors are often depicted as criminals or cheats, driven by their desire to win at all costs. Which is odd, because the sports stars we admire the most are highly motivated by competition and achievement. Not only do they compete in their sporting arena, they also compete off the field by gaining more public acclaim. In modern fiction, the highly motivated competitor that you admire so much would be portrayed as a cheat, because that is the trope that fiction writers use. Competitiveness = negative character traits.  Psychologist B F Skinner Psychologist B F Skinner Is competition and high achievement a bad thing? That is for you to decide, but I know of one author who uses competition as a motivator for the success of his heroic characters. When it comes to process theories, there is one that is usable in fiction. It is “reinforcement” theory, developed by B F Skinner. This is based on positive outcomes of certain types of behaviour. In fact, this can be traced back even further, to Pavlov and his dogs, but Skinner is better known for his study of humans. If you can imagine a misbehaving child being given a biscuit (cookie) in exchange for better behaviour, it will soon learn that if it misbehaves biscuits (or cookies) will be forthcoming, so that the reward becomes the motivator for bad behaviour. Extending that theory into adulthood, if a character believes that rewards come from bad behaviour they will continue to behave badly – which is great motivation for criminal characters. The opposite applies as well, of course. If good behaviour results in good outcomes, then a character is motivated towards good behaviour. It may also surprise them when their good behaviour results in a bad outcome, eg their loyalty being betrayed. That could be enough for a previously good person to start behaving badly.  Because when we add emotions to motivation, we start to get a powerful mix. I have already mentioned the power of love to derail a career, but there are plenty of other emotions that can drive motivation: fear, jealousy, hatred, greed, disappointment, pleasure, etc. The most challenging question it is ever possible for an author to ask is what makes one man brave and another a coward. This is especially so in stories that involve death but can also be played out in terms of moral behaviour. Nature has given us three responses to danger: fight, flight or freeze. What makes one person choose to fight, another choose to flee and another to do neither (freeze)? Fear is a natural response to danger, so all three responses should be regarded as equal, because nature gave us the choice even if we don’t make it consciously.  But our high regard for bravery and our contempt for cowardice shows that we don’t regard all three responses as being equal. Very often the individuals who take the actions can’t answer our question. Ask most decorated war heroes why they did what they did, and they are unable to answer, or they fall back on cliches like “duty”. But duty only takes us so far. A soldier standing firm in the line of battle is doing his duty. A soldier that charges an enemy position in order to save a comrade is going far beyond that. It happens in real life, but quite rarely which is why medals such as the Victoria Cross and the Congressional Medal of Honour exist to recognise such actions. But in fiction it is the norm for the protagonist to exhibit that level of bravery.  However, the brave person isn’t unafraid. The brave person is one that overcomes their fear. But what motivation is so powerful that it able to make people face down their fear and do incredibly dangerous things rather than running away? So, what can we give them, in emotional terms, so that they do that? And, more importantly, how can we create a backstory that shows how they developed that quality, based on what we know about motivation? This is where Skinner’s theory becomes important. If, during their developmental years, the character is rewarded for having beliefs and values that we admire, but isn’t rewarded for having beliefs that we detest, the qualities for which they were rewarded will become the motivators. They will also become the barriers when those qualities are undermined. The flawed protagonist is one whose beliefs and values are called into doubt by events, which cause them to question their beliefs and results in an internal conflicts. There is far more to motivation than I have had time to cover in this blog. I recommend further research. How much of that you include in a story is up to you, but layered characters with strong motivations are always going to be of more interest to readers than shallow characters who only respond to incentives. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.

0 Comments

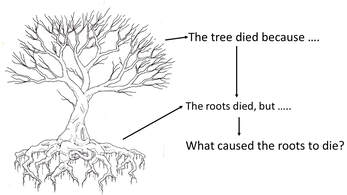

Creativity is a basic skill for being a writer. Your imagination is what creates stories. Every best-selling book started with an idea popping into the head of the author. The author then nurtures and feeds the idea until it starts to gain form and flesh, in the shape of sentences, paragraphs and chapters. No two authors are alike, so the techniques that each author uses to create their story will be different. We are familiar with the terms “plotters” and “pantsers”, but those are only two types that form the extremes of a very broad spectrum. Sometimes, regardless of whether they are plotters, pansters or somewhere in between, authors run out of ideas for taking their story forward. They may call it writer’s block, or they may use another term, but for some reason they just can’t come up with what is going to happen next in their story. But all is not lost. You don’t have to sit there looking at a blank screen (or a blank sheet of paper if you are more “old school”). There are tools and techniques that can be used to stimulate creativity.  I would love it if creative problem solving techniques were taught in schools, as they have a direct application in any workplace. But they aren’t. What you can do, however, is take a few of these techniques and maybe make them work for you as an author. The best creativity comes from working with others. By combining brains and “bouncing” ideas off other people, the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts. However authors are, by nature, solitary workers. That solitude presents a challenge, but one that is not insurmountable. Last week we heard from Gene Ramsey about how to unlock some of your creativity by taking control of your writing environment. This week we would like to take things one step further and suggest some practical techniques you can use to create new ideas. So, enough preamble, let’s get into the details.  “What if” scenarios. This does what it says on the tin. If you are stuck thinking about what your character should do next, asking “What if they did this …” allows you to test ideas out. The basis of “what if” scenarios is rule breaking. You are going to make your character do something that may be physically impossible, morally or ethically wrong, might get them killed, might get someone else killed and a whole lot of other things that might, normally, prevent you from considering taking the character in that direction. But that is OK. Having created the scenario, you can then challenge the idea not in terms of not doing it, but in terms of still doing it, but in a way that will make it work. You are building up, not knocking down. In creativity it is always about building up, not the other thing. My character can’t do “that” because they would burn to death. OK, how about I find a way of them doing it without burning to death? Can I give them a fireproof suit? Can they find a way to extinguish the flames? Can I use magic to protect them? You get the idea. So, the character will still take the path you imagined with your “what if” scenario, because you have found a way of making it possible. But the key barrier to the what if scenario is assumptions. We make them all the time, sometimes without thinking about them. You have to learn to not only identify assumptions, you have to learn to challenge them. You will be surprised how often assumptions are actually wrong. Scientists and engineers find that out every day. And if you doubt me, remember that only 120 years ago it was assumed that it was impossible for humans to fly.  Quantity, not quality. This is the basis of one of the best-known creativity tools, brainstorming. Basically, you generate idea after idea, without worrying whether they are good, bad or indifferent. Normally this is seen as a team activity, but you can do it yourself. All you need is a pad of sticky notes and a surface on which to stick them. Write your ideas on the notes and slap them on the white board, wall or whatever. Lots of them. They don’t even have to have anything obvious to do with your book. The whole idea is to get your brain spewing out ideas in a constant stream, because amongst the thousands of bad ideas that may come out, there will be a few golden nuggets. When you have finally run out of ideas (you should try to keep going for at least an hour) you can start to group the ideas together in terms of common themes. Those themes can then be examined more closely to see what they have to offer. Maybe you didn’t come up with “the” idea, but perhaps by combining ideas a, b and c together, you may have something you can work with. A similar technique involves writing the ideas on a pad, page after page of them. Then tear up the first two pages, because they will be too “normal”. The real gold will appear on the later pages, when you started to get desperate for ideas and your brain had to keep going, drawing more and more from your subconscious mind.  Flip the Point of View (POV) Authors sometimes get so hung up on what their protagonist is doing (or not doing) that they sometimes forget that there is more than one character in the book. By switching your point of view to see the problem through a different pair of eyes, you may see the flaws in your character’s (your) thinking (the paradigm they (you) are working within) which will allow you to break them out of the status quo. For example, if your protagonist is a cop and the paradigm for a cop (an honest one, at least) is that they can’t break the law, then the way forward for the protagonist might be blocked But if you view the problem from the POV of a lawyer, you might find that there is a loophole in the law that would allow your protagonist a route out of their problem. But you won’t see that loophole if you are still thinking like a cop, so you have to think like a lawyer. You can also look at the story from the antagonist’s point of view. What is the thing the antagonist would least like the protagonist to do? That is what you should have your protagonist do. You can look at the problem through the eyes of several other characters, to see how they would deal with it. Shifting the paradigm in this way is a fundamental in organisational problem solving.  Use Analogies I’ll start this section by asking you a question. What has Formula One (F1) motor racing got to do with the airline industry? The answer is very simple when you think of the question as an analogy. A feature of F1 racing is the speed at which pit crews are able to get a car in and out of the pits for tyre changes etc. It depends on two things: (1) having everything where it is needed, when it is needed and (2) having well practised drills, so everyone does their job instantly without having to think about it. Back in the late 1970s, when cheap air travel started to become a thing, airlines were looking for ways in which they could get more flying hours out of their aircraft, because an aircraft sat on the ground isn’t earning any money. They looked at the problem from the perspective of F1 racing, and realised they could adopt some of the same techniques to get their aircraft turned around at airports far more quickly, saving several hours a day in some cases. Now all the budget airlines use the same techniques to get their aircraft back in the air as quickly as possible. Businesses use analogies of this sort a lot to come up with new ideas to streamline their performance. And you can use the same technique to come up with new ideas for moving your plot forward. So, in terms of solving your character’s problems, what sorts of analogies might you use to stimulate your thoughts?  Zoom Out From The Problem How often have we heard the expression “can’t see the wood for the trees”? We are so stuck down in the weeds of the detail of a problem that we can’t see the bigger picture. So, the solution is to “zoom out”, so we are no longer able to see the individual trees, but we can see the whole forest. And if we can see the forest, we can also trace all the possible paths through it. I’ll give you a hypothetical situation. Your character is stuck at the bottom of a well. There is no way for them to climb out and the rope that holds the bucket is rotted through, so they can’t climb it. They are shouting for help, but there is no one to hear them at the top of the well. Because you are so close to the problem, all you can see right now is a deep dark hole with no way out of it. But if you were to zoom out, you might see a church with a belfry. And the rope that attaches to one of the bells in the belfry is broken. You might also see that on the other side of the forest lives the chief bell ringer. They know about the bell rope and they have a replacement. So, they cross the forest and their path takes them close to the well, where they hear the protagonist calling for help. So, you now have a rope and someone to drop it down the well to rescue your character. But you only got to that point because you zoomed out from the well to take in the wider picture. OK, that is a literal interpretation of the theory. But it does work. If you can detach from the detail of the situation in which you have placed your character and look at the bigger picture of the story and imagine what else COULD be happening, you may well find the solution to your problem. Incidentally, you can combine "zooming out" with the "what If" scenario to make it even more effective.  Mind Mapping Again, this is a long-standing technique that works for many people. Basically, you place the problem in the centre of the page and then map all the different aspects of that problem, to see where the barriers are lying. For example, one branch of the map may relate to your character’s family constraints. Another may relate to their skills and knowledge. A third might relate to the resources available to them. Another may be their emotional entanglements. Another is the mental baggage that they are carrying around. As you explore each branch you should be able to make smaller branches that deal with other aspects of the same problem and you may be able to link some of the issues in one branch with some of the ones in other branches, because they are connected in some way. Once you have a detailed mind map, you should be able to identify possible solutions to what is causing your creative blockage. Mind mapping makes use of the key questions we always ask: who, what, where, when, how and why. Here’s a link that describes mind mapping in more detail. This technique isn’t just useful for overcoming writer’s block. It’s also a great way to get a new story idea worked out in more detail. Conclusion I have only been able to scratch the surface of the wide-ranging subject that is creative problem solving. Enough, I hope, to get you started. But if you go online and search “creative problem-solving tools” you will find a wealth of information. Some resources you may have to pay for, but others are available for free. Images credit: pexels.com If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so. This week we are delighted to post another guest blog by Gene Ramsey. This time he takes a look at how to refresh your creative juices when they are flagging a little. All images courtesy of Pexels.  As a writer, the ability to tap into your creative wellspring is indispensable, yet there are times when the muse seems elusive, and your imagination feels as barren as a desert. In these moments, the need to recharge and revitalize your creative spirit becomes paramount. This article explores practical strategies tailored to help writers and authors break free from creative stagnation, ensuring a vibrant and fruitful engagement with your craft.  Disconnect to reconnect In this digital era, it's essential to consciously detach from the ever-present screens of your smartphone, computer, and tablet. Allow your mind the freedom to meander through thoughts without the interruption of incessant notifications and the relentless influx of information. In the tranquillity of this newfound mental space, as you gaze out the window or simply let your thoughts roam, your next ground-breaking idea might subtly make its presence known.  Establish a Sanctuary for Creativity As a writer, your craft demands undivided attention. Designate a sanctuary where you can isolate yourself from the world's distractions. This dedicated space should invite tranquillity and allow for uninterrupted flow of thoughts. Whether it’s a quiet corner of your home or a secluded part of a local park, make this space your own. Regularly spending time in this creative haven can help you establish a routine that, over time, will signal to your brain that it’s time to engage creatively.  Play Your Way to Innovation Remember, creativity is not all about stern expressions and furrowed brows; it's also about play and exploration. Reconnect with activities that light up your spirit and make you feel alive. Whether it's sketching, playing board games, or crafting, these playful acts can subconsciously stir up ideas and inspire innovative thinking. Allow yourself regular playtime; it’s not frivolous but a fundamental part of nurturing a creative mind.  Harness the Power of Video Creation Venture into the dynamic world of digital storytelling by creating your own videos, opening up a vibrant avenue to communicate your narratives. With a free video creator online, you can experiment and enhance your projects without any financial strain, providing a cost-effective way to bring your visions to life. This tool not only allows you to add audio and animate elements but also enables you to manipulate video speed, enriching your storytelling with a professional flair that captivates your audience.  Revisit Childhood Joys Reengage with the activities you loved as a child to tap into pure, unadulterated creativity. Childhood is a treasure trove of imagination and wonder—qualities that are often muted in adulthood. By revisiting these past joys, whether it’s reading comic books, doodling, or building model airplanes, you can reignite the imaginative spark that once came so naturally and infuse your writing with renewed passion and enthusiasm.  Art as a Pathway to Creativity Use art as a therapeutic way to explore tools to unlock new creative realms. Artistic expression transcends words, allowing emotions and ideas that might be difficult to articulate through writing alone. Engage in painting, sculpting, or drawing to visually express what lies beneath your conscious mind. This not only provides a therapeutic release but also deepens the well of creativity from which you can draw as a writer.  Write Freely and Fluidly Dive into the realm of free writing; unleash your inner stream of consciousness directly onto paper without the constraints of perfect syntax or punctuation. As you write without stopping, you'll navigate past the barriers of writer's block and discover hidden ideas that lurk beneath your structured thinking. This technique not only refreshes your mind but also enriches your narrative skills by revealing unexpected insights and themes.  Dream a Little Dream Your dreams are a direct line to your subconscious, where much of your creativity is housed. Make a habit of keeping a dream journal by your bedside. Upon waking, jot down as much as you can recall about your dreams. Over time, you may find that these abstract and often bizarre dreamscapes serve as excellent fodder for creative projects, offering unique imagery and plot twists that can set your work apart. Recharging your creative batteries as a writer involves a blend of structured solitude and unstructured play. By adopting these practices, you not only enhance your creativity but also enrich your life, making each written word a reflection of a fully lived experience. Rediscover your creative spirit and watch as your writing transforms from mere words to vivid worlds that captivate and inspire. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  We have to talk about blurbs again, don’t we? In writers’ groups on social media, I am still seeing such awful blurbs being posted, inviting feedback, and I have to wonder why authors don’t realise how badly they are showcasing their books. There are so many blogs and books about blurb writing, they all say similar things (including this one) and they are all quite clearly not being read by authors. If they were the blurbs wouldn’t be nearly so bad. I’ll be recommending one of these books later. I suspect that it is because authors view writing a blurb from the author’s end of the telescope. They have lavished weeks, months or even years of effort on their story and they want to tell the reader as much as possible about it in their blurb. But instead of making the book sound exciting, they try to tell the story in 300 – 500 words and that just does not work. When you view the same thing from the readers’ end of the telescope, the blurb looks very different. In the blurb all the reader wants to know is “Will I like this book?”.  Creating a blurb is not a writing exercise, it is an exercise in psychology. Everything about a blurb has to say “this is the best book you will read this year” while actually saying something completely different. Every word has to have meaning for the reader in a way that they don’t even recognise. Which is why trad published authors don’t do their own blurb writing. Trad publishers hire specialists to write blurbs. People who know how the psychology of blurbs works. So, as well as writing, editing, proofreading, cover design and marketing, self-published authors have to add a new skill set to their arsenal, and it’s called copywriting. It is a major skill used in advertising of all types and a blurb is just another form of advertising. The buying of a book is a lengthy process. It may only take a few minutes, but in psychological terms it is a lifetime of decision making.  We call these decisions the “sales funnel”. It’s the basic process that takes place between the reader first seeing your book ("awareness" in the graphic) and the point at which they click (or tap) on the “buy now” button. The thing is that in terms of the “sales funnel” the blurb is only about halfway along the path. (The "interest" section of the graphic). But if the reader isn’t attracted by the blurb, they won’t take the next step along the path (desire), so the sale is lost. Think of a blurb like a bridge across a river. On one side you have the book’s cover, title, subtitle and price, and on the other side you have the free sample (which stimulates desire), next to which is the “Buy Now” button. The Bridge of Blurbs allows the reader to cross from one side of the river to the other. I’ll return to the latter stages of the sales funnel at the end of this blog, just to remind you of what they are. But first I want to talk about the barrier of the “read more” button.  When you look at a blurb on Amazon you are only shown a few lines of text. The more “white space” the author has included, the less text there is to read. Then comes the “read more” button which will reveal the rest of the blurb. Now, ask yourself this question. If you haven’t got the reader’s attention after those few lines of text, will they click on that “read more” button? I think you already know the answer, but just to make it clear – No, they won’t. They will go and look at a different book. Getting the reader to click on the “read more” button is the first challenge to be met by the blurb. It is a barrier to sales that can be as big as the Great Wall of China.  Let’s start with the “tag line” because that is usually the first bit of the blurb the reader sees. So, what makes a good tag line? It is one that forces the reader to ask questions. If they start to ask questions, they will want to know the answers and that means reading the rest of the blurb. I came across this example of a great tagline. It’s from self-published bestselling author Mark Dawson. “MI5 created him. Now they want to destroy him.”* The first thing to notice is that there is clear signal as to the genre of the book. “MI5” can only mean spies and secret agents. If the reader likes those sorts of books, they are likely to read on. But those two sentences also invite the reader to ask questions.  With your “reader” hat on, start asking some questions about those 2 sentences. I got “Who is the ‘him’ that is referred to? Why did MI5 create him? What did they create? An assassin? A Spy? Why do they want to destroy him? What did he do wrong? Will they succeed? And, the 2 sentences together add up to one thing – betrayal. So, the reader is almost bound to feel some sympathy for the character and sympathy is a powerful emotion to invoke. Importantly, they will start to read the rest of the blurb in an effort to find some of the answers to their questions.  That isn’t the only type of tag line you can use. Some authors use a quote from their reviews, and they can work well. Research has shown that click rates for review quotes are quite high. Quotes work because readers identify with other readers. It’s a bit like being part of a club. But reading the tag line is like seeing an attractive person across a crowded room. They look nice, but are they interesting? So, you go across the room to talk to them to find out. After initial introductions, they start to talk.  “I was born in London, but my family moved to Nottingham when I was 5. I went to primary school at … then secondary school at … before starting at university where I studied …. After that I went to work at … My brother went to … and he lived with my Auntie Vi. She’s a …” Are you bored yet? Are you looking over their shoulder to see if there is anyone more interesting you can go and talk to? So, imagine your reader’s boredom when you start to tell them all about your character’s backstory, or the world you built for them, or their extensive family tree and all the other things authors stuff into their blurbs. Yet the author still expects the reader to click on the “read more” button despite the fact that they have already sent the reader to sleep.  The second para has to tell the reader what the story is about. Not the whole thing of course. You introduce the protagonist, drop in tropes that indicate the genre and the type of story within the genre. But above all you introduce the conflict because the conflict starts to raise emotions in the reader. They start to like the protagonist, they start to sympathise with them. In short, they start to engage with them. To do that you have to use words that trigger emotional responses. “Vulnerable” is one such trigger word, often used in romance. “Courageous” is one seen in action adventure, sci-fi, fantasy and more. Below is a list of words that trigger an emotional response. There are many more, of course, but these are seen frequently in blurbs. The reason they are seen so frequently is because they work. You only need to use a couple to get the reader responding at an emotional level. Sympathy is a particularly powerful emotion. If the reader sympathises with the character’s plight, they are going to want to know what happens to the character. Which means that the character can’t be a victim. People don’t actually sympathise with victims that much because victimhood is passive. What they do sympathise with is a victim that is fighting back, because that is active.  If you can start to raise those emotions the reader will click on that “read more” button and you are a long way through the funnel to getting them to buy the book (but still not the whole way). So, the author has to hit the reader between they eyes with the sorts of words that are going to excite their imagination. These are called hooks, because they hook the reader into reading more. A hook at the end of a paragraph encourages the reader to move on to the next paragraph, so you can’t have too many of them. Hooks are often multi-layered. The top layer invites questions, the next layer invites an emotional response, the third layer will raise the level of the drama. But the most important part of the hook is the bit that will appear above the “read more” button. If it is hidden from view it might as well not be there because it may not be seen at all.  Most blogs you will read on blurb writing agree that the “sweet spot” for the length of a blurb is between 250 and 350 words, around 100 (40% or less) of which will be above the “read more” button.. Anything more than that and you will lose the reader, and they’ll move onto the next book in the search results. YOU CANNOT ALLOW THAT TO HAPPEN Many authors put a call to action (CTA) at the end of the blurb. This is not a good idea because the reader is not yet ready to buy. They will see the CTA as being “pushy”.  If that was the right place to put the CTA, Amazon would put one in - and they don’t. Amazon puts the CTA at the end of the free sample, because that is when the final decision to buy will be made (I’ll return to that in a moment). But that doesn’t mean there is no CTA in the blurb at all. Any good blurb will have a CTA, it’s just that it is disguised. The form of disguise is the “cliffhanger”. This can be a statement eg “Her survival is at stake …” or it can be a question eg “Will she survive …” Note the use of an ellipsis rather than a question mark. It leaves things open ended and that is good for keeping the reader engaged.  If the blurb has done its job, the reader will now go to one of two places on the sales page as they take the next step along the sales funnel. They may scroll down to the reviews because, as I said, readers like to know what other readers thought of the book. Notice I didn’t mention the product information, which they will have to scroll past to get to the reviews. That’s where the sales rankings are displayed. Interestingly , readers don’t seem to bother with them too much. Sales ranks seem to bother authors far more. I’m sure readers do look at the product descriptions, but they don’t seem to influence sales. If the book is so new it hasn’t had any reviews, it doesn’t mean the sale has been lost. Readers aren’t stupid. They know that a brand new book won’t have reviews. So, they will take the final step along the sales funnel to the “free sample” (previously called the “look inside” segment).  Your book has excited interest and kept the reader on the page, but the free sample stimulates the desire for the book. If the free sample doesn’t keep the reader interested until they reach the “buy now” button, there is no desire and the sale won’t be made. This isn’t universal, of course. A percentage of readers will buy without even reading the blurb, because the book has been recommended to them by someone whose opinion they trust, or they are familiar with the author and like their books. It may even be the long awaited next book in a series. A percentage of readers will buy on the strength of the blurb alone. A percentage will buy because they trust the reviews. But by far the largest percentage of sales come from the free sample. So, why so many words dedicated to how to write a blurb?  Because the blurb is part of the sales funnel and if the reader isn’t captured by it, they won’t get to the reviews or the free sample. They can’t get to the other side of the river without crossing the Bridge of Blurbs. At the top of the blog I mentioned a book on blurb writing that I would recommend. It gets deep into the psychology of blurb writing but it isn’t heavy. It is Robert J Ryan’s book “Book Blurbs Unleased.” If you only ever read one book on blurb writing, make sure it is this one. It’s free to download on Kindle Unlimited. * The use of bold text for the tag line was deliberate. Tag lines should always stand out from the rest of the words. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.