Understanding a protagonist’s motivation is one of the critical factors in creating interesting characters for stories. In fact, we will go further than that and say that authors should be doing the same for antagonists as well. But in order to do that we also need to understand how and why motivation works in general otherwise we can’t attribute the right motivators for the correct reasons. For example, if our story involves a love triangle, what might motivate one of the characters to abandon their love in order to make the object of their love happy? In a selfish world like ours that makes no sense. But it is a well-used trope in romance. Which is what this week’s blog is about. It’s a whistle stop tour of motivational theory and what it can do for you as an author.  The first thing to understand is that there is a significant difference between motivation and incentive. The big difference between the two is that an incentive can never be enough for a person to place themselves in jeopardy. After all, there’s no point in being paid £1 million (an incentive) if you are going to end up dead and can’t spend it. But a person may take a dangerous, high paying job if it is the only way to provide security for the ones they love. Love is a motivation, money is an incentive. To put it another way, motivation drives us, but incentives can only attract us. In fiction we are always looking for what drives the character. The lure of wealth may be an incentive for a criminal, but it carries the risk of imprisonment. So, what motivates criminals to take that risk? Understanding that motivation makes the criminal far more interesting than just the lure of wealth, which is a shallow incentive.  Psychologist Abraham Maslow Psychologist Abraham Maslow Theories of motivation are generally grouped under one of two headings: content and process. Content theories focus on what things provide motivation and process theories focus on how motivation occurs. To add depth to a character it isn’t enough to know what motivates them (content) it is also important to know why (process). The two together provide layers of complexity and that makes characters more interesting. Abraham Maslow is the grandaddy of content theory. He theorised that in order to function at a higher level, you first require certain needs to be satisfied. In other words, you can’t create great art if you are starving to death. So, you have to have your hunger satisfied before you can achieve your goal to become an artist. This became known as a “hierarchy of needs”. You may, at this point, be tempted to mention the name of Vincent Van Gogh, who only sold one of his paintings during his lifetime. But he wasn’t actually poor. He had a very well paid job selling art in his brother’s Paris gallery before he left to pursue his own artistic career. He wasn’t penniless at the start of his career – though he may have been by the end.  Maslow's Hierarchy Of Needs Maslow's Hierarchy Of Needs In practice this means that we are first motivated by a need to survive, but if that is secure we can then move on to be motivated by something at a higher level. In fiction this means that if a character is trapped inside a burning building, they aren’t going to be interested in catching the person that struck the match. Only after they have escaped the inferno will they think about that. A vagrant living on the street wouldn’t be motivated enough to help a damsel in distress, because their priority would be their own survival. But they can be incentivised to help the damsel because the incentive (usually money) secures their basic needs. However, if it looks like they may die in the attempt, the incentive would no longer be enough. They would need some other motive, such as love for the damsel. While good Samaritans may exist, they don’t place themselves in danger. They need motivation for that to happen. As can be seen from that example, content-based motivation is a tricky business and if you don’t understand those sorts of basics, your readers won’t believe in your characters.  But what content theory also makes clear is that what motivates us isn’t constant. Our motivation can change in response to circumstances. For example, we may be highly motivated to succeed in our careers, working long hours and totally immersing ourselves in our jobs. Then one day we meet the girl (or boy) of our dreams and suddenly our career isn’t the most important thing in our lives anymore. Winning the heart of the object of our desire is now what is uppermost in our minds, to the extent that we may throw away our career in order to be with that person. That, of course, runs contrary to Maslow’s theory, because if we lose our job we also lose our security. So, it appears that some motivators are more powerful than others, at least for some of the time. Achievement and competition are theories of content motivation studied by David Mclelland. Today this is often portrayed in fiction as a negative thing; highly motivated achievers or competitors are often depicted as criminals or cheats, driven by their desire to win at all costs. Which is odd, because the sports stars we admire the most are highly motivated by competition and achievement. Not only do they compete in their sporting arena, they also compete off the field by gaining more public acclaim. In modern fiction, the highly motivated competitor that you admire so much would be portrayed as a cheat, because that is the trope that fiction writers use. Competitiveness = negative character traits.  Psychologist B F Skinner Psychologist B F Skinner Is competition and high achievement a bad thing? That is for you to decide, but I know of one author who uses competition as a motivator for the success of his heroic characters. When it comes to process theories, there is one that is usable in fiction. It is “reinforcement” theory, developed by B F Skinner. This is based on positive outcomes of certain types of behaviour. In fact, this can be traced back even further, to Pavlov and his dogs, but Skinner is better known for his study of humans. If you can imagine a misbehaving child being given a biscuit (cookie) in exchange for better behaviour, it will soon learn that if it misbehaves biscuits (or cookies) will be forthcoming, so that the reward becomes the motivator for bad behaviour. Extending that theory into adulthood, if a character believes that rewards come from bad behaviour they will continue to behave badly – which is great motivation for criminal characters. The opposite applies as well, of course. If good behaviour results in good outcomes, then a character is motivated towards good behaviour. It may also surprise them when their good behaviour results in a bad outcome, eg their loyalty being betrayed. That could be enough for a previously good person to start behaving badly.  Because when we add emotions to motivation, we start to get a powerful mix. I have already mentioned the power of love to derail a career, but there are plenty of other emotions that can drive motivation: fear, jealousy, hatred, greed, disappointment, pleasure, etc. The most challenging question it is ever possible for an author to ask is what makes one man brave and another a coward. This is especially so in stories that involve death but can also be played out in terms of moral behaviour. Nature has given us three responses to danger: fight, flight or freeze. What makes one person choose to fight, another choose to flee and another to do neither (freeze)? Fear is a natural response to danger, so all three responses should be regarded as equal, because nature gave us the choice even if we don’t make it consciously.  But our high regard for bravery and our contempt for cowardice shows that we don’t regard all three responses as being equal. Very often the individuals who take the actions can’t answer our question. Ask most decorated war heroes why they did what they did, and they are unable to answer, or they fall back on cliches like “duty”. But duty only takes us so far. A soldier standing firm in the line of battle is doing his duty. A soldier that charges an enemy position in order to save a comrade is going far beyond that. It happens in real life, but quite rarely which is why medals such as the Victoria Cross and the Congressional Medal of Honour exist to recognise such actions. But in fiction it is the norm for the protagonist to exhibit that level of bravery.  However, the brave person isn’t unafraid. The brave person is one that overcomes their fear. But what motivation is so powerful that it able to make people face down their fear and do incredibly dangerous things rather than running away? So, what can we give them, in emotional terms, so that they do that? And, more importantly, how can we create a backstory that shows how they developed that quality, based on what we know about motivation? This is where Skinner’s theory becomes important. If, during their developmental years, the character is rewarded for having beliefs and values that we admire, but isn’t rewarded for having beliefs that we detest, the qualities for which they were rewarded will become the motivators. They will also become the barriers when those qualities are undermined. The flawed protagonist is one whose beliefs and values are called into doubt by events, which cause them to question their beliefs and results in an internal conflicts. There is far more to motivation than I have had time to cover in this blog. I recommend further research. How much of that you include in a story is up to you, but layered characters with strong motivations are always going to be of more interest to readers than shallow characters who only respond to incentives. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.

0 Comments

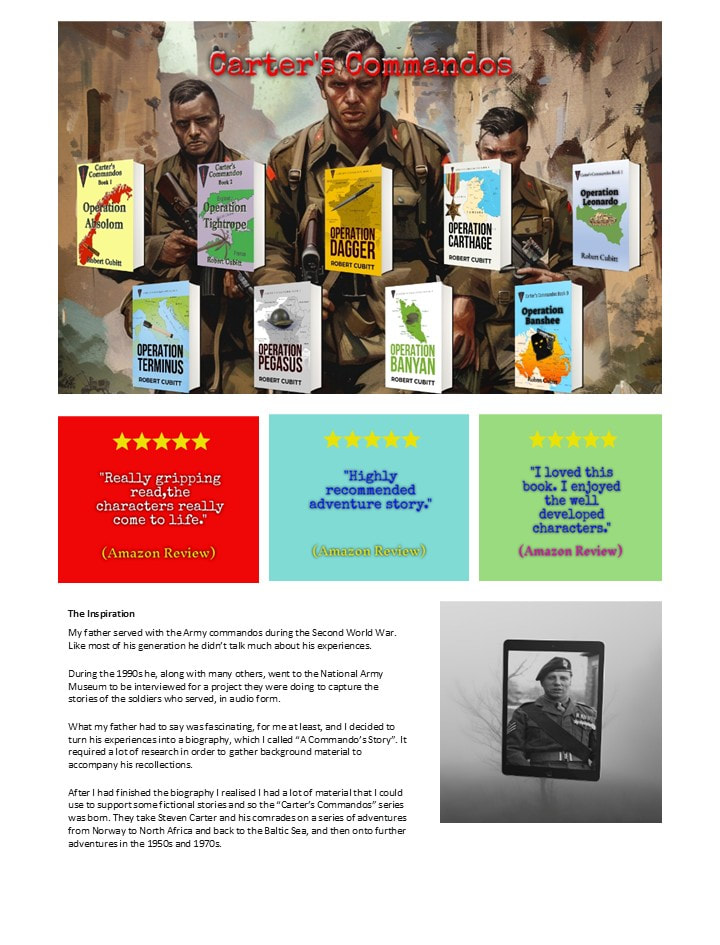

This week I want to address an issue about audiences for books and what we really mean by that word. First of all, a little story to provide context. On Facebook, someone posted an idea recently that they were considering. They write true crime stories and were thinking of engaging with a YouTube creator who makes videos about true crime, thinking that a review or endorsement would help their book sales. The YouTuber has a large following, so, on the surface, it looks like a winning idea. Several responses came back saying it was a good idea, because both the author and the YouTube creator were targeting the same audience. I disagreed with that view at a fundamental level. I believe they were targeting totally different audiences. Yes, both audiences are interested in true crime, but that doesn’t make them the same audience.  YouTube is a video medium. It targets people who like to watch videos. To use the marketing term, that’s the way they “consume” their entertainment. True crime authors, however, are targeting their work at people who consume their entertainment in written form, primarily books. Looking at a Venn diagram of the two audiences, there is an overlap where people who like true crime will consume their entertainment in both video and written form. However, it is the size of that overlap that determines whether or not it is worth spending money on the idea, because the YouTuber will probably want to be paid for their endorsement. Readers often seek in depth knowledge, enjoy imaginative story telling and have a keen interest in diverse genres. YouTube viewers prefer visual content, quick tutorials and enjoy entertainment videos.  It is important to remember that just because people like the same genre, they won’t also use the same medium to consume it. Let me take you away from books for a moment to illustrate my point. Everyone has to eat but we don’t all consume food in the same places. Some people like take-out food. Some like going to fast food outlets. Some like to cook at home and some like to eat in a restaurant with waiter service. Despite all of them eating food, in marketing terms each of those groups (and there may be others) are all different audiences. Marketing companies spend a huge amount of time and money to make sure that their advertising is seen by the right audience. They consider TV, radio, newspapers, magazines, internet sites and a whole range of other ways of advertising to decide which is going to be best for them. For example, you won’t see adverts for McDonalds in the pages of The Times – but you will in the Sun. That’s because Sun readers are more likely to eat in McDonalds and Times readers are more likely to eat in regular restaurants. They all eat food, they may even all eat burgers, but they are not the same audience. And yes, we know that some McDonalds customers will sometimes eat in restaurants and some restaurant customers will sometimes go to McDonalds - but they are the overlap in the Ven diagram - a small proportion of each audience.  That is why Amazon advertising is so effective compared to other advertising channels. Readers go onto Amazon to find books. They may not buy them there, they may buy them in bookstores or through other websites, but they use Amazon for “product research”. So, if you advertise on Amazon, your ad will be seen by people who read books and you don’t have to worry about whether or not they also watch YouTube videos.. The audience for books, regardless of genre, is always the people who read books. Any other type of entertainment consumption is just a distraction and trying to use it for marketing is likely to cost you more than it earns you. It is why none of the book marketing gurus recommend advertising on YouTube. If it was an effective channel for selling books, they would be all over it. And if it isn’t good for selling books, then there is no point in paying a YouTuber to endorse your book – no matter how large their following. Similarly, mainstream publishers don’t use YouTube for marketing. If it was an effective channel, they too would be all over it. So, our key take-away from this blog is that just because two groups of people like the same subject, it doesn’t mean they are the same audience. You have to consider the preferences for how they consume their entertainment, just as restauranteurs have to consider how different groups of diners choose to consume their food. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, make sure you don’t miss future instalments by signing up to our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook if you do.  I’d like to start this week’s blog by asking you to use your imagination for a moment. Imagine you are at a book fair and a potential customer stops in front of your table. They pick up your book, examine the front cover and then turn it over to read the back matter. Then they raise their eyes and are clearly going to speak to you. “Did you write this?” they ask (they always ask that for some reason, that or “are you the author”?). “Yes.” you reply. “Is there anything you want to know about it?” There then follows a conversation about the book, which can take too many forms for me to cover all possibilities. But one question that is often asked is “What inspired you to write this book?” This is the solid gold question. If you can answer that, you have an almost certain sale. Readers love to know the “origins” story of a book. Not the origin in the way “Batman Begins” is an origins story. This is the origin of the idea, the inspiration that caused the book to be written.  But on Amazon (and other retail sites) you are unable to tell that origins story that increases the likelihood of making the sale. Except that you can tell the story. This blog is about how you can tell it. You might think that you could include it in your blurb. But that is not effective. Readers rarely read all the way to the end of a blurb. After 200 – 300 words they are either interested enough in the book that they stop reading or are so disinterested they are already scrolling through the search results looking for something else. Those latter readers are lost to you, so we can dismiss them for the purposes of this blog (though why they are disinterested is the subject of lots of blogs about blurb writing). The trick now is to turn interested readers into buyers. They are the person stood in front of your table at the book fair asking about how your book came to be written. But they are viewing the book on Amazon, so how can you answer that question?  Finally, we get to the point of this blog, which is that you use A+ Content. This is exclusive to Amazon and Amazon claims that using A+ Content increases conversions to sales by up to 10%. In terms of ad clicks, that’s one extra sale for every 10 clicks. Those extra sales alone could pay for the ad. We have blogged about using A+ Content in the past, so this is something of an update based on what we have learnt since then. First of all, what is A+ Content?  It is space on your Amazon sales page that you can use to provide additional information about your books. There are several ways of using it and different types of sellers will use it in different ways. You have probably seen A+ Content when you have shopped on Amazon and not even been aware of it. You can insert graphics, graphics and text, product comparisons and all sorts of other stuff. But the key thing for this blog is that you can provide that “origins” story. The wordcount is limited, so you have to be brief, but a good writer can pack a lot into very few words. A+ Content is inserted as “modules”. Each module is a combination of graphics, text and other elements that allow you to provide the additional information. In addition, you can add keywords to the graphics, so the measly 7 sets of keywords that KDP allows you for your books is now capable of being multiplied. You can use up to 5 modules. The type of content we are about to describe uses 3 modules, but don’t let that limit you. If you can think of ways to use 5 modules, then use 5 modules. Below is the total display we used for one of our books. We’ll talk you through each module below it. The top module is the attention grabber. It is the sort of thing we use in our ads, so some of our potential readers may already have seen it. As you can see, it makes it clear that the book we are trying to sell is part of a much longer series, which appeals to a lot of readers. Below the main graphic we have used a module that inserts 3 images side-by-side. Each image features a quote from reviews of the book. We created these as images so we could make them stand out more than just using plain text. Reviews are known to be a critical part of the “sales funnel” because good reviews stimulate a desire in the reader to read the book. Our 3rd and final module is the one we think is doing the heavy lifting. It is where we tell the “origins” story. It is an image on one side (it can be either left or right) along with accompanying text which we have headlined “The Inspiration”. You don't have to use an image, of course, but we think that adds greater interest as images draw the eye to the text. It is this final module that will turn interested readers into buyers. Yes, they may still scroll down the page to see more reviews. Yes, they may still go to the “free sample” to read the opening chapter(s). But mentally they have already bought the book if they like the “origins” story that goes with it. Just an FYI, when the Amazon page is viewed on a phone, the A+ Content is usually the first content to be seen, so you can get a strong message across even before the reader gets to the blurb.  How do you upload A+ Content onto your page? Go to your KDP bookshelf and select “promote and advertise” from the drop-down menu to the right of the book (3 dots). On the marketing tools page, look for “A+ Content”. Select the marketplace for your book (you can use different content for different Amazon territories) and then go through the various steps to select and insert the modules you want to use. I suggest you read the KDP tutorials on A+ Content before you start if you want to avoid wasting time, because the process isn’t as intuitive as KDP’s designers would like to think. You can find more information here. A+ Content If you want to use A+ Content on both an ebook and paperback page, you have to create it twice, once for each ASIN. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, make sure you don’t miss future instalments by signing up to our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook if you do.  Why do so many authors suffer from “Imposter Syndrome”? It seems that every other post on X (formerly Twitter) or Facebook post that I see from authors doubts their ability to write, yet they are unlikely to choose writing as a career (or at least an ambition for a career) unless they actually are able to write in a coherent manner. I’m not talking about false modesty, or “humblebragging” as it is sometimes known, which I also see a lot of. That is a whole different thing. A typical humble brag would look something like “I can’t believe it! I’ve just been asked for a full MS from an agent!” (the exclamation marks are typical of humblebragging behaviour). The use of “I can’t believe it” doesn’t make the brag about being asked for a full MS any less of a brag. I’ve got nothing against the bragging part of it. If an author has been asked for a full MS by an agent, or has just signed a publishing deal, or has just sold the first copy of their book, then that is something worth bragging about. No, it’s actually the “humble” part I don’t like. The author isn’t fooling anyone with it. Own it, boys and girls; just own it. But imposter syndrome is something very different.  Imposter syndrome is a feeling that successful people get that they aren’t worthy of the accolades that they are getting. They feel that they don’t deserve it and that it has all been a big mistake and one day they’re going to get found out. The term was first used by psychologists Pauline Clance and Susanne Imes in their 1978 research paper on the subject. They noticed that a lot of their female students seemed to feel that they didn’t deserve their places in college, even though they were more than capable. Their research was mainly conducted on women, who seemed to suffer a lot from imposter syndrome, possibly because women have historically had their abilities questioned, so they have come to question it themselves. Later research found similar behaviour in people of colour for pretty much the same reason. More recent research has shown that anyone can suffer from imposter syndrome, but it is more common amongst those two groups.  At its worst, imposter syndrome can lead to mental health issues because of the anxiety it causes sufferers. At its best it creates self-doubt, which is demotivating, and it can lead to self-sabotaging behaviour, such as perfectionism. It doesn’t matter how many times people tell sufferers that they are good at what they do, imposter syndrome will always undermine any sense of achievement. But why do so many authors appear to suffer from it? There are a couple of reasons why we do suffer. One of the greatest is family and friends who don’t seem to think we have what it takes to be an author. They can believe in us as carpenters, plumbers, bank managers, marketing managers or whatever, because we are, or were, employed as those. But you have to be special to be an author, right? Actually, no you don’t have to be special, as any author can tell you. All you have to have is an idea, a basic sense of plot and character construction (both of which can be learned) and some basic written English skills, which can also be learned. But that lack of faith in us can undermine our own view of ourselves, especially if said friends and family haven’t actually read our books, so they continue to doubt us without having any evidence of our true capabilities.  But I think that the other main reason is that we are too ready to compare ourselves to the great figures of literature and we don’t feel we measure up well. And I think this stems from the way literature is taught in schools. This creates false comparisons. In all professions there are leading lights; the great movers and shakers who change their industry or redefine their art in some way. Let’s keep away from writing for the moment and use music as an example. Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin and similar figures are held up as the benchmarks against which all other musicianship must be judged, or so we would be led to believe if our high school music teachers had their way. I’m not going to question the abilities of those composers, they were undoubtedly great, but that doesn’t mean that every other composer or musician isn’t also competent. Our orchestras are full of competent musicians, of which a few will be recognised as great soloists. Some might even earn the title of “Maestro” or “Maestra”. But that doesn’t mean the rest are bad. We can extend the argument into the realm of pop music. Lennon and McCartney wrote great songs and the Beatles were a great band. But that doesn’t mean that no one since has written a great pop song, nor that any band since wasn’t as good as The Beatles.  False Comparisons False Comparisons The same applies to literature. It is the book buying public that decides who is a “great” author, not English Literature tutors. Teachers can examine a book and tell you why it was well written and why it was hailed as a “classic”, but that is not the same thing as the author being popular. If it were, then Dickens, Austen and Twain would always be in the best sellers lists and they aren’t and many popular authors would never have been heard of. If you only compare yourself to Charles Dickens, Mark Twain or Jane Austen, you may feel like an imposter. The same applies to modern writers. We’re not all going to win the Booker Prize or the Nobel Prize for Literature. But just because you aren’t spoken of in the same way as the winners doesn’t mean that you are unworthy of any success you may achieve. Stop beating yourself up, as the saying goes. If readers are buying your books and you are getting good reviews, it means you are a good writer. Enjoy that feeling.  Just because your books don’t make it into the Sunday Times (or New York Times) best sellers list, it doesn’t make you an imposter. You have to sell around 100,000 copies to make even the lowest entry into those lists and very few authors manage that in a year (about a hundred, in fact). So, if you only sold 90,000 copies, it doesn’t make you an imposter. In fact you were a great success. And even if you only sold 1 copy, it doesn’t make you an imposter. All that means is that you haven’t yet been discovered and you need to do more marketing to get your books in front of the reading public’s noses.  But above all you must remember that you chose to be a writer. No one puts a gun to an author’s head and makes them write. What made you choose to write was the desire to tell stories. And so long as you continue to tell stories, you will never be an imposter. Instead of beating yourself up, why not celebrate what you have achieved? Because you have done what only a few thousand people in the world will ever do. You have written a book. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, make sure you don’t miss future instalments by signing up to our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook if you do.  Many an “Indie” author will tell you that the hard part of being an author isn’t the writing of the book, no matter how hard that seemed at the time. No, the hard part is actually selling the book so someone can read it. Let’s face it, it doesn’t matter how good the book is, if no one knows it exists then they can’t buy it. Readers rarely, if ever, just stumble across a new author’s work. The book may occasionally appear on Amazon in search results, but that is the equivalent of hoping to hit a fish by throwing a stone into the sea. If the book has no sales history, it will be so far down the results that you would need a submarine to reach it. We have published many blogs on book marketing, but we thought it might be timely to reiterate the key messages.  We’ll start with the marketing mix – the 6 Ps. Some marketing blogs talk about the 4Ps, but we’re a bit like Spinal Tap, our Ps go all the way up to 6 (younger readers may not get that reference). These are:

You might think that ’promotion’ is the most important part of the marketing mix, but it isn’t. It’s people. You can promote your ‘product’ as much as you like, but if you aren’t reaching the right people, then you are wasting your time and, probably, your money. For this reason we are going to discuss each of those Ps in the order we think is of most importance.  The most important “people” is you. It is your knowledge of marketing which will sell books and it is your lack of knowledge that will hold you back. So, the most important thing we can say at this point is to invest in your “people” and learn how to do it properly. You don’t have to undertake a 3 year marketing degree course, but you do need to learn. There are free courses on FutureLearn and there a lot of books on book marketing available. Invest in yourself before you spend money on paying others to do things for you. The rest of your ‘people’ are the people who read books similar to the ones you write. They are the ones you need to identify and engage with on social media. I say ‘engage’, because if you just ‘promote’ you will lose their interest very quickly. Yes, you can promote, but only as a small part of engagement. You need people to want to follow you, which means having something interesting to say. And if you doubt that, consider this – you’re reading this blog, aren’t you? That is part of our ‘engagement’ with you. Paying companies to blast out posts about your book won’t get you sales -despite their promises of having a gazillion followers. Because only the posts that reach the sort of people that read your sort of books are of any use and only you can identify and engage with those people.  We’ll assume from the start that your book is well written, has a good plot, interesting characters, has been properly edited, proofread and corrected. It is therefore fit for purpose. Only you and your Beta Readers can judge that. So that part of the next P, ‘product’, is OK. After that the most important part of the product is the cover. Despite the warning in the old proverb, people do judge books by their covers. So, yours must be right for your genre. A picture of a woman in a big bonnet walking through a field of daisies isn’t going to sell many sci-fi books. That cover image is what is going to attract people’s attention, so it has to be eye catching and genre appropriate. The second thing about the cover is that it should tell the reader a little bit about what is happening in between the covers. Call it a visual representation of the plot. A picture is worth a thousand words, or so they say, so make sure that the picture on your cover is using those thousand words to best effect.  What about price? How much should you charge for your book? If you are a big-name author, you (or, more likely, your publisher) can get away with charging £13.99 ($15.99) for your book. If you are an Indie author, don’t even think about it. There is some interesting psychology related to pricing. On the one hand, people expect to pay more for a quality product. On the other hand, everyone loves a bargain, even readers. Where you pitch the price of your book is therefore important. Price it at 99p (99c) and readers may think "It can’t be very good if they’re practically giving it away". On the other hand, price it at £13.99 and readers may say "I’m not going to pay that much to read a book by an author I’ve never heard of". We price our ebooks at £4.99 - £5.99 ($5.99 - $6.99) and that seems to be about right for us. But the key messages are (a) don’t undersell yourself and (b) don’t price yourself out of the market. There are times when you can price at 99p, but those are for promotional purposes. That shouldn't be your basic price.  When we talk about ‘place’ we mean the places where you promote your books rather than the places you sell them. We’re going to assume that your book is listed on all the relevant websites and, for those of you that don’t want to give money to Jeff Bezos, all we can say is that if you aren’t on Amazon, you aren’t anywhere. Internet searches always place Amazon at the top of the results, so if someone is actually trying to find your book, that is where it will appear first – and perhaps the only place on the first page of results. But in our terms, place means your choice of social media site(s) on which to engage with readers and your choice is important. If you want to reach young people, then Facebook isn’t the place and X (aka Twitter) is iffy at best, because young people are always on the newest, trendiest platforms. Only 51% of social media users between ages 12 and 18 use Facebook – the second smallest group.  So, you need to do some basic research to make sure the platform(s) you are using are the right ones to reach your target audience. But don’t rely on social media alone. Local newspapers and radio stations are always looking for content, so a short item (written by you) will fill some column inches for them or an interview will fill five minutes of radio time. But, again, don’t expect them to find you. You have to reach out to them. Also, check your local community resources (libraries, schools, churches, clubs, societies, etc) for events where you can go along and talk about your work (and maybe sell a few copies). One thing about newspapers and other media – don’t pay to go chasing it. If it is offered, great, but the sales it brings aren’t worth the money you have to pay PR people to get it for you.  Promotion can be anything from a Facebook post to a video, podcast, a free extract or paid for advertising. I don’t aim to cover all of those. Instead I’ll focus on the one that you have to pay for – advertising. Social media (and Amazon) has given us all the ability to run relatively cheap advertising campaigns. But which ones work depends on the advertising channel you use. There is no point in paying for an advert on Facebook if hardly any of your target audience ever uses Facebook. We can tell you where we get the best return on our advertising investment – but that would be more confusing because we use different platforms for different books, because different audiences use different social media platforms. What we can tell you is that each platform (including Amazon ads) has its peculiarities when it comes to advertising. Whether it’s how you use keywords, what images you use, what text you use to accompany the images, etc are all different on different sites. It pays to advertise but you have to know how to advertise on each specific platform you use in order to get the best results.  You have to learn to use each site. There are myriad books on the subject and videos on YouTube. Read and watch before setting up your first ad and you may save yourself a lot of money and heartache. Test your ads before you commit a large budget to them. A few £ or $ spent running a test can save you a lot more in the longer term. One tip we will give you is that Google Ads don’t seem to work. Not for us and not for the gurus we have consulted. Google Ads may be great for some types of product, but they don’t seem to work for books. But one important detail about advertising. Make sure your advert includes the following:

You’re now wondering what I’m going to say about ‘process’. Actually, not a lot. I’ve tried to get the messages in this blog in the order you need to address them. That’s about all the ‘process’ you need to worry about at the moment. But if you want to be successful your ‘process’ must also include research:

Without that research, you may as well be standing on a street corner shouting ‘buy my book’. And you will be no more successful. And, if doing research sounds like too much hassle, then good luck getting people to stumble across your book by chance. If you have found this blog informative or entertaining (or both) then make sure not to miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for joining. Just click on the button below. |

AuthorThis blog is compiled and curated by the Selfishgenie publishing team. Archives

June 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed