|

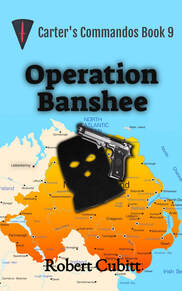

Disclaimer: We are not connected with Bryan Cohen in any way and have no financial interest in his book. This review has not been paid for by Bryan Cohen or anyone else.  This is a review of one of two books by Bryan Cohen that we think should be read in the right order. This first one, “Fiction Blurbs: The Best Page Forward Way” is about improving your blurb writing technique so that readers feel more compelled to buy your book. The second book, “Self-Publishing With Amazon Ads” teaches you about increasing the profitability of your advertising campaigns. What links the two? One of the “tweaks” that the second book suggests to increase sales is to improve your book’s blurb. So, if that is a tip for increasing sales it seems sensible to us to try to improve our blurbs before we started spending money on advertising, so that we don’t spend money on advertising only to find out that our blurbs might need improving.  Still not quite right! Still not quite right! It is putting the metaphorical horse in front of the cart rather than behind it. But don’t worry, we’ll be reviewing “Self-Publishing With Amazon Ads” next week, so that you can get the whole picture. Having said this book is by Bryan Cohen I must now correct myself and tell you that it is actually written by Phoebe J Ravencraft, an associate of Bryan Cohen, who works for his company, Best Page Forward. But they get joint author credits. First of all, what about the authors’ credentials for writing a book such as this? Best Page Forward has written over 5,000 book blurbs for self-published authors. Phoebe herself has written or overseen the writing of around 3,000 of those. She comes from an advertising copywriting background. They have gathered plaudits from satisfied customers and the blurbs they have created have stood the test of time to sell books. I think we can safely say that they know what they are talking about.  In one of our marketing blogs, repeated last autumn, we advised selling the sizzle, not the sausage. In other words, we recommended not trying to describe your book to the reader but trying to excite their imagination about how dramatic/entertaining/insightful/hilarious (insert other adjectives of your choice) your book is going to be. That is exactly what this book strives to do. That was good enough to convince me to buy the book. If it does that for us, the money spent on it will be repaid just by selling two extra copies of one of our books. As both an author and a publisher I have written dozens of book blurbs, so I thought I knew what I was doing. We had done plenty of research to try to find out what made a good blurb and we followed the lessons we had learnt, but there was still a nagging doubt in our minds that we might not be getting it right. Our sales suggested that there was something amiss. We were getting lots of clicks on our adverts, but they weren’t converting into as many sales as they should.  So, when I started to read this book, pennies started to drop to tell me that doing what other people were doing was the problem. What we needed to do was to be different, to make our blurbs stand out from the crowd. Readers are too easily distracted by metaphorical shiny things, so the solution to that is for our book blurbs to be the shiny thing that distracts them from other books. Chapter by chapter, Phoebe (if she’ll permit me the liberty of addressing her by her first name) lays out the elements that go into writing the “killer” book blurb that we wanted, and then how to structure the different elements to get the most out of them. It wasn’t that the blurbs we wrote were actually bad. After all, we're conforming to what we understood to be “best practice”. It was more that they could have been so much better. For the most part, they were selling the sausage, not the sizzle. They described the book, but they didn’t describe the emotional ride that was contained within the book. Emotions, it turns out, are the sizzle that sells the sausage.  I sort of knew that already, because I have always believed that books should be character led, not plot led. Readers engage with the characters at an emotional level and come to care about them and that is what keeps them turning the page, not the plot itself. And that emotional engagement, it turns out, is what has to be at the heart of the book’s blurb. There is a lot more to it than that of course. Conflict, jeopardy, structure and vocabulary all play a massive part, but without the emotion the book still won’t sell. I’m not going to ruin the book’s sales by telling you what tools and techniques are taught within its covers. You’re going to have to pay to find out, just as we did. Suffice to say that every page provides something new to learn. Even if your blurbs are already good I feel quite confident saying that you will learn something new from this book. Readers will note that I have given the book only 4 stars where, from what I have said, you might expect that it should be worth five stars. That isn’t because of the lessons that the book teaches. It is only because of the style in which those lessons are taught. "As an author and as a publisher I have limited time available" The author uses well known books and films to illustrate the lessons and there is nothing wrong with that. Many of those books and films are her personal favourites. Again, there’s nothing wrong with that. However, at times I found that the point being made was laboured and that the author was getting rather carried away with her own passions. While such enthusiasm is to be admired, it can be a little too much when the reader has already grasped the key message and only wants to move on to the next lesson. As an author and as a publisher I have limited time available, and this book took a little more time to read than was essential. Perhaps it was designed to pad the word count, so the reader thinks they’re getting value for money, but the real value isn’t in the number of words, it’s in the messages. But that is a minor criticism and I feel secure in saying that anyone buying this book will have their money repaid quite swiftly if they learn the lessons and apply them to their blurb writing.  So, what are my main takeaways from this book? The first one I sort of already knew but being reminded of it didn’t hurt. The purpose of the blurb is not to describe the book; it is to sell the book, which is an entirely different technique. According to Phoebe, you don’t even have to read the book to be able to write its blurb. Secondly, creating a good blurb isn’t easy and it requires practice and hard work. I soon discovered that when I tried to re-write the blurbs for the books we publish. What I thought would be about ten minutes work per book turned out to take considerably longer and they still aren’t perfect (though they are better). Finally, a good blurb taps into your emotions and raises the “risk” level for the protagonist so high that the reader has no choice but to buy the book to find out what happens. Get that right and the book will sell. But I’m sure you want to know if re-writing the blurbs for our books made any difference to our sales.  First of all, judge for yourself. If you go to our “Books” page we have re-written most of our blurbs. I’m not suggesting they are perfect. In fact, I’m sure that Phoebe J Ravencraft would suggest some improvements if she were to read them. But they are different to our previous style. Just ask yourself one simple question – having read any of those, do you feel tempted to buy the book? More importantly, has our conversion rate for sales improved? We actually got an instant return for one book. The day we changed the blurb it got its first sale in months. Coincidence? Possibly, but we think it may have been the new blurb. Then a second book got its first sale in months, followed by a third. Too many for coincidence; this was a trend. I’m not going to pretend any of those books went from non-seller to best-seller overnight as a result of the tweaks we made - but “Fiction Blurbs: The Best Book Forward Way” paid for itself within a week and is still paying for itself in terms of sales. I highly recommend “Fiction Blurbs The Best Book Forward Way” by Bryan Cohen and Phoebe J Ravencraft. To find out more about the book, click here. Next week we’ll be reviewing another book which could help you to sell a lot more of your own books, so be sure not to miss our blog. In fact, why not sign up to our newsletter to make sure you don’t miss it. We’ll even send you a free ebook if you do. Just click the button below.

0 Comments

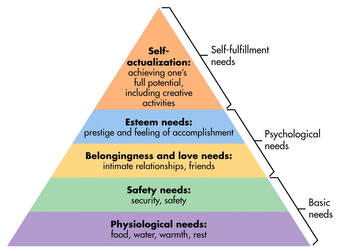

In last week’s blog we asserted that understanding a protagonist’s motivation was one of the critical factors in creating interesting characters for stories. In fact, we went further than that and said authors should be doing the same for antagonists as well. But in order to do that we also need to understand how and why motivation works in general otherwise we can’t attribute the right motivators for the correct reasons. For example, if our story involves a love triangle, what might motivate one of the characters to abandon their love in order to make the object of their love happy? In a selfish world like ours that makes no sense. But it is a well-used trope in romance. Which is what this week’s blog is about. It’s a whistle stop tour of motivational theory and what it can do for you as an author.  Motivation or Incentive? Motivation or Incentive? The first thing to understand is that there is a significant difference between motivation and incentive. The big difference between the two is that an incentive can never be enough for a person to place themselves in jeopardy. After all, there’s no point in being paid £1 million (an incentive) if you are going to end up dead and can’t spend it. But a person may take a dangerous, high paying job if it is the only way to provide security for the ones they love. Love is a motivation, money is an incentive. To put it another way, motivation drives us, but incentives can only pull us. In fiction we are always looking for what drives the character. The lure of wealth may be an incentive for a criminal, but it carries the risk of imprisonment. So, what motivates criminals to take that risk? Understanding that motivation makes the criminal far more interesting than just the lure of wealth, which is quite shallow.  Psychologist Abraham Maslow, the granddaddy of content based motivational theory. Psychologist Abraham Maslow, the granddaddy of content based motivational theory. Theories of motivation are generally grouped under one of two headings: content and process. Content theories focus on what things provide motivation and process theories focus on how motivation occurs. To add depth to a character it isn’t enough to know what motivates them (content) it is also important to know why (process). The two together provide layers of complexity and that makes characters more interesting. Abraham Maslow is the granddaddy of content theory. He theorised that in order to function at a higher level, you first required certain needs to be satisfied. In other words, you can’t create great art if you are starving to death. So, you have to have your hunger satisfied before you can achieve your goal to become an artist. This became known as a “hierarchy of needs”.  Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Maslow's hierarchy of needs. You may, at this point, be tempted to mention the name of Vincent Van Gogh, who only sold one of his paintings during his lifetime. But he wasn’t actually poor. He had a very well paid job selling art in his brother’s Paris gallery before he left to pursue his own artistic career. Van Gogh wasn’t penniless at the start of his career – though he may have been by the end. In practice this means that we are first motivated by a need to survive, but if that is secure we can then move on to be motivated by something at a higher level. In fiction this means that if a character is trapped inside a burning building, they aren’t going to be interested in catching the person that lit the match. Only after they have escaped the inferno will they turn their attention to that. A vagrant living on the street wouldn’t be motivated enough to help a damsel in distress, because their priority would be their own survival. But they can be incentivised to help the damsel because the incentive (usually money) secures their basic needs. However, if it looks like they may die in the attempt, the incentive would no longer be enough. They would need some other motive, such as love for the damsel. While good Samaritans may exist, they don’t place themselves in danger. They need motivation for that to happen.  GET MOTIVATED! GET MOTIVATED! As can be seen from that example, content based motivation is a tricky business and if you don’t understand those sorts of basics, your readers won’t believe in your characters. But notice the sorts of things that appear in Maslow's hierarchy of needs diagram from the third level upwards. there's plenty of stuff hidden behind those short statements with which you can play in order to provide your characters with motivation. But what content theory also makes clear is that what motivates us isn’t constant. Our motivation can change in response to circumstances. For example, we may be highly motivated to succeed in our careers, working long hours and totally immersing ourselves in our jobs. Then one day we meet the girl (or boy) of our dreams and suddenly our career isn’t the most important thing in our lives anymore. Winning the heart of the object of our desire is now what is uppermost in our minds, to the extent that we may throw away our career in order to be with that person. That, of course, runs contrary to Maslow’s theory, because if we lose our job we also lose our security. So, it appears that some motivators are more powerful than others, at least for some of the time.  Achievement and competition. Achievement and competition. Achievement and competition are theories of content motivation studied by David Mclelland. Today this is often portrayed in fiction as a negative thing; highly motivated achievers or competitors are often depicted as criminals or cheats, driven by their desire to win at all costs. Which is odd, because the sports stars we admire the most are highly motivated by competition and achievement. Not only do they compete in their sporting arena, they also compete off the field by consistently trying to beat their own best performances, in the gym for example. Name the sports star you admire the most and you are naming a highly motivated competitor, but modern fiction suggests you will also be naming a cheat. I think we need to change that stereotype with positive competitive role models in fiction. Is competition and high achievement a bad thing? That is for you to decide, but I know of one author who uses competition as a motivator for the success of his heroic characters.  Psychologist B F Skinner Psychologist B F Skinner When it comes to process theories, there is one that is usable in fiction. It is “reinforcement” theory, developed by B F Skinner. This is based on positive outcomes of certain types of behaviour. In fact this can be traced back even further, to Pavlov and his dogs, but Skinner is better known for his study of humans. If you can imagine a misbehaving child being given a biscuit in exchange for better behaviour, it will soon learn that if it misbehaves biscuits will be forthcoming, so that the reward becomes the motivator for bad behaviour. Extending that theory into adulthood, if a character believes that rewards come from bad behaviour they will continue to behave badly – which is great motivation for criminal characters. The opposite applies as well, of course. If good behaviour results in good outcomes, then a character is motivated towards good behaviour. It may also surprise them when their good behaviour results in a bad outcome, eg their loyalty being betrayed. That could be enough for a previously good person to start behaving badly. Because when we add emotions to motivation, we start to get a powerful mix. I have already mentioned the power of love to derail a career, but there are plenty of other emotions that can affect motivation. The most challenging question it is ever possible for an author to ask is what makes one man brave and another a coward. This is especially so in stories that involve death but can also be played out in terms of moral behaviour. Nature has given us three responses to danger: fight, flight or freeze. What makes one person choose to fight, another choose to flee and another to do neither (freeze)? Fear is a natural response to danger, so all three responses should be regarded as equal, because nature gave us the choice. But our regard for bravery and our contempt for cowardice shows that we don’t regard all three responses as being equal. Very often the individuals who take the actions can’t answer our question. Ask most decorated war heroes why they did what they did, and they are unable to answer, or they fall back on clichés like “duty”.  But duty only takes us so far. A soldier standing firm in the line of battle is doing his duty. A soldier that charges an enemy position in order to save a comrade is going far beyond that. It happens in real life, but quite rarely which is why medals such as the Victoria Cross and the Congressional Medal of Honour exist to recognise such actions. But in fiction it is the norm for the protagonist to exhibit that level of bravery and persistence. So, what can we give them, in emotional terms, so that they do that? And, more importantly, how can we create a backstory that shows how they developed that quality, based on what we know about motivation? This is where Skinner’s theory becomes important. If during their developmental years the character is rewarded for having beliefs and values that we admire, but isn’t rewarded for having beliefs that we detest, the qualities for which they were rewarded will become the motivators. They will also become the barriers when those qualities are undermined. The flawed protagonist is one whose beliefs and values are called into doubt by events, which cause them to question their beliefs and results in internal conflicts. The loner cop who drinks way too much whisky didn't start out that way. Something made them like that and the author gets to decide what it was. There is far more to motivation than I have had time to cover in this blog. I recommend further research. How much you include in a story is up to you, but layered characters with strong motivations are always going to be of more interest to readers than shallow characters who only respond to incentives. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  As publishers, we get sent a lot of books. But that’s OK because we’d be in trouble if people didn’t send us their books. It would be nice if I could say that all those books are great, and we can’t wait to be able to get them uploaded and out there with the reading public. Unfortunately, we can’t say that. I would estimate that perhaps 50% of what we are sent is never going to get published; not by us and not by any other reputable publisher, large or small. It usually takes us less than an hour of reading to make that decision. About half the rest start off well but then start to run out of steam, usually around the 30 to 40,000 word point. It was probably around that point that the author realised that writing a book wasn’t quite as easy as they had thought, but they kept ploughing on anyway, in the hope that something great would come out of it. Sadly, it didn’t, but it will take us maybe 2 – 3 hours to decide to pass on those books.  Finally, we get to the 20% to 30% of books that stand a real chance of finding readers. Those are the ones where we invite the author to work with us to try to get the book into its best possible version before we finally publish it. Some authors then pass, because they think their book is good enough already and doesn’t require our interference, or maybe they think they can get a better deal elsewhere (and maybe they can). But if a book is on our website it’s because the author has been more realistic and understands that all work can be improved, even if it is only a little bit. Just once in a while we get a book sent to us that we know from page 1 is going to be good. How do we know that? Because we get so absorbed in it that someone has to tap us on the shoulder and remind us that it’s time to pack up work for the day. Even then we’ll upload it onto a tablet so we can keep on reading it on the way home (but not if we’re driving). "Character = Conflict = Plot" Those books may be rare, but when we analyse what they have that other books don’t have, it usually comes down to just 3 things.

You will notice that I haven’t mentioned the plot. That’s because the plot is not the main driver of our engagement with the story. The protagonist and the problem(s) they face are what hooked us: character + conflict = plot. You will also notice that I mentioned the antagonist as being one of the 3 things that hooked us. Antagonists don’t get many mentions in blogs about writing and that’s a shame, because without an antagonist you only have half a story. Where would James Bond be without Goldfinger or Blofeld? Unemployed, that’s where. It is our contention (feel free to disagree) that a well-constructed antagonist is as important to a story as a well-constructed protagonist. For every Snow White, we need a Wicked Queen.  Think of Darth Vader. He starts off as the archetypal antagonist, just bad because he’s bad. But then we find out that he is Luke Skywalker’s father and, all of a sudden, he becomes much more interesting. He becomes so interesting that a considerable proportion of the next 3 Star Wars films are devoted to his “origin” story (Ep I: The Phantom Menace, Ep II: Attack of the Clones and Ep III: Revenge of the Sith). Yet time and again we get books submitted to us with antagonists so one dimensional we feel no emotional interest in them. We need to despise the antagonist in order to make it more important for the protagonist to succeed. But in those stories it is often like trying to despise Wiley Coyote or Elmer Fudd. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Number one in my list was the protagonist.  So, what makes a good protagonist? That will vary from genre to genre. For fantasy fiction they are required to be heroic, while for romance the first requirement is that they be attractive in some way (it doesn’t have to be a physical attractiveness). But that is just the surface level. The more complex the character, the more interesting they are. The more interesting they are, the more interest the reader will take in them. And the more interest the reader takes in them, the more likely it is that they will continue reading the book. It is very important that readers continue to read the book. If you are an Indie author, you need those readers to post favourable reviews of your book in order to sell more copies. And if you want to find a publisher, you have to submit a book that the publisher wants to finish reading.  Building complexity into a character, however, isn’t simple. It takes time and it takes an understanding of people. There are a few short cuts that can be taken, tropes as they are known, such as giving them secrets, but the thing that really catches the imagination is their motivation. Why are they doing what they are doing? After all, they could just as easily stay at home with their feet up reading a good book, like the rest of us. The reader has to believe that the protagonist is dealing with the conflict because they have a really strong reason to do so. But that leaves the reader with a gigantic “why” to be answered. And the only person who can answer it is the author.  Take Jack Reacher, for example. He is a drifter, a loner, and he doesn’t have to get involved in the problems of others. Yet he always does. He is motivated to help by a range of different things, depending on the plotlines, but the one that recurs most regularly is the desire to fight injustice in whatever form it appears. It may be the injustice of a small business owner having to pay protection money to gangsters, or it may be the injustice of the law not taking a victim seriously. It may be the injustice of the police being too incompetent to find the real criminals. It may even be the injustice of someone being wrongly accused of a crime. But whatever it is, it motivates Reacher to get involved when he really doesn’t have to. So, what motivates your protagonist to get involved when they don’t have to? And why does that motivate them so much?  Internal conflict is always good for adding layers of interest to a protagonist. That can be introduced in many different ways, from a lack of self-belief to questions about the morality of what they are doing. It is especially useful when internal conflicts start to impact on whatever goal the character is pursuing. Think about a vegan being attracted to someone who works in an abattoir – can you imagine the complexity of making that relationship work? It doesn’t always have to be as blunt as that example. In fact, subtlety often makes it more interesting, especially if the internal conflict is revealed slowly over the whole book rather than in one big lump, so that the reader says “Ah, now I see what the real problem has been all along”. To really get to grips with both motivation and internal conflict you have to research your character(s). Yes, I know you only just created them, but that doesn’t stop you doing “research” on them. All you have to do is ask the right questions – then answer them.  Dress your characters. Dress your characters. Start with their parents: were they loving, cruel, dismissive, encouraging or even absent? Parents are the first influence on a child and therefore the first to influence your character’s personality when they are older. From there you can move onto teachers, peer groups, young adulthood and the dreams and aspirations that come with it. For older characters, the age of Jack Reacher for example, you may want to continue that research into their 20s and even 30s. You dress your characters with their life experiences, their beliefs and their values the same way as you dress them in their clothes, and those things then provide their motivation and/or internal conflicts. If they fight injustice, then what is the injustice they suffered that makes them want to do that? If they are on a quest, what is it they are seeking to find out about themselves along the way? If they are afraid of starting a romantic relationship, what happened in their past that makes them so afraid now? I’m not going to ask all the possible questions; you are the author, they are your characters, you need to ask the questions. But the better the questions you ask, the better your characters will be.  And the same applies to antagonists. We are familiar with the surface level motives of antagonists: love, hate, jealousy, greed, lust for power, revenge, etc. But no one is born seeking revenge. No one is born jealous. No one is born lusting for power. So, what was it in their life that changed them and gave them those surface level motivations? What happened to make a “normal” human being want to rule the world?  You can throw in psychological motivations, such as psychopathy, sociopathy, narcissism megalomania, paranoia etc but even they require some sort of explanation. If you are going to use them you will need a good grounding in psychology and/or mental health so that you can understand what your antagonist’s backstory has to look like in order for them to suffer from those forms of psychological disorder. If you can come up with two complex characters (protagonist and antagonist), you are going to come up with a complex, layered conflict between them that holds the reader’s attention and has them crying out for more. And if you can come up with those 3 elements, you are going to find a publisher who wants to publish your book. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so. Disclaimer: We are not connected to Book Brush in any way other than as users of the product that has been reviewed. This review has not been paid for by Book Brush or by any other person or organisation.  This article is a review of the Book Brush app which allows authors to design their own book covers, rather than having to pay someone else a lot of money to do that for them. I have to say up front that some of the things that Book Brush allows you to do can be done just as easily in PowerPoint (if you are good at using PowerPoint) but, equally, some of the features are unique. And what is most unique as that it draws together everything you may need to be able to do under one URL. The service is provided on an annual subscription basis, charging at 3 levels: silver, gold and platinum. We paid for the silver level ($99, about £85) as that provided the things we needed right there and then (we knew we could upgrade later if we wanted to). Looking at the other two packages, it is hard to see them offering that much more – but on the other hand if it is something you want to do repetitively and you have no other way of doing it, you may regard the extra money as being well spent. I’ll cover the differences in the subscription levels a little later in this blog. "doing it myself was a no-brainer" The first thing I found useful was the introduction video that showed me how to use the app. I was able to watch it before I had even subscribed, and it persuaded me that what was on offer was going to save me money. Typically, we pay a designer on fiverr.com around $100 to provide us with an ebook and paperback cover package (with us providing the images to be used) and, as publishers, we may need a dozen of those each year, costing around $1,200. So, paying $99 a year and getting one of our team to do it was a no-brainer, providing we can create the sorts of designs that we want. How long does it take to design a cover?  Having watched the video and learnt the basics, and combining it with some use of PowerPoint (I’ll tell you why later) I was able to create a cover for the next Carter’s Commandos book in around 15 minutes. OK, the design isn’t complicated, but using the sorts of templates that are available within Book Brush, it wouldn’t have taken much longer to produce something more elaborate. I was able to do that after watching just one video and spending about an hour playing around with the various features. What’s more, I rather enjoyed doing it because the results are so easy and quick to see and it’s fun to be able to experiment with different designs. Warning to procrastinators: It is very easy to spend a lot of time playing with Book Brush while convincing yourself you are doing something productive. So keep an eye out and don't fall into that trap when you should really be writing. At the end of the process we know that by using Book Brush templates, our finished cover is going to be fully compatible with the technical requirements for KDP and other book publishing sites. But the biggest advantage is the range of templates that are available and how you can manipulate them to create a design that is unique to your book. The templates and other images are conveniently organised into genre specific groups.  KDP cover creator offers you about a dozen templates and they are pretty much fixed. You can add your own images, of course, but trimming them is difficult and it is inevitable that your book cover is going to look like hundreds of others, which is where Book Brush offers one of its great advantages. Not only that, but you have an almost unlimited ability to change colours and fonts. The platinum subscription for Book Brush offers the flexibility to remove backgrounds from images, but you may not want to pay for that. Removing background allows several images to be combined to create unique covers. Which is where PowerPoint comes in. If you know how to do it, you can remove backgrounds from images in PowerPoint, save the combined image as a .jpg and then import it into Book Brush ready to use. I’m not going to go into detail about how to do that in this blog. We searched YouTube and found this “how to” video for people who don’t already know. Along with all the templates Book Brush also has access to hundreds of thousands of free to use images which you can apply to your covers but, of course, you can also create or buy your own. They have a wide range of fonts and all the special affects you would expect to see for applying shadow, changing transparency etc. If you want to use a particular font and it isn't available in Book brush, you can import it.  There are also some blogs on the site that could be helpful to you, such as the one we read to discover what fonts work best for which genres and which should be paired together to differentiate between titles, sub-titles and author names. So, what more do you get if you upgrade? With the gold package you get templates into which you can insert your finished covers in suitable formats to use for your social media marketing, cover reveals etc, such as showing the cover in a Kindle frame with accompanying promotional text. That was about all I saw there that was different and not something that I considered to be worth paying for. With platinum you get the ability to create video trailers for your books, by combining either your own video images or using their collection of stock video. To that you can add music or a narration. The package is quite easy to use, can create videos compatible with the different social media platforms and the results look very professional. But it isn’t something we would use a lot so, in our opinion, it didn’t justify the additional $147 subscription fee.  If they offered the opportunity to buy a one-off video package for $10 - $15, we’d certainly use it, but I don’t think the subscription offers value for money unless you’re going to be creating a lot of video trailers. Where Book Brush really comes into its own is in creating paperback and hardback covers. With the wide range of trim sizes on offer through KDP and the wide variation of page counts between books, coming up with a PowerPoint template that works for every book is impossible, so it’s all down to trial and error, which can take hours of work to get right. But Book Brush just asks you how many pages your book has and then creates a custom template for you which is guaranteed to pass KDP’s quality standards. All you have to do is overlay the different content you want to use for your design and, again, you can use their designs and images or create your own. So, overall we are quite happy with Book Brush. It’s easy and quick to learn and you can start producing professional looking book covers within an hour of paying your subscription. We certainly recommend the silver package. Whether you want to pay more for the extra buzzers and bells is down to you. If you would like to know more about Book Brush, click/tap here. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, be sure not miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. We’ll even give you a free ebook for doing it. Just click the button below. It's New Year and we here at Selfishgenie Publishing are taking a well earned break.

But don't worry, our blog will be returning on Saturday 7th January 2023, so watch our socials for information on what we will be blogging about. In the meantime, we would like to wish you a very Happy 2023. And don't forget, books published by Selfishgenie are a great way to use those Amazon vouchers you got for Christmas. |

AuthorThis blog is compiled and curated by the Selfishgenie publishing team. Archives

June 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed