Picking a title for a book isn’t always easy. Sometimes the title picks itself, based on the plot or the leading character. But sometimes it isn’t quite so obvious. “Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit” by Janet Winterson, for example, isn’t a title that you might associate with a book about “religious excess and human obsession”, to quote from the book’s blurb. But it’s a best seller, so its readers obviously weren’t the type to be put off by an opaque title. However, is there more to it than just a having snappy title? What if you are publishing a collection of work that has been previously published. This happened to one of our authors, Robert Cubitt.  He had published a series of nine sci-fi novels under nine different titles, but the series collection was called, simply, “The Magi”. If anyone has read the book then that title makes sense, because the series is all about the search for the Magi, who are the rulers of the galaxy and they’ve gone missing. So far, so good. Each book in the series has its own title, but the first book gives the series its collective name. But what do you call the collection when you put all 9 books out under a single cover? Robert chose to call it “The Magi Omnibus”. It made sense to him, because an omnibus, as well as being a mode of transport, is a collection of stories either with a common theme or by the same author. So, tick the box on both counts. For the same reason the title also made sense to us. "sales started to tick upwards at once" But it turns out that not everyone seems to know that the word omnibus means a collection of work. The word has become old-fashioned, out of date. It also doesn’t resonate with non-UK readers. Robert’s generation grew up on the omnibus edition of “The Archers” broadcast on the radio every Sunday morning, which is all 5 daily episodes, each of 15 minutes duration, broadcast as a single 75 minute edition. There are also omnibus editions of some TV soap operas, such as Eastenders and Coronation Street. So, you would think that the term omnibus would be well known.  It appears we were wrong about that. While we weren’t looking, the omnibus has been replaced by the “box set”. And that was reflected in our sales for the collection. We were getting plenty of clicks on links to the book’s sales pages, but no buyers. We can only assume that potential purchasers were confused by the title, thinking it referred to the aforementioned mode of transport. So, we retitled it as “The Magi Box Set” to see what would happen. And sales started to tick upwards at once. It seems that the readers of sci-fi are happy to buy a box set, but they aren’t interested in buying an omnibus.  OK, lesson learnt. A title change can make all the difference in the world for some books. So, if your book isn’t selling, you might want to ask yourself what the title is saying to your potential readers. Ours was obviously saying “Radio 4” when we wanted it to say SYFY Channel or Netflix. This isn’t a phenomenon that is unique to the publishing industry. Plenty of films have been retitled because the original title didn’t go down well with test audiences, either at home or abroad. I’ll give you an example. The film “The Madness George III” was retitled “The Madness of King George” for the American market, because the producers thought that with so many films being released in series (eg Rocky, Rocky II, Rocky III etc), audiences might not go to see the film because they might think they’d missed The Madness of George I and II. Mad Max is a well-known film name these days, but very few people in the USA had seen the first film in the series, so when the second film was released in the USA it had a name change to “The Road Warrior” without any reference to Mad Max – and it worked  Will Smith in "Hancock" Will Smith in "Hancock" You may be familiar with “Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark” and if you are, you didn’t see it when it was originally released – or your memory is playing tricks on you. When it was released in 1981, it was just “Raiders of the Lost Ark” and was retitled later by George Lucas in order to fit in with the titling of the sequels, which did use the style “Indian Jones and ….” The Will Smith superhero movie “Hancock” (2008) didn’t start out with that name. It had the very generic title of “Tonight He Comes”. Would you have gone to see it with that title? It might have worked in the 1930s, but not in the modern market. So, if your book isn’t setting the reading world on fire, you might consider a change of title. But do include a note inside giving the original title, so people will know if they have already read it. No point in upsetting people by letting them buy the same book twice. Amazon gets a bit touchy about that too. Would you like a full-length eBook for free?* Of course you would. All you have to do is sign up for our newsletter to qualify. Just click the button. *Excludes "The Magi Box Set".

0 Comments

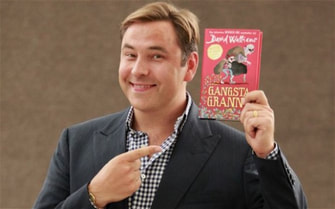

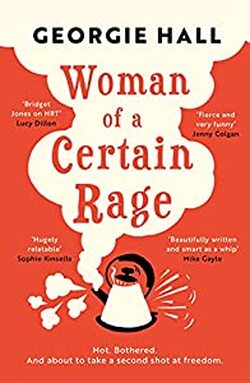

Why do so many authors suffer from “Imposter Syndrome”? It seems that every other Tweet or Facebook post that I see from authors doubts their ability to write, yet they are unlikely to choose writing as a career (or at least an ambition for a career) unless they actually are able to write in a coherent manner. I’m not talking about false modesty, or “humblebragging” as it is sometimes known, which I also see a lot of. That is a whole different thing. A typical humblebrag would look something like “I can’t believe it! I’ve just been asked for a full MS from an agent!” (the exclamation marks are typical of humblebragging punctuation). The use of “I can’t believe it” doesn’t make the brag about being asked for a full MS any less of a brag.  I’ve got nothing against the bragging part of it. If an author has been asked for a full MS by an agent, or has just signed a publishing deal, or has just sold the first copy of their book, then that is something worth bragging about. No, it’s actually the “humble” part I don’t like. The author isn’t fooling anyone with it. Own it, boys and girls; just own it. But imposter syndrome is something very different. Imposter syndrome is a feeling that successful people get that they aren’t worthy of the accolades that they are receiving. They feel that they don’t deserve it and that it has all been a big mistake and one day they’re going to get found out.  Most common amongst women and people of colour. Most common amongst women and people of colour. The term was first used by psychologists Pauline Clance and Susanne Imes in their 1978 research paper on the subject. They noticed that a lot of their female students seemed to feel that they didn’t deserve their places in college, even though they were more than capable. Their research was mainly conducted on women, who seemed to suffer a lot from imposter syndrome, possibly because women have historically had their abilities questioned (especially by men), so they have come to question it themselves. Later research found similar behaviour in people of colour for pretty much the same reason. More recent research has shown that anyone can suffer from imposter syndrome, but it is more common amongst women and people of colour. "But why do so many authors appear to suffer from it? " At its worst, imposter syndrome can lead to mental health issues because of the anxiety it causes sufferers. At its best it creates self-doubt, which is demotivating and it can lead to self-sabotaging behaviour, such as perfectionism. It doesn’t matter how many times people tell sufferers that they are good at what they do, imposter syndrome will always undermine any sense of achievement. But why do so many authors appear to suffer from it? There are a couple of reasons why we do suffer. One of the greatest is family and friends who don’t seem to think we have what it takes to write a book. They can believe in us as carpenters, plumbers, bank managers, marketing executives or whatever because we are, or were, employed as those. But you have to be special to be an author, right? Actually, no, you don’t have to be special, as any author can tell you. All you have to have is an idea, a basic sense of plot and character construction (both of which can be learned) and some basic written English skills.  You - an author? You - an author? But that lack of faith in us can undermine our own view of ourselves, especially if said friends and family haven’t actually read our books, so they continue to doubt us without having any evidence of our true capabilities. It goes back to the research carried out by Clance and Imes, where people (generally males) didn’t have faith in the capabilities of women, so women tended to absorb that lack of faith and reflect it back upon themselves. Just try being blond as well and see how much worse that feeling might be. But I think that the other main reason is that we are too ready to compare ourselves to the great figures of literature and we don’t feel we measure up well. And I think this stems from the way literature is taught in schools. This creates false comparisons.  In all professions there are leading lights; the great movers and shakers who change their industry or redefine their art in some way. Let’s keep away from writing for the moment and use music as an example. Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin and similar figures are held up as the benchmarks against which all other musicianship must be judged, or so we would be led to believe if our high school music teachers had their way. I’m not going to question the abilities of those composers, they were undoubtedly great, but that doesn’t mean that every other composer or musician isn’t also competent. Our orchestras are full of competent musicians, of which a few will be recognised as great soloists. Some might even earn the title of “Maestro” or “Maestra”. But that doesn’t mean the rest are bad. We can extend the argument into the realm of pop music. Lennon and McCartney wrote great songs and the Beatles were a great band. But that doesn’t mean that no one since has written a great pop song, nor that any band since wasn’t as good as The Beatles. By and large it is the paying public who decides which bands are great and which aren’t – not high school music teachers.  Just how much do I suck? Just how much do I suck? The same applies to literature. It is the book buying public that decides who is a “great” author, not English Literature tutors. The teachers can examine a book and tell you why it is well written and why it was hailed as a “classic”, but that is not the same thing as the author being popular. If it were, then Dickens and Twain would always be in the best sellers lists and no one would ever have heard of Dan Brown. If you only compare yourself to Charles Dickens, Mark Twain or Virginia Woolf, you may feel like an imposter. The same applies to modern writers. We’re not all going to win the Booker Prize or the Nobel Prize for Literature. But just because you aren’t spoken of in the same way as the winners doesn’t mean that you are unworthy of any success you may achieve. Stop beating yourself up, as the saying goes. If readers are buying your books and you are getting good reviews, it means you are a good writer. Enjoy that feeling.  Just because your books don’t make it into the Sunday Times (or New York Times) best sellers list, it doesn’t make you an imposter. You have to sell around 100,000 copies to make even the lowest entry into those lists and very few authors manage that in a year (about a hundred, in fact). So, if you only sold 90,000 copies, it doesn’t make you an imposter. And even if you only sold 1 copy, it doesn’t make you an imposter. All that means is that you haven’t yet been discovered and you need to do more marketing to get your books in front of the reading public’s noses. But above all you must remember that you chose to be a writer. No one puts a gun to an author’s head and makes them write. What made you choose to write was the desire to tell stories. And so long as you continue to tell stories, you will never be an imposter. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, be sure not miss future posts by signing up to our newsletter. Just click on the button below and you will also qualify for a FREE eBook..  In an earlier blog, a book review as it happens, I mentioned that I created a mental image of the sort of people that I think buy my books. It helps me if I have them in mind when I’m writing, because I can tailor my writing style to them. There is nothing new in taking this sort of approach. In marketing terms, it is P for people, which means understanding the sort of people who are going to buy a product. If you are creating fashions that appeal to women in their late teens to early twenties, for example, it is important to know what sort of styles, colours and fabrics those consumers are attracted to. It will be totally different to those that appeal to women in their 50s and 60s. Get it right and you sell lots of product, get it wrong and you are left with thousands of items unsold – and a reputation for being a brand that is out of touch.  Know your audience! Know your audience! I could give loads of examples of how manufacturers adopt this approach, but I would quickly bore you and I have no desire to do that. But market research plays a huge part in developing a product, just to find out what the buying public finds attractive and what they don’t. Pretty much every product has its “ideal” consumer. And, at the most basic level, a book is just another product, so knowing your audience, or consumer, is important to authors for the same reason. If you use a lot of modern slang in your writing, you are not going to write a book that appeals to readers for whom such slang is as alien as a foreign language. But there is more to it than that.  Sci-fi audience Sci-fi audience Certain types of fiction attract different types of reader. Research was carried out into readers of sci-fi and fantasy, collectively known as SFF. It was discovered that there is a strong correlation between people who take an interest in science and those who read SFF. The findings report that SFF readers start at a young age, typically under 20. They read more than the average number of books per month. Boys have a higher preference for sci-fi and girls have a preference for fantasy, though both are likely to read either. And perhaps most importantly, the study found that SFF readers have a higher level of educational achievement compared to other reading genres. The most important take-away from that is educated readers usually have more sophisticated tastes. They won’t put up with poor quality writing. So, if you are an author who writes in either of those genres, expect your readers to be well educated. They will have a good understanding of science and, for fantasy, they will probably have a good working knowledge of mythology, demonology etc "There are obvious age divides in some markets." If you forget that, you might find your books don’t attract readers and you may also find that those that do sell don’t get good reviews. Are you an SFF author? Did you know that? There are differences in other genres as well. Unsurprisingly, women are bigger readers of romance, but they are also bigger readers of thrillers, which came as a bit of a surprise to this author. Also, thriller and crime readers tend towards the older generations, with 35% being over 65, but less than 5% being under 30. So, in terms of the language used in thrillers and crime novels, it is best to stay away from modern idioms and slang if you want to reach the largest audience. There are obvious age divides in some markets. “Young adult” is such a market. Those readers will be well versed in modern slang. So much so that in three year’s time, a whole new audience will have emerged who can’t relate to the language that was used just a few years earlier.  Age gap Age gap This means that YA fiction dates very quickly, unless the author is very careful in their choice of language. It has to be “young” enough to appeal to that age group, but also won’t go out of date too quickly and result in poor sales in a few years’ time. YA readers outgrow the genre quite quickly, looking for new authors that appeal to their developing maturity, so there is no longevity, the way there is in other genres. Capture the attention of a thriller reader at 30 and you pretty much have their attention for the rest of their life. Capture a YA reader at 13 and you’ve probably lost them by 18. So, the YA author has to keep looking for the next audience, not just for their new books, but also for their existing books. Personally, I would avoid writing YA for that very reason, because the marketing effort is never ending. It also means that output has to be higher to satisfy the existing audience before they outgrow the genre.  Children's author David Walliams Children's author David Walliams This same problem also applies to writers of children’s books. If Mum or Dad were fans 15 to 20 years earlier, then they may buy the books for their children, but otherwise the author has to rely on a lot of peer influence to make their books popular. My grandson reads the books his school friends read, not the ones his parents want him to read. For example, The Chronicles of Narnia collection, by C S Lewis, rank only 5,600 on Amazon, but the latest David Walliams book is ranked at 13. In 20 years time you can say “David Walliams” and the children won’t reply “Yeah, I read his books”, as they do now, they’ll reply “Who?”. The author of the books they will be reading is probably still at school him or her self right now. So, who is your generic reader? Are they male, female or both? What age are they? What sort of educational levels have they achieved, or will they achieve? What are their hobbies and interests? What language will they relate to and what will make them throw your book at the wall? It isn’t always easy to answer those sorts of questions, but you can start close to home. Do you write the sorts of books that you also like to read? If so, then you probably conform to the norm for your genre except for, perhaps, gender. Just because you are male (or female) it doesn’t mean that only men (or women) will like your books, because some genres have cross gender appeal. Others, however, don’t.  Some men won’t buy books with a female protagonist and some women won’t buy books with a male protagonist, because they can’t identify with them. Others have no problem with either. And if there are gender issues that limit your audience size, then you can bet your life that there are also further limiting factors, such as sexual preferences. Will a book with strong LGBTQ+ content have a wide appeal amongst heterosexual audiences? It's more like to be read by a niche audience and niche markets are unlikely to result in fame and fortune (if those are your goals). Ultimately this is important not just in terms of who will buy your books, but also how you market your work. There is no point in directing your limited advertising budget towards the wrong audience, or one that is heavily biased in terms of gender, age, educational achievement or any other characteristic. It also matters when it comes to where you promote your work. If you are a writer of children's books or YA, don't bother with Twitter or Facebook, because your readers are all on Tik-Tok. As for the older generations, the older they are, the less likely they are to be on social media in the first place. Reader loyalty doesn’t come about by accident. It comes about because you understand your readers and your readers understand your books. If you have enjoyed this blog and want to be sure of not missing the next one, just sign-up for our newsletter by clicking on the button below and you will also qualify for a FREE eBook..  When I sit down to write a book, I have a very clear picture in my mind regarding the person who is going to buy and read it. OK, it has to be a bit generic, but I know their probable gender, their typical age range and the sorts of interests that they have. I try to write in a way that will appeal to them specifically. As a multi-genre author, I have several of these images, to suit my different target audiences, but I won’t go into details about them now. I’ll save that for another blog. But my point is that if author Georgie Hall also creates a mental image of her target audience, I doubt she would have imagined me. Which is a pity, because her book, “Woman of a Certain Rage”, should be read by all men of a certain age. At any time, half the population of the world is either going to go through the trials and tribulations of the protagonist, Eliza Hollander, they are actually going through them or they have been through them already. If men who are in a relationship with women were to read this book, it might help them to understand their partners better and it may also help to save a few relationships.  But I’m guessing that this book was aimed mainly at women of a certain age and will mainly be read by them. As I said before, that’s a bit of a pity, made even more so by the fact that it’s a very enjoyable read, says a man of a certain age. Eliza Hollander is fifty and is suffering the rigours on menopause. The use of that word alone will probably send male readers rushing towards their man caves with their fingers in their ears and singing "la la la" to keep the noise out. But if you are male and still reading, I encourage you to continue. Eliza once had ambitions to become a great actress, until life got in the way and she had to settle for a lesser career. She still practices her art, but not on the grand stage she once imagined. Her relationship with husband Paddy is strained, for many reasons. The triggering event for the book is a simple one, which many readers might relate to. Her beloved dog died. The dog’s unquestioning devotion helped to mask the cracks that had opened up in Eliza’s life and now she is forced to face them at the same time as she is having to deal with the menopause and all that goes with it. "Eliza is made of sterner stuff" Eliza has three children: Joe who is a student activist, Summer an A Level student and wannabe social media influencer who is suffering a teenage crush on one of her teachers and Ed, who suffers from autism, which brings along its own problems. Throw into this mix the family from hell (well, purgatory at least) and an amorous Italian restauranteur and you have the cast list for a delightfully humorous and touching novel. But Eliza is made of stern stuff. She wants to fight back against the aging process and “make a difference”, just as she had planned to do when she was a young actress in the late 80s. Like many women of her age, Eliza feels she has become invisible and wants to be seen as a person once again. So while the backdrop of the book may be the menopause, the foreground is very much Eliza’s fight to get her identity back, at the same time as she saves her marriage.  A narrowboat, not a barge, but also a vehicle for a metaphor. A narrowboat, not a barge, but also a vehicle for a metaphor. It helps if, as a reader, you have a liking for narrowboats (or barges as they are sometimes incorrectly called) but that isn’t essential. The narrowboat in question is just a vehicle (groan) to help carry a larger metaphor. I won’t go into detail but “The Tempest”, as the narrowboat is called, plays a pivotal role in the story for several reasons. It also helps to have a liking for the writings of Shakespeare but that, too, isn’t essential. The book is well paced and it is very easy to engage with the likeable Eliza, who tells her story in the first person. Starting the book I was unsure that it was really something that I would enjoy, but a couple of chapters later I found that I was wrong about that. Despite the difference in gender and the biological issues that creates, I was able to relate to quite a lot that Eliza was describing. In between narrating the current plot, Eliza goes back and tells us what her earlier life was like and that provides plenty of light and shade for the story. These passages are memories, not flashbacks, and make it easier to understand how Eliza drifted into the unsatisfactory state in which she now finds herself.  What does the future have in store for you? What does the future have in store for you? So, an engaging and entertaining book which works on several levels. If you are female and under forty, read this to find out what life has in store for you. If you are female and over forty, it may help you to know that you are not alone and if you are male and in a relationship with a female in either of the aforementioned groups, then this will help you to prepare for what might lie ahead. I just hope it doesn’t send you running for the hills in fear, because your partner will need you, probably more than at any other time of her life. I highly recommend “Woman of a Certain Rage” by Georgie Hall. To find out more about the book, click on the cover image at the top of this blog. If you have enjoyed this blog and/or found it informative, be sure not to miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. We promise not to spam you. Just click on the button below and you will also qualify for a FREE eBook.. And if you would like to be a guest book reviewer for the Selfishgenie blog, please contact us to find out how.

Just 3 rules: 1. You can't plug your own work (though we may give it a mention in our introduction), 2. We don't pay and 3. We reserve the right not to publish any review. |

AuthorThis blog is compiled and curated by the Selfishgenie publishing team. Archives

June 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed