|

For the next few weeks we are featuring blogs by guest bloggers on a wide range of subjects related to reading and writing. All the opinions expressed are those of the blogger and are not endorsed by Selfishgenie Publishing. Enjoy!  The circus is in town and a wizened little man goes into the big top during rehearsals and approaches the ringmaster. “I’ve got an act and I want to join the circus.” “Ok” says the ring master. “Show me what you’ve got.” So the man goes into the ring and climbs the tent pole all the way to the top. When he gets there he lets go and stretches out his arms and starts to flap them. He then proceeds to fly round the inside of the big top, doing loop the loops and barrel rolls, swooping and soaring, all the time flapping his arms for all he’s worth. After five minutes he settles gently onto the ground in front of the ringmaster once more. “What do you think?” The little man asks. “Is that it? You do bird impressions?” Boom boom. My apologies to the long running TV series M*A*S*H for stealing that joke. But did you laugh at it? If nothing else, it does show you how up to date my TV viewing is these days.  The reason I ask is that comedy in the written word is very hard to do. What one person finds amusing will pass over another person’s head and may be misinterpreted completely. Stand-up comedians spend hours practicing in front of test audiences above pubs and in tiny comedy clubs making sure their material works before they unleash it on their target audience, whether it is in a larger comedy club, at The Edinburgh Fringe or in the 02 arena. A writer doesn’t have that luxury. If he gets it wrong then it could cost him his audience forever. It’s a one-shot deal. The writer may have an editor that may question the suitability of a joke, its comic value, its relevance to the plot and so on. What appeared hilarious when being written in the solitude of the author’s kitchen may fall as flat as a pancake when it reaches the editor’s desk. So what does the writer do? Do they trust to their instinct and go for the laughs, or do they play safe and keep the story serious? Is there room for both?  Another problem is that it’s tough to sustain comedy over a long period. A stage comedian works at a rate of two or three laughs a minute. Story telling comedians may string a joke out for three or four minutes before getting to the punchline. So how many jokes does the writer need to put into a story to give it that humorous feel? Is it one per page? One every thousand words? One per chapter? Let’s say it’s the latter. My books generally run out at about 25 chapters. Some have more and some less. At the rate of one significant joke per chapter the sums are easy enough. 25 jokes for a stand-up comedian, therefore, is about ten minutes worth of material. Perhaps half the duration of a comedy club slot. That’s a lot of jokes and every one of them has to hit the mark. Of course, not all the humour in a book has to be in the form of joke. Some of it can be situational. The writer gets a lot of leeway in this area, painting pictures of absurd characters or giving them funny things to do or say. The writer can make his characters do silly things. He can make them stupid to the point of imbecility. He can make them accident prone. He can make them pompous or self-important. But he still has to maintain the humour for over 80,000 words (that’s about the acceptable minimum length for a novel these days). That’s a lot of jokes to have to write. Name one well known writer who is noted mainly for the humour in his novels. Difficult, isn’t it? There are plenty who write short pieces for newspapers and magazines. The now defunct Punch magazine was known for them. But ask them to extend that to a full-blown novel and you would start to see the panic in their eyes.  There have been some, of course. Terry Pratchett managed to achieve this in many of his works, but not all of them by any means. The late Keith Waterhouse wrote Billy Liar and I’ve already mentioned M*A*S*H, which made three outings as books for Richard Hooker (real name H. Richard Hornberger). Twelve others in the franchise were ghost written by William E Butterworth and were less critically acclaimed because of it. But when we talk about humorous writing we are often talking about satirical works or parodies, rather than books that are intended solely to be funny. I’ve read a few books recently which, according to their “blurbs” on Amazon, were laugh a minute works. I have to say that they generally failed to make me laugh. The jokes often descended into slapstick and that is a visual media, or it became very juvenile in nature, which is not the sort of comedy that will appeal to an adult reader. More often the jokes were non-existent. So, as someone who likes to introduce a lighter note into my books, that makes me a little bit nervous. What if my readers don’t get the jokes?  I’ve hedged my bets a bit by not claiming that my books are funny. That way at least I’ll be managing expectations. But that is a double-edged sword. A lot of the time we laugh at jokes because we know they’re jokes and we’re waiting for the punch line. If they were told in a more serious tone of voice with no comedic preamble, would we automatically laugh? Maybe, but maybe not. Like most people I have preferences when it comes to comedy. I laugh at some comedians more readily than I will laugh at others. We all know that humour is a very personal thing, as evidenced by the joke I started with. Some people will have laughed and others won’t. That makes life difficult for an author, because they need to appeal to their entire readership, not just to the few people who will understand their humour. So, humour in a novel is fraught with difficulty, for both the writer and the reader. All I can say is that if you find yourself laughing at my books then the jokes were intended. If you don’t laugh then the book is a serious work of fiction and therefore not the place for me to start telling jokes. Either way I hope you enjoy them. Would you like to be a guest blogger for Selfishgenie? Just email us with your idea for a blog. The address is on our "Contact" page. Did you enjoy this blog, or find it interesting? To be sure of not missing an edition, just sign up to our newsletter. We'll even send you a free eBook for doing it. Just click the button below.

0 Comments

For the next few weeks we are featuring blogs by guest bloggers on a wide range of subjects related to reading and writing. All the opinions expressed are those of the blogger and are not endorsed by Selfishgenie Publishing. Enjoy!  It was one of those conversations that only happen in pubs when drink has been taken. They usually don’t make sense the next day and are quickly forgotten. Well, usually they’re quickly forgotten. The subject was fantasy fiction. You know the sort of thing: wizards, orcs, elves, dragons, enchanted swords etc. My friend said he didn’t read that sort of book because he wasn’t able to suspend his disbelief. I was duty bound to argue against him because… well, because we were in a pub and that’s what blokes do when they’ve had a pint or two. But then, afterwards, I thought about it a little bit more. Why would it not be possible to suspend disbelief and read fantasy fiction?  We suspend our disbelief every day of the week over some matter or other, particularly when it comes to the sorts of thing politicians say. So what’s so hard about suspending one’s disbelief over a story that is to be found on the fiction shelves? No one is saying its true (well a few deranged people maybe, but I’m not going to count them). All we fantasy fans are saying is that it’s an escape from the real world and into another. The stories are as valid as they are in any other genre. Indeed, they can be found in genres other than fantasy. They usually take the form of a battle of good against evil, during which quests are undertaken or duties carried out. Honour is high on the agenda, as is bravery, selfless devotion and many other altruistic character traits. Perhaps this is what’s wrong. Perhaps these things are so lacking in our modern world that some people can’t believe that they might exist in any world. There is an old tradition of fantasy fiction, of course, though it isn’t always recognised as such. First, we go all the way back to the Ancient Greeks and Homer’s epic stories in the Iliad and the Odyssey. These may be based on some factual events, but they also contain a lot of fantasy.  Then we have Arthurian legend. Now, on the surface we have a story about men battling against evil, which forms the core of many a good novel. But we also have a wizard (Merlin), a witch (Morgana), a magical sword in a stone (Excalibur), a mysterious lady in a lake (Viviane or Nimue) and so on. In its basic form it’s no more fantastic than Tolkien. After that we get to the legend of Robin Hood. There is no evidence that he ever existed and what few historical bits of evidence that suggest someone resembling him did exist, don’t portray a picture of the hero of the medieval peasants that robbed from the rich to give to the poor, but a petty criminal who robbed from anyone and kept the loot for himself. OK, more of a legend than a fantasy, but one we buy into. There may be no dragons or orcs, but they’ve been replaced by the Sheriff of Nottingham and his men. We mustn’t forget the Daddy of them all William Shakespeare. In his plays we have a ghost in Hamlet, another one in Macbeth along with three witches, in The Tempest we have a fairy and some sort of troll (Caliban) and of course A Midsummer Night’s Dream which is littered with fairies and in which Bottom is given a pair of donkey’s ears, as though that were normal.  Charles Dickens isn’t averse to using ghosts if it suits his purpose, as he shows in A Christmas Carol, while Bram Stoker gave us Dracula and Mary Shelley provided us with Dr Frankenstein’s hand-built monster. None of these books or plays were aimed specifically at children, which is where my friend thinks the target audience for most fantasy fiction lies. Ghosts, vampires and monsters may be seen as belonging to the horror genre, but they appear in fantasy as well. Now, I’m probably going to upset a few diehard fans here, but I’m going to suggest that the great British Hero James Bond is no more believable as a character than Bilbo Baggins. What is my justification? I hear you ask (I have good hearing). Let’s look at the evidence. Cars that turn into submarines, wristwatches that contain lengths of garrotte wire, cars with ejector seats and so on and so forth. But that’s all boy’s own gadgetry and no more of a fantasy than a sword that glows blue when there are orcs around. At the time when Ian Fleming wrote the stories, the technology for those gadgets didn’t exist, but that didn’t stop him fantasising about them.  But the real fantasy is Bond himself. A suave, debonair killer who’s also a babe magnet and can get into a fight with half a dozen Kung Fu masters and walk away leaving them in a crumpled heap. He’s been shot so many times he must resemble a colander. He’s fallen from trains, planes and ski slopes. While Ian Fleming and the writers who continued the franchise never claimed magical powers for Bond, does this not require just as much suspension of disbelief as it does to read about Gandalf? Bond may not have “One Ring to rule them all (etc)”, but that was because Q never quite got round to finishing it (But just wait for the next movie – you read it here first).  There is, of course, another literary genre that is just as fantastical and requires just as much suspension of disbelief. I mean Sci-Fi. People who will gladly suspend disbelief to accept the premise of strange creatures inhabiting worlds far from our own are sometimes reluctant to do the same for stories containing wizards and dragons. Why? Science does suggest that life may exist on other planets. Indeed, it’s been said that it would be a strange universe if life didn’t exist on other planets. However, science has no idea what form it may take and what its capabilities might be. This is the space that the sci-fi writer inhabits, if you’ll pardon the pun. The space where anything is possible providing the author doesn’t actually ignore the laws of physics. But sci-fi writers do that all the time as well. Time travel, warp speed, sub space, hyperspace, dilithium crystals. Do these sound familiar? Which ones are made up and which does science accept as being possible? No I don’t know either. Dilithium does exist, you can Google it, but can you use it to power a space ship? So, where’s the difference between fantasy and sci-fi? Why is one believable to my friend but the other not? So where do you stand on this issue? Do you read fantasy novels? If not, can you tell me why you don’t? Just comment below. Would you like to be a guest blogger for Selfishgenie? Just email us at our general enquires address, which can be found on our Contact page and tell us what your blog would be about. If you enjoyed this blog, or found it interesting, then be sure not to miss future editions by signing up to our newsletter. We'll even send you a free eBook when you do. Just click the button.

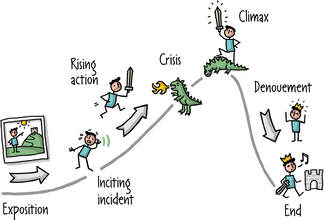

Pricing your book – is it an art or a science? I’m not asking you to pick a side; I’m only offering an opinion. Take it or leave it, but before you make up your mind, you have to understand two things. First of all, there is the economics of pricing. Then there is the psychological aspects of pricing; what assumptions do people make when they see a price tag on a product? Let’s start with the economics of pricing. If you are a big publishing house, there is a lot you have to pay for before the product (book) goes on sale. First off there are the publishing rights for the book – what the author wants for selling his or her soul to Mammon. Many new authors won’t get that, they’ll just be offered royalties based on sales. But a bestselling author can charge a hefty fee up front for giving a publisher exclusive rights to their next book - or even several books.  Then there is the cost of editing and proof reading in order to get the book into the best possible version of itself. Add to that cover design, printing and distribution and the publisher has already invested a considerable amount of money that must be recouped. Then there is the cost of marketing, because nobody is going to buy a book if they don’t know it exists. Finally, there are all the “back office” costs that must be recouped: HR, accounting, IT, rent, utilities, etc. What are known as “overheads” but without which no business functions efficiently. Put that all together and there is a lot of money to be recovered and publishers want their money back quickly, because they have shareholders who want a dividend at the end of the year. Consequently, publishers price high because they know that once a book has been out for a while, people lose interest in it because there are other, newer titles coming out all the time, so they must cover their costs and generate a profit in the shortest possible time.  All that marketing is aimed at getting the book into the best-seller list as quickly as possible, so that sales gain some “momentum”. Readers are more likely to buy a book if they think that a lot of other readers have already bought it and that is what the best-sellers list tell them. And there was you, thinking that the best-seller list followed sales, when they are really leading them. So, when you see a book with a list price of, perhaps, £20 ($22) for a hardback, £13 for a paperback and maybe £12 for the Kindle version, all that stuff is what you are actually paying for – not the words on the page. The author will probably receive less than 10% of the sale price for each book and their agent takes a cut of that, reducing it further (are you still sure you want to be published by a big publishing house?).  But you are an “Indie” author. You don’t have all those costs to meet before your book goes on sale and you don’t have to recover them quickly in order to satisfy shareholders. You can charge what you like. Therefore £5 for a Kindle version and maybe £8.99 for a paperback doesn’t seem unreasonable. You aren’t greedy – so as long as you make some money from your book, you are happy. Well, you may need to rethink that a little bit. You really need to market your book if you want it to sell and if you want to sell more than a handful of copies, you may need to spend some money on marketing. That means pitching your price at a level that will allow you to cover the marketing cost. Either that, or you will have to settle for a smaller slice of the cake.  But what about the psychology of pricing? What does the reader infer from the price at which you sell your “product”? Unsurprisingly, there have been books written on the subject. I’m not going to name any as I haven’t read them, so I don’t know if they are any good. But if you are interested, Google “Psychology of book pricing” and they’ll show up in the results. But I did find this blog by Thomas Umstattd Jnr, written in 2020. For a start, Umstattd reminds us that price is so important that it has been included as one of the “P”s of the marketing mix. That means it has to be taken seriously as a subject in its own right.  But the real issue on book pricing is what the reader compares the price to. Let’s imagine that it takes 10 hours to read a book. What else could the reader do for 10 hours, and how much would that cost? That is the comparison that readers make when they buy a product. They mentally say to themselves “If I spend my money on this, would it give me as much fun as spending my money on something else?” This is called “anchoring”. They anchor the price they are willing to pay to read your book against the cost of another type of entertainment (or another product) and form an opinion on how good a bargain it is by comparison. If they are browsing books on Amazon or in a bookshop, you are already halfway to winning the sale, but there is still a choice to be made – your book or someone else’s. That suggests that the lower the price you set, the better comparison and the more books you will sell.  But, of course, the anchor point is only part of the story. Because you have to tell your readers that, whatever comparison they are mentally making, your book is going to represent better value. You have to guide them into making that decision because, otherwise, they may conclude the opposite and not buy your book. Umstattd describes a number of ways you can use your marketing ‘copy’ to influence readers into perceiving that your book represents good value for money. I won’t repeat them here but, intuitively they seem to be good suggestions. But readers don’t just want something to read, they want to read a “good” book; in other words, they want quality. The price should indicate to the reader that they are getting that. It means that setting a low price isn’t always a good strategy.  But at the same time, readers will want someone else to tell them that your book is good, so the reviews have to justify the price. If you are only getting 3 star (or lower) reviews, then you can’t charge a premium price for your book because readers won’t believe they are getting “quality” because other readers are saying they aren’t. If you aren’t getting any reviews at all, then you are really in trouble. And if the reader is paying a higher price for the book thinking it is a quality product, then the content has to match the price. It goes without saying that the story has to be excellent. It also has to be well edited, free from typos and grammatical errors and the cover design has to be more than just the basic offerings chosen from the KDP menu. If they aren’t getting that interior quality, the chances of selling other books to the same reader are slim. There is a way of making money by setting a low price and that is to write a lot of books. There are readers who will accept a loss of quality (even in the storytelling) in return for a cheap read. Making 10p a copy on 5,000 book sales is more profitable than making £1 per copy on 100 sales. And you get the bonus of there probably being more reviews posted about the books.  But that is a decision that you have to make for yourself. But you don’t have to make it blind. If you have beta readers, one of the questions you can ask them is how much they would have been prepared to pay on Amazon to read the book if they’d had to purchase it. You will get a range of responses, but you can average them out to give you an indicative price. This blog, on the AuthorImprints website, also takes a look at how to price your books and offers some indicators. One thing seems clear, if you are just starting out, selling your book cheaply in order to generate reviews seems to be a recommended strategy. Once your books gain in popularity and gains positive reviews, you can always increase the price to improve your royalties.  Then there is the 99p (99c) “special”. KDP allows you to reduce the price of your book for up to 5 days, providing it is subscribed to KindleUnlimited. That can be used, in conjunction with advertising, to generate sales because people are more inclined to say “why not give it a try?” at that price. This is especially good if you write a series of books. By heavily discounting the price of Book 1 of the series, people are more likely to by Book 2, 3 etc if they enjoy it. And you have nothing to lose, because if your book isn’t selling then reducing the price makes no difference because 100% of nothing is still nothing. And, finally, there is the “freebie”. I’m not talking about giving your life’s work away for free, just letting people have a taster of what they could get if they buy your life’s work. The freebie is usually a prequel or other introduction to the main series of books. Giving it away for free is a way of generating interest in the main series. But be warned: the freebie must be of at least the same quality as the full book, because even if people are getting it for free, they will still be judging you as an author and you can’t risk that judgement coming back negative. But if the reader likes your freebie, they may buy the book and give it a try. I can say from personal experience that I have bought books off the back of free ones. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative (hopefully both) and want to be sure not to miss the next edition, just sign up for our newsletter by clicking the button below. And we’ll even send you a free book for doing it.  In a recent blog I made a statement to the effect that there were only 7 basic plots for books. It appears that I was right. Experts think that there are seven basic plots for books. I would throw in an 8th, but I’ll get to that later. The idea was developed by someone called Christopher Booker, who carried out research across a wide selection of books and then published his results in a book (what else) entitled “The Seven Basic Plots: Why We tell Stories”, published in 2004. This was no passing fancy. It took him 34 years to write. Amongst his other credits is that he was one of the founders of Private Eye magazine. He has nothing to do with the Man-Booker Prize which is awarded for literature.  As well as the 7 basic plots, Booker came up with the idea of the meta plot, that is the basic structure which the majority of books follow. This breaks down into four distinct phases. Phase one is the call to action, in which the protagonist is drawn into the adventure to come. Some go willingly, like James Bond, while others, like both Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, go less willingly. Phase two is the frustration stage, where the protagonist struggles against the forces arrayed against him (or her) in order to resolve the problems he is faced with and win the day. During this stage they discover their weaknesses, which they must overcome and also, usually, unexpected strengths. In the nightmare phase all hope is lost and all seems to be doomed. The protagonist may come close to death and is certainly in despair, though quite how this works for plot type 5 (see below) I’m not sure. Finally, we reach the resolution stage, where the protagonist, against all odds, wins the day and earns the title of hero. Again I’m not so sure that this works for plot type 6 (also see below). It doesn’t matter how many other characters there are in the book, it is with the protagonist that the reader’s thoughts and emotions ride. If he or she doesn’t succeed, then the story doesn’t succeed. Even if the protagonist dies at the end, their death must be a sacrifice to gain their success. Do you recognise those four phases from the books you read or write? I must admit that I find it hard to think of any book that doesn’t conform to that pattern So, what are the 7 basic plots that Booker identified?  Plot 1. Overcoming the monster. This might be a real monster, such as the Minotaur favoured in Ancient Greek literature, or it may be a figurative one: Big Business, Corrupt Government, Rogue CIA agent, etc. A lot of Greek literature focuses on battling monsters, but it has stood the test of time. H G Wells used it in War Of The Worlds and Michael Crichton in Jurassic Park. The ‘monster’ is also present in stories such as George Orwell’s 1984 and the Jason Bourne and Jack Reacher books. Just because it doesn’t have horns or a tail it doesn’t prevent it being a monster. Plot type 1 is, of course, a staple of the horror story genre: Frankenstein, Dracula, Halloween, Friday The Thirteenth. However, I used it in my World War II series, Carter’s Commandos, where the monster is the Nazi regime in Germany.  Plot 2. Rags to riches. The most obvious (for me) examples are Dicken’s Great Expectations. Aladdin, The Prince And The Pauper etc. First of all the protagonist comes into great wealth before losing it all and then having their fortunes restored after they have learnt a significant lesson. There is usually a moral to the story, especially around hubris and not abandoning one's real self.  Plot 3. The quest. This is much loved by the writers of fantasy novels and I used it in my Sci-Fi series. With the search for the magic sword, or whatever, also comes personal growth. The protagonist never comes out of a quest unchanged in some way. Its origins are as distant as Homer’s Iliad and progress through history with A Pilgrim’s Progress, Lord Of The Rings, Watership Down, etc.  Plot 4. Voyage and Return. Similar, in some ways, to the quest, the protagonist must leave his home in order to achieve something and, again, returns changed in some way. One of oldest versions of this is Homer’s Odyssey, but perhaps the best known of these is the Lord Of The Rings prequel The Hobbit. Other examples include Gulliver’s Travels and The Wizard of Oz. It is the principal feature of this genre that the protagonist isn’t (necessarily) financially enriched by the journey, but is spiritually enriched.  Plot 5. Comedy. Is this really a plot in its own right, I wonder? Comedy can be inserted into almost any plot, even a tragedy if it’s handled correctly. That’s why we refer to “black comedies”. The protagonist is usually a light, cheerful character to whom life frequently hands the dirty end of the stick: a good person to whom bad things happen. However, they stumble along and emerge triumphant at the end, often through luck rather than judgement. Mr Bean or any Norman Wisdom film provides examples.  Plot 6. Tragedy. In Ancient Greek theatre this was the partner of comedy as the Greeks only did two types of theatre. Again, I would dispute this being a plot in its own right. Most stories can include a tragedy or two. The protagonist either has a major character flaw which they are unable to identify in themselves or they commit an act for personal gain which has unforeseen consequences and which spirals out of control. Either way it doesn’t end happily. There are many stories that fit this genre: King Lear, Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, Bonnie and Clyde, Anna Karenina. This isn’t so popular in modern fiction and film as the public prefers a happy ending, so nowadays the inherent tragedy turns to success in the final chapter. While it was always normal for the protagonist to die at the end of a tragedy it is far more normal, now, for them to live. Not only will they live, they will also get the girl (or boy).  Plot 7. Rebirth. This is the plot for any story in which a villain or an unlikeable character ends up as the hero. It involves the protagonist going through an experience that changes them radically in some way, making them a “new” person. There can also be an element of this in some of the other plots, particularly 3 and 4. Here we find A Christmas Carol (not my alternative version), Beauty And The Beast and Despicable Me. Now we come to my additional plot, Plot 8: Romance. Boy meets girl, boy loses girl for some reason (OK, girl can also lose boy), boy and girl either struggle to get back together, or fight against the inevitable attraction, and finally get back together again at the end of the book (and, of course, there are LGBTQ+ equivalents). This is the territory of Mills and Boon and Barbara Cartland, but has been used by many other authors. In which other genre would Pride And Prejudice fit?  Now, here is the challenge. Can you think of any book that doesn’t fit into one of those 7 (or 8) categories? I have tried and I can’t think of any. If you are an author, have you ever written a book that doesn’t fit into any one of those categories? Would you ever try? An interesting thought is that we might each be living our lives in one of those ways. In other words there are only 8 life stories. That sounds a bit scary, as we all consider ourselves to be unique in some way. However, much as that idea both scares and appeals to me, I have no evidence to back it up so I’ll leave it there. What is of considerable interest to me is this idea of change. The majority of the plot lines described require some form of change to be undergone, in order for there to be a happy ending. This is where the story and real life part company. As a species we aren’t good at changing. If we were we wouldn’t keep repeating the mistakes of the past that lead us into all sorts of messes, up to and including war.  This is where the author often views life through rose tinted spectacles. Their protagonist always undergoes the change, however reluctantly, whatever it is and grows with the experience. In real life this so rarely happens. I’m not saying that it doesn’t happen, because some people really do undergo change, though not always for the better. But for most of us life goes on the same day after day as we curse our bad luck rather than changing our behaviour as a result of experience. So, if there are only 7 (or 8) basic plots for books, why do we keep buying books? After all, once we have read one book from each plot type we have read them all, haven’t we? Well, this is where the skill of the author comes in. He or she makes us believe that their story is both unique and original. "It is the author that makes the difference." Firstly, they will mix and match the plot types to give variation to them. As I suggest above, a quest can also be a journey, and frequently is. Sling in a romance and a bit of personal growth and you tick the boxes of another two types. However, that still limits the number of stories available (Just over 40,000 by my calculation). Yet literally millions of books have been written. It is the author that makes the difference. The skilful author makes you believe, through his or her mix of character and plot, that their story is unique. All the great authors have done this. It is called “finding one’s voice”, in other words saying something different. It is hard to say which authors will find their voice and which will never be heard, because this is down to the reader to judge. But what is clear is that if the reader wishes to find a new voice to listen to they won’t find it by reading what everyone else is reading. A new voice can only come from a new author. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, why not be sure not to miss future editions. Just sign up for our newsletter - and you can get a FREE ebook as well. Just click the button. |

AuthorThis blog is compiled and curated by the Selfishgenie publishing team. Archives

June 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed