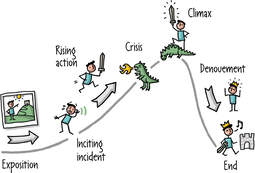

Having a great idea for a story is one thing, turning that idea into a book that people want to read all the way to the end is something else. Countless books end up as DNF (did not finish) and attract poor reviews because the author couldn’t keep their readers interested enough in what was happening for them to stay the course and finish the book. And a book that ends up as DNF means that its reader won’t buy the author’s next book. Then you have the books that readers did finish but didn't like, which also attract poor reviews. So, 10 simple tips to make sure your book doesn’t share that DNF fate and attracts good reviews. They aren’t complicated, but they do need to be at the forefront of the author’s mind as they write.  1. Invest time in your character building People engage with characters, not plots, so the characters are the most important part of writing. A good protagonist (or MC if you prefer) isn’t what is visible from the outside. It is what is on the inside that counts. We may be attracted to a person by their looks and style, but we fall in love with them because of who they really are, even making allowances for their flaws. In real life we don't fall in love with shallow people, so why would we do it in books? Create a pen picture for all your major characters. Start by giving you character a back story, beginning with their family and home life, through their education, their peer groups and their life experiences. These things shape their values and beliefs and those are the things that direct their behaviour. Your character has to behave consistently, in accordance with their values and beliefs. They may be forced by circumstances to “act out of character” at times, but that always creates a dilemma for them and is a source of internal conflict (see below). Above all give them emotions, so that readers feel those emotions and reflect them in their reading experience. If your character is moved to tears, your readers should be moved to tears too. If your character is laughing, your reader should also be laughing. You may not use a lot of the material that you generate in your pen pictures, but knowing how characters will behave in any particular set of circumstance means they can behave consistently over a lengthy story.  2. Create a meaningful conflict. Character + conflict = plot. The conflict that faces your protagonist is what the story is all about. No matter what the conflict is, they have to resolve it by the final page in order to complete the story and fulfil the destiny you create for them. Conflicts come in many different disguises and will depend very much on the genre in which you write. It can be the character’s internal struggle to overcome their own demons, or it can be an external struggle to overcome actual demons. Every story, even a comedy, is about overcoming conflict. But whatever the conflict is, it has to be of interest to the reader, so it has to be larger than life and something that readers are unlikely to experience for themselves, which makes it interesting for them  3. Create a meaningful consequence Failure to resolve the conflict has to have consequences, otherwise it is hard to inject drama into the story. The more severe the conflict, the greater must be the consequences of failure. In romance, failure may end with a broken heart. In a court room drama failure may end in imprisonment or financial ruin. In action adventure the consequence of failure is almost always death and/or destruction. Whatever the consequence, it has to match up with the reader’s own fears because that is what will keep the reader turning the page. Even though the reader knows the story will probably have a good outcome for the protagonist, that element of doubt is what keeps them reading, because they have to know how the protagonist avoids the consequences.  4. Motivate your character. In a story, as in real life, the protagonist has a choice whether or not to get involved with the conflict. A hero isn’t a hero because they are brave. A hero is a hero because they choose to run towards trouble when other people are running away from it. This means that the protagonist has to have a reason to get involved and this is where their values and beliefs come in. On the other hand they can’t get involved because they are compelled to by some outside agency. In other words, it can’t be just about the job they do. There must be an opportunity to walk away early in the story and even later in the story when things get difficult. Take a typical private investigator story. The PI gets involved initially because they have been hired to do so, but they can also turn the case away if they wish. They don’t know at that stage that their life may be threatened. Later, however, they find that their life is on the line if they continue the investigation, so they can choose to walk away. Why they don’t walk away is because of their motivation, not because they are being paid. The motivation has to be believable, and it must fit in with the character you described in your pen picture.  5. Invest time in creating your villain Authors often spend a lot of time building good protagonists, only to let themselves down with their antagonist. Nobody is born bad, so there must be a reason for them becoming the person they are. It doesn’t matter the genre, your villain has to have his or her own back story which explains their behaviour. Just as with your protagonist, you may not use all the material you generate in developing your antagonist, but if you understand them it will add depth to your plot and your readers will understand them.  6. Create smaller conflicts to add complexity and drama. Sub plots are what turns a short story into a full length novel and those sub-plots are created with small conflicts that get in the way of your protagonist dealing with the big conflict. Imagine our PI, mentioned above, who owes money to a loan shark, who wants his money back. The PI spends time during the story dodging the loan shark, trying to raise the money to pay him back etc then, just as the PI is about to solve the case and confront the villain, they are snatched off the street by the loan shark and are threatened with dire consequences if the money isn’t forthcoming within the hour. There is several chapters worth of drama available in that short paragraph. Sub-plots are also a great way to put your minor characters centre stage for a while as they try to help the protagonist deal with the minor conflicts so the protagonist can get on with dealing with the major conflict. This is what injects "pace" into a story; the peaks and troughs in the action that keep the reader turning the page to find out what happens next. However, the sub-plots and the main plot must interact with each other. If the sub-plot has no impact on the outcome of the main conflict it is redundant, and the reader ends up saying “what was that all about?”, which is not a good thing.  7. Do your research This applies to any genre but is particularly important when it comes to specialist settings such as police, medical or legal dramas and historical fiction. Readers of that sort of fiction know their stuff and they expect their authors to know their stuff as well. I’ll give you a real life example. I recently read a book set during World War II. The first third of the book was set against the backdrop of an RAF Lancaster bomber squadron. It became quite clear that the author knew nothing about the RAF. He had researched the Lancaster bomber and knew quite a bit about that (but not as much as he should have known), but he was clueless about the RAF in general. As I’m a former member of the RAF he had me wanting to throw my Kindle at the wall in frustration at the gaffs he committed, and he completely undermined his credibility as an author writing about that period. Needless to say, the book ended up as DNF. What made it worse was that most of what he needed to know he could have found on the internet and the rest from one of the several standard works about the RAF during WW2. The golden rule is always “write what you know”. As that is a bit limiting the next best thing is to work out what you don’t know and learn about it. Learn everything about it. Like character development, you may not use everything you learn, but at least you won’t make the sorts of gaffs the above author made, your credibility will be retained and your story will be more authentic. It’s easy to say “Readers probably won’t know that, so I won’t bother researching it” – but some readers will know it and they are the ones who will write the bad reviews of your book.  8. Don’t show off. This includes using multi-syllable words when single syllable words will do and using technical, scientific or jargon words that readers won’t understand, or including unnecessary detail just to prove you’ve done your research. Your readers don’t want to have to read your book while holding a dictionary in one hand and an encyclopaedia in the other. So, use language that the average reader will understand, even if you know all the technical or scientific terms yourself. There will be times when you need to use those terms, in context, but make sure that you provide your readers with an explanation so that they will understand it too. You can have the protagonist or another character acting in place of the reader and have the “expert” explain what they mean in simple language, for that character’s (and the reader’s) benefit. This is often done in cop shows where the Forensic Medical Examiner has to explain post-mortem results in terms the lay person (the viewer) will understand.  9. Know the ending before you start. If you know how your story is going to end, you can construct a “road map” that will take your protagonist to their destination. One of the biggest problem for “pantsers”, as some authors are called, is that in not having a map to follow, they get side-tracked, which is confusing for the reader and it is hard for the author to get the plot back on track because they have confused themselves. It is OK to deviate from the map, but if you don’t have a map to start with you won’t know if you are deviating from it.  10. Write for your readers. Many authors are advised to “Write for yourself first” and that is OK if all you want to do is write. But if you want to write a best-seller, you have to write for your readers. You have to know what they want and what they expect, and you have to fulfil their wants and expectations. If you do that your book will get good reviews, which will mean it sells more copies. But if you don’t meet those wants and expectations, you can only expect bad reviews, which will stop sales in their tracks. What the readers want and expect will vary from genre to genre, so you have to understand your genre inside out, and that means reading books in that genre. Read the best-selling authors in that genre to learn from the best. Once you have established yourself as a best-selling author, you can then “write for yourself” in the certain knowledge that your name will sell the book. But you have to cross that bridge when you reach it, not when you are just starting your journey.  And Finally Nobody can guarantee that your book will be a best-seller. But if you follow the advice above, you will stand a better chance than those authors that don’t follow the advice. But if there is a key to success it is in the first three tips. Character, conflict and consequences. They are what make up the vital elements of the story. At least get those right and you are well on your way to writing a best-selling novel. Now that you have read this blog, why not take a look at our books to see if our authors have followed the advice that we have offered? Just click on the “Books” tab to see their work. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.

0 Comments

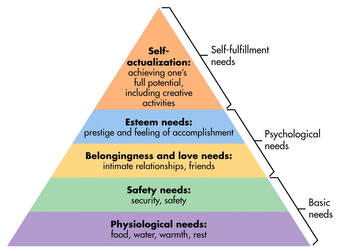

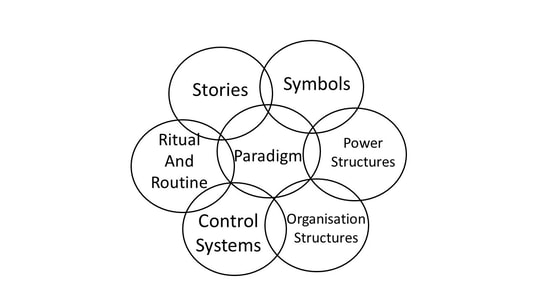

In last week’s blog we focused on some of the positives of being an Indie author, so it is only fair that we now look at some of the negatives. But we here at Selfishgenie are positive sorts of people, so we really want to turn the negatives into positives too. It isn’t always possible, but we have racked our brains and we think we have found a few ways of doing that. We’re not going to go all “turn that frown upside down” cliché on you. But we do want you to know that there is nothing about the negatives of being an Indie author that you should ever feel you can’t do something about. So, here we go with the negatives of being an Indie author.  1. You have to edit your own work. Some people love editing, some people hate it. But it is an essential part of being an author. If you want your book to be the best version of itself that it can be, you are going to have to do some editing, because the first draft of any novel is never going to be perfect. The first step to editing your draft is to put it out to beta readers. Many Indie authors think this is the final step because they want approval for their finished product. It must therefore be quite demoralising when their beta readers tell them that the book still needs work. So, go to the beta readers first, get their feedback, fix what needs fixing, then go back to a different set of beta readers for a fresh perspective. The feedback should be less damning and more complimentary, but you can still expect some suggestions for improvement. Rinse and repeat until the beta readers have no more suggestions for improvement, or until you think the suggestions are no more than nit-picking. There is no point in putting a book out there and hoping it is good enough. This process provides a degree of certainty. If all else fails, you can find editors on-line and pay them to edit your book. Be very sure of what you are paying for, however. Particularly make sure you understand the difference between editing the text and editing the narrative.  2. You have to do your own formatting. True, but if you set up a template so that from the first word of your book it is already formatted correctly, you will save yourself a lot of time. You may want two formats, a draft version that’s double spaced for later editing, and a final version, but word processing packages allow for speedy conversion from one to the other. We encourage authors to compose in the final format, because we edit using word processors too, which means double spacing isn’t required. We even publish a formatting guide so that potential authors can impress us by showing that they have researched us and know what we are looking for from them. There really is no witchcraft to formatting:

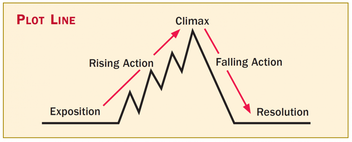

These aren’t hard and fast rules but take a look at the books you love the most and see how they are formatted. Copy them and you won’t go far wrong.  3. You have to upload your books onto self-publishing sites yourself. This can be time consuming the first time you have to do it, but after that you can upload an ebook and a paperback in less than an hour. Some sites are more difficult to work with than others, but if you do anything they don’t like they will tell you why, so you can correct it before publication. If you get the formatting right in the first place, the problems will be reduced. Covers are most tricky, especially for paperbacks, because they have to take into account the thickness of the book when it has been printed. Investing in a package such as Book Brush and learning how to use it is well worth the money and the time.  4. You have to market the book yourself. There can be no doubt that this is the hardest part of self-publishing, and it is also the part that Indie authors spend the least time and money on. Sorry, but if you think people are going to stumble across your book by accident, you are fooling yourself. If you think that “word of mouth” will sell your book, you are fooling yourself. If you think that plugging your book on social media will sell your book, you are fooling yourself. Yes, both word of mouth and social media have a part to play in book marketing, but it isn’t as big a part as some people make out. Book marketing requires knowledge of how to do it if it is going to work. Unless you want to spend money getting other people to do it, it is far better to spend money on learning to do it for yourself. Actually, you don’t have to spend money on learning. There are free on-line courses on marketing that will teach you the basics. But you have to invest the time and the effort if you want it to work. Investment in yourself is an investment that always pays back – so do it. But at some point you will have to pay for marketing services, especially advertising. We have posted several blogs on this subject and you can find them all in our archive. But the golden rule is caveat emptor – buyer beware. There are lots of “businesses” out there that promise a lot but deliver little. Look for recommendations from other authors and check their sales rankings - because they don't lie. That’s one of the best ways you can use social media when it comes to marketing.  5. Readers don’t take self-published authors seriously. Unfortunately, there is little we can do about that sort of prejudice. Also unfortunately, there are a lot of poorly written self-published books that would seem to confirm this bias (though not yours, obvs). There are a couple of things you can do to try to change the minds of readers when you encounter this bias. The first thing to do is to challenge this view. There are a limited number of agents and an even more limited number of publishers, so author supply outstrips publisher demand. Just because an author can’t find a publisher it doesn’t mean their book isn’t worthy. It just means there is no space for them at the table right now. The other thing you can do is to point out the growing list of bestselling self-published authors. We gave some names in last week’s blog, so you can scroll down and see them. Saying something like “How do you account for the success of L J Ross, who is self-published and has sold over 7 million books?” will leave the prejudiced person looking for a way out of the conversation. If they reply with “they got lucky” then start reeling off a few more names and asking if they all “got lucky”. Or maybe they sell so many books because they are real authors who tell stories that people want to read. I can’t promise that you will change a lot of minds, but it is only by challenging prejudices that we eventually eradicate them. If all else fails, offer them a free copy of your book so they judge you on merit instead of pre-judging you.  6. You feel so isolated and/or you feel like an imposter. Having a publisher comes with a support network that affirms your ability as a writer. And there is always someone available at the end of a telephone who understands what you are going through and is there with words or comfort. But just because you are self-published, it doesn’t mean you are alone. Join a writer’s group. Even if you live in an isolated community you can join virtually. Zoom has become a great boon when it comes to meeting other writers and discussing your problems with them – and being there for them to discuss their problems with you. Join on-line writers forums, for the same reason – but don’t try to use them to plug your books! I don’t recommend social media as your first port of call for support. While the vast majority of authors on it are supportive, it only needs one troll to start on you and it can ruin your day. Find the safe spaces and stick to them. But always remember – you are not alone. If the worst comes to the worst, you can always email us, even if you aren’t one of our authors. We support every Indie author, regardless. See our “contact” page for our email address. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  No Way Out! No Way Out! It is a common theme on social media, for authors to bemoan the fact that they have got their characters into a certain situation but can’t find a way out for them. I guess it is a sort of “writer’s block”, but it is one that is avoidable. Authors can be split into two broad types (at the risk of stereotyping); there are the “plotters” and there are the “pantsers”.  Plotters plan their book in advance, breaking it down to chapters, then scenes and even to paragraphs, depending on how focused they are on the fine detail. Some plotters spend far more time planning their books than they do actually writing them (OK, maybe an exaggeration, but they do spend a lot of time on planning). We are not here to talk about plotters. If you are one then move along, there is nothing for you to see here. (OK, stick around and read about how miserable things sometimes get for pansters if you want to). Pansters “fly by the seat of their pants”, hence the name. They sit down in front of their PC, laptop, tablet or phone (some even use a pencil and paper) and just start writing. They have no idea what is going to happen in their book until the words appear in front of them.  Life as a pantser! Life as a pantser! I am a pantser and proud of it. I think I’m more creative because of it. And yes, sometimes I get myself into a position where I don’t know what is going to happen next. But I have learnt from that, so it happens a lot more rarely than it used to. Which brings me to the subject of this week’s blog, which is how pantsers can save themselves a lot of anguish and a lot of time. I now have one simple rule that I live by when it comes to writing: never put your protagonist into a situation unless you know how you are going to get them out of it.  So, your protagonist gets into a fight and gets thrown down a well. Good bit of drama. No problem. But if you don’t know how they are going to get out, you could end up staring at that screen for a very long time. It could result in you going all the way back to before the fight started and re-writing the whole chapter so that this time they don’t get thrown down a well. Which means you lost a whole lot of time by not thinking about it first. So, here is a hypothetical scenario, as I would play it out in my head. Me. “I’m going to ramp up the action so that my protagonists is going to get into a fight.” Me in my head. “Good idea. How is it going to have a dramatic ending?” Me “He’s going to get thrown down a well, which is too deep for him to get out. And the antagonist then cuts the rope that’s attached to the bucket and throws it into the well with him, so he can’t climb up the rope.” Me in my head “Sounds good, but he’s eventually got to get out, so how will he escape?” Me, “Someone will come past, hear him calling for help and lower a rope down to him and haul him out.”  Now, you may think that’s good (or maybe you don’t). But is it believable? I mean, is it normal for people to just wander past carrying a bit of rope long enough to reach the bottom of a well? Yes, we expect our readers to suspend their disbelief, but we can’t expect them to believe in miracles (unless it’s a religious story, of course, where miracles are a routine explanation for everything). So, I now have to think about how this person is going to turn up out of the blue, carrying the rope. Me in my head “Where did this bloke come from and why is he carrying a rope?” Me (after a lot of head scratching) “He’s a bellringer in the local church and he has to replace the rope on one of the bells. He is just on his way to do that when he heard my protagonist calling for help.” Me in my head. “OK, that’s believable. Go for it.” It may be necessary to go back a few pages, or even a few chapters, to introduce the bell ringer, to add credibility to the plot. Maybe we’ll see him with his wife (it has to be a he so he is strong enough to haul a fully grown man out of a well), having breakfast and discussing what he is going to do that day, then we follow him on his walk to the church, which takes him past the well.  Guess which character is going to die! Guess which character is going to die! But that is easier to do than going back to square one because I haven’t given the matter any prior thought. If you are a pantser and all that sounds like a bit of a chore, then OK. It’s your story, write it your way. All I’m saying is that you can make life easier on yourself by not going hell-for-leather all the time. Just stop and think about what will happen next, especially when it comes to putting your protagonists in the way of danger. And if you think all the above doesn’t apply to you because you write romance, or another genre that doesn’t involve throwing characters down a well, think again! You will be putting your characters into unsuitable relationships from which you then have to extricate them. That is a metaphorical well. Some types of book make it easier to find additional characters at the right time than others. I’ll use a well known TV series to illustrate. In the original Star Trek series, we only saw a small number of crew members. But there was apparently a crew of 430. That made it easy to introduce a new face when it was needed. I’m sure we can all recall episodes where a previously unknown crew member joined a landing party, only to die almost as soon as they were transported to the planet’s surface. But that minor character was important, because his death (it was nearly always a man) alerted the rest of the landing party to danger and ratcheted up the drama levels.  Other settings allow this as well. Basically, any plot that is set in a large organisation: hospital, military, school, police, FBI, CIA et al provides scope to introduce minor characters when they are needed. When writing a book with a smaller, tighter setting, it is much harder to introduce a new character. For example, in Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe has to concoct a plot about cannibals coming to his island to kill and eat the character who would become Friday. When reading that as a child, I found it hard to believe. I mean, why would cannibals transport a prisoner across miles of dangerous ocean (Crusoe’s ship had already been sunk in a storm to leave him stranded) , when they could do what they wanted to much closer to where they captured him. Indeed, they could even do it at home. Credibility is important when introducing characters, especially if they have an important part to play in the plot, even if they’re only going to be in the book for a short segment..  Beware of remote locations Beware of remote locations So, that is something for you to think about if you are setting your story in a remote location, because drama means threat and threats have to be countered and the protagonist may not be able to counter the threat without help. In the film The Revenant (2015) the protagonist, Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio), teams up with a native American who saves his life when he becomes feverish, so this is a common trope and one that must be planned in advance. Even if it is only 30 seconds in advance. Finally, a word on the use of magic to solve your protagonist’s problems, for you pansters who write fantasy. I include miracles in that as well, even though writers of religious books wouldn’t consider them to be magical. However, the same problem exists.  If the only way out of their predicament for your protagonist is to use magic, then it’s bad idea. If magic is always going to be the solution, there is no point in reading the book. There is no drama for the reader if they know that no matter what happens, the protagonist is always going to be saved by magic. Magic has its place in fantasy, but only when magic is being used against it. Even then it should come at a cost to whoever is using it, so that further use is discouraged. Even Shakespeare, who occasionally used a bit of magic, knew to use it sparingly. OK pansters, lesson over. And all you plotters can now stop gloating and get back to your flow charts. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  It is the dream of all Indie authors: to snag an agent or a publisher and get that elusive publishing deal. Yet so few Indie authors are able to fulfil that dream. But it is achievable, and it is probably easier than you think. However, it is also somewhat counterintuitive to do what is necessary to fulfil the dream. It may also require the author to make a few compromises. OK, if it’s that easy, tell us the secret, oh Selfishgenie. OK, we will.  The first thing you have to do is recognise that publishers hate taking risks with new authors. Risk threatens to reduce profits and there are stories in the industry of publishers being left with warehouses full of books because they took a gamble on a new author that didn’t pay off. These stories are probably apocryphal, but they are enough to give publishers nightmares. In that case how do new authors ever get signed? The answer to that is that it isn’t always the author themselves that represents the risk. It’s the type of book they are writing. The author may be the next Ernest Hemingway or Hilary Mantel in terms of the quality of their writing, but if they aren’t writing the sort of books that readers want to read, then they will never become bestselling authors. It is quite possible that in today’s market, Hemingway would also be unable to find a publisher because his type of books aren’t selling these days (my speculation, of course) Which is why new those authors represent a risk. This is where things become counterintuitive.  You may think that to get that elusive publishing deal your book has to be different from what is already out there in the bookstores. You would be wrong. It's the exact opposite. Your book has to be the same (or at least similar) to what is already out there. To de-risk their industry, publishers follow the reading fashions. If J R R Martin’s books are selling, then publishers are hungry for books just like his. If Lee Childs’ books are selling, then publishers will also be hungry for books like his. So, if you want to snag that elusive publishing deal, your books have to follow the fashion. By publishing books that are what the public is reading at that moment, publishers are able to de-risk their products Give the public what they want and they’ll come flocking to your door.  We already see this in cinema, of course. In the last decade, 5 of the top 10 box office hits were superhero movies, four of which were from the Avengers franchise and the 5th was Black Panther. Of the remaining 5 one was from the Star Wars franchise, another was from the Jurassic Park franchise and two more were Disney films, which are always popular. If that’s what the public wants, is it any surprise that we get so many superhero films, Star Wars films, Disney films et al? And the same applies to books. This desire to follow the fashion then feeds back to agents. If publishers want a particular type of book, then agents will want to find authors who are writing that type of book. Because it is easier, and more lucrative, to sign authors who are writing the sorts of books that publishers are looking for. So, sending an agent something different is not going to get you signed. Of course, going to Bloomsbury or Scholastic Press and offering them a Harry Potter clone isn’t going to help the Indie author. After all, those two publishers already have the original Harry Potter. No, you need to approach a publisher/agent that hasn’t got Harry Potter and offer them your clone.  At the same time as responding to fashion, publishers also create reading fashions. After all, if all the publishers are producing Harry Potter clones, then that limits the choice for readers, so they buy them even if they would actually welcome a change. We see this each year with clothing fashions. If manufacturers decide that green baseball caps are going to be “in” this year that is what they will produce, and they will pay “influencers” to get the public to wear them. Pretty soon all you will see will be green baseball caps! Then, next year, because everyone already has a green baseball cap, they’ll switch the colour and repeat the trick so they can sell more product. And we fall for it, so we only have ourselves to blame. Exactly the same methods apply with books. But you don’t want to write Harry Potter clones or Jack Reacher clones, do you?  You have your own story ideas and those are the ones you want to work on. You have “artistic integrity” and you won’t be dictated to with regard to your plots, your characters or your writing style. OK, I respect that. But artistic integrity doesn’t put food on the table. When you are a big name writer you have a bit of power that you can exert. Your name alone will sell books. That means your publisher is likely to be more flexible about what they will buy from you. And if they aren’t flexible, your name is big enough to open doors to other publishers who might allow you to write what you want, because you no longer represent a risk. You are “box office”, as they say in the movie making world.  It’s the reason why celebrities who can barely write their own names are able to get publishing deals. It’s not the quality of the book that sells it, it’s the name on the cover,. But you have to be a “name” first and that may mean compromise. Write what the publishers want now, so you are granted the freedom to write what you want to write in the future. So, what should you be writing right now in order to snag that contract? The answer to that is likely to change from month to month and year to year, which isn’t helpful. The best sellers list on Amazon will tell you what is fashionable right now as will the Sunday Times (or New York Times in the USA) best sellers list, but that won’t tell you what will be fashionable in 6 months’ time when your book is ready for querying. Fortunately, fashions in reading change quite slowly, certainly slower than they do in clothing, so you probably have time to get on the bandwagon with your next book. The top three genres (UK) to write in are Crime and Thrillers (33% of the market) , Fantasy Fiction (22%) and Action & Adventure (20%). There are, however, subdivisions below those headline genres and not all of them are as popular as others. But what you will probably notice is that the most popular books right now are character led, not plot led. Less popular at the moment are Modern Classics (No idea, but they are only 11% of the market), Horror (11%) and Short Stories (14%)* Some genres are so unpopular that their market share doesn’t even register on the graphs.  Some publishers do allow themselves to take a few risks. They look for good new writers and offer them publishing deals. However, they won’t throw a lot of money into marketing their book. At least, not the first one. The first print run of the hardback version of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was only 500 books, most of which went to libraries. That’s how much faith Bloomsbury had in J K Rowling for her first book. Fortunately it was the American market that saw its potential and made her the best-seller she is, while the UK market caught up later. So, yes, you might find an agent and a publisher willing to take a risk on you even if you aren’t writing whatever is fashionable. But it is probably going to be a harder furrow to plough. * Figures for 2020, the most recent we could find from a reliable source. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  In last week’s blog I discussed what made up a culture, because it is so important when it comes to anchoring both your fictional world and also your fictional characters. In several places I used the word “power” as something that was needed to exert control. Who holds power and how they use it is an important part of culture as it shapes the way people behave, which is why culture is important in a novel. Understanding power is also very important in developing characters and plot, as I hope to demonstrate. Give the right characters the right levels of power in the right form and at the right time, you can do anything in a plot. A lot of that power isn’t actually held by the protagonist or antagonist, it is held by other characters, which makes for a more complex, and therefore more satisfying, plot.  Is your protagonist powerless? Is your protagonist powerless? However, this makes it sound as though there is only one sort of power. It is clearly visible in an antagonist, who arrays all sorts of powerful forces in order to frustrate the protagonist. However, this would suggest that the protagonist has no power of their own. If that were true, then the protagonist could never come out on top in a novel. In order to overcome power, the protagonist must have at least the same level of power. Either that, or they must be able to strip the antagonist of their power, in order to provide an equal “match up”. This can be seen in Lord of the Rings, where Frodo’s allies keep the Dark Lord diverted, concentrating on battles further away, while Frodo and Sam sneak into Mordor by the back door. They use alliances to create a large enough power base to take on Sauron. Stripping power away from the antagonist by a weaker force is demonstrated in two films. The first is Star Wars, where a single X Wing fighter destroys the Death Star. The same trope is used in Independence Day when Will Smith and Jeff Goldblum plant a nuclear device inside the aliens’ mothership, robbing them of their defences.  What sort of power did David use to slay Goliath? What sort of power did David use to slay Goliath? Both these acts render the antagonist(s) powerless, allowing the protagonists to triumph. Both of those are really David and Goliath stories told a different way. But when he accepted the challenge of Goliath, David knew something that Goliath didn’t. He knew he possessed “expert power” (see below). And if you think that power games are only the tools of action adventure novelists, then think again. It requires power of some sort to thwart the lovers in a romance. It just isn’t the sort of power that comes from the barrel of a gun (well, not usually). So, what sort of power can the author use to win the conflicts into which we send our protagonists? Studies of power structures have been carried out in business so that they can be understood. But don’t assume that they only apply to business. Businesses are made up of people and power is only of use if it can be used to control or influence people. Politics works pretty much the same way and if you belong to any sort of organisational structure, right down to the village darts team, you will encounter some sort power being used to some degree.  The fact that you don’t always see that power being wielded is a mark of how subtle its use can sometimes be. You don’t always have to plant a nuclear device in an alien spaceship in order to wield power. What types of power are there? Amarjit Singh PEng F.ASCE published a paper in 2009 which analysed this question, drawing on the findings of several other researchers. He studied several sources of power.  First we have legitimate power, aka positional power. This is power that “comes with the territory”. A Prime Minister or President will wield that sort of power, as will the CEO of a company. This is the sort of power that we are familiar with, because even the Evil Emperor will regard their power as being legitimate. After all, there is no one (they think) that can deny them their power. Crime bosses exercise what they regard as legitimate power, backing it up with violence and the use of weapons when needed. Just like Presidents or Prime Ministers who take their countries to war. The circumstances may be morally different, but the same sort of power is applied to make it happen. The police hold legitimate power, because they are established under laws passed by the government. However, they can also abuse the power invested in them. Within any organisation there are people who hold power. The amount of power may vary depending on their pay grade, but they all have it to some degree. Even the guy or gal on the production line has the power to bring it to halt if they walk off the job. So that one was easily dealt with.  Being able to bestow rewards is a source of power. Being able to bestow rewards is a source of power. Next we have “reward power”. Even a quite junior manager can exercise reward power, deciding who will receive bonuses, who will get a promotion and who won’t, right down to who gets the easy work and who gets to clean out the sewer. That sort of power makes sure people do what the manager wants them to do. A lot of this power is delegated from above, but it is something that can be used or abused. But ordinary members of the public also use reward power. We tip waiters and cab drivers for good service – and they know that if they do a good job they’ll get their tip. (I know this is different in the USA where everyone gets a tip regardless of whether they provided good service, but I’m not in the USA). That means the customer holds the power to control their behaviour. We may offer a Maitre D a small bribe to find us a better table (or any table at all). We also use reward power when we decide to go back to the same restaurant because they provided good service or avoid a restaurant that gave bad service. We call this “consumer power” and we all have it to a certain degree. All we have to do is adapt the concept for our novels. The prospect of a reward can get people to do what we want in a story. Treasure Island is based on the idea that if the crew of the Hispaniola cross the world with Squire Trelawney, there will be a reward at the end of it, when the treasure is found. That is a clear use of reward power in a novel.  Coercive power is fairly self-explanatory. It is based on fear. “Do what I tell you, or it won’t go well for you”. This isn’t seen in the workplace as often as it used to be, employment tribunals have seen to that (in the UK anyway), but it is still found outside the workplace. The coercion doesn’t just have to involve the threat of violence. Blackmail is a form of coercion, as are threats of isolation from the group – what we call “Being sent to Coventry”. There are probably other forms of coercion you can think of. Moral blackmail - convincing people "it's the right thing to do" - is also a form of coercion. What some people think of as persuasion or influencing can also be interpreted as coercion if it is taken beyond certain ill-defined limits. And, of course, coercion is often seen in bad relationships.  In the land of the blind, the one eyed man (or woman) is King. This alludes to expert power. If you know something, or understand something, that nobody else knows or understands, it is a source of power. This is often seen in wage negotiations. Back in the 1970s and 80s IT experts could pretty much write their own salary cheques, because so few businesses knew how to use computers. Today, however, that knowledge is commonplace and IT wage levels aren’t as generous as they once were. So expert power isn't always permanent. In fiction, we often make our protagonists experts in some field or another. Robert Langdon, the protagonist in the Da Vinci Code, is an expert in symbology. Tom Clancy’s protagonist Jack Ryan started out as an expert in interpreting military intelligence. Both are ordinary people at heart but become powerful through their application knowledge. In Lee Child's "Jack Reacher" novels, Jack is an expert in many fields. Even if we don’t make the protagonist an expert like Robert Langdon, we will give them special skills that they can use, such as being experts at unarmed combat. That is a source of power when they get into a fight and allows them to win. As mentioned much earlier in this blog, David had expert power which he used to defeat Goliath. He was an expert in the use of a slingshot, which negated Goliath’s size and strength. In cosy crime novels, amateur detectives outshine their professional counterparts by applying their expertise to solve crimes. Because they aren’t hide-bound by procedure, they can let their expert knowledge take them in directions the professional couldn’t or wouldn’t consider (at least, as far as fiction is concerned they wouldn’t consider). But in the end the amateur still requires the legitimate power of the police to make the actual arrest. So, you have two sources of power working within one book. If the murderer is also an expert in poisons, that is another source of expert power – which gives them the power to commit murder.  Charisma is a source of power. Its proper name is “referent power”. We often hear of charismatic leaders. We might also say that people admire or worship them. We see this a lot with celebrities, who use their referent power to become rich. Its basis is entirely due to how one person views another. If you don’t regard a person as charismatic (like a few politicians I could name), you won’t fall under their influence. People are drawn to charismatic people and are happy to help them. Charismatic people are therefore able to use that as a source of power, using their admirers to do their bidding. The only difference between the charismatic protagonist and the charismatic antagonist is what they ask their admirers to do. Robin Hood is probably the best known charismatic protagonist (if you are religious, it may be Jesus or Mohammed). In romance a common trope is the charismatic person who holds one of the star-crossed lovers in thrall. One way that charismatic power can be thwarted is to expose a character defect that hasn’t previously been visible, such as a cruel streak. It breaks the spell and sends the lover back to the one he/she should really be with.  You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours, is otherwise called “reciprocal power”. It can also be called “resource power” as it usually involves a trading of resources. It requires both characters to have something that the other character needs. How valuable the resources are will influence the balance of power. In this case valuable doesn’t refer to intrinsic value, it refers to how much the character needs the resource. If you have the gun I need in order to go after the antagonist, I might be quite generous in what I offer in exchange. But the resource doesn't have to be physical. Politicians, for example, trade favours in order to gain support and to form alliances. In LOTR each of the fellowship has something that Frodo needs to help him get to Mordor. The most obvious is the magic wielded by Gandalf, but Frodo would have been helpless in the caverns of Moria without Gimli's knowledge. Aragorn is the King behind whom men rally. Even Sam Gamgee has something that Frodo needs – his bravery, steadfastness and determination. Without Sam, Frodo would never have made it into Mordor. And, in exchange for the resources that each of the fellowship provides, Frodo does the dirty work for them and carries the ring. There is even a conference at Rivendell where the negotiations are held, though it isn’t depicted as a negotiation.  What sort of power do you have? What sort of power do you have? So, as you can see, power isn’t something that is one sided. In addition, the sum of the power that the protagonist can bring to bear must be at least equal, if not greater, than the power of the antagonist. Either that, or you have to find a way of stripping the antagonist of their power. James Bond has to kill a lot of henchmen before he can go mano y mano with the villain, which is no different than getting a nuclear device onto an alien mothership. As an exercise, you might want to analyse the sort of power you are able to wield in different circumstances. For example, how much legitimate power do you have? How much resource power? How much reward power and how much referent power? If you are the only person in your place of work who knows how to use the photocopier, you have "expert power" - at least until someone else reads the user manual. Although we might not always feel it, we are all able to use power at some time in our lives, even if it is only every few years at the ballot box. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  There was a question on Twitter recently that asked what authors thought was the most important thing to think about when world building. The Tweeter listed a few considerations, amongst which was the word “culture”. I Tweeted a reply to point out that culture wasn’t a single thing. It was a number of related things. That exchange of Tweets led to this blog. Loosely termed, culture could be described as “the way things are done around here”. But that does oversimplify things a lot.  To think of culture as a single thing is like thinking of car just in terms of its exterior shape. It may look nice, but without an engine, gearbox, wheels, etc the car is nothing more than a pretty shape that serves no purpose. A working car is a “system” - and so is a culture. My training in cultural issues came while I was working for a living in business and at that time many businesses were struggling to change their cultures from old fashioned, top down, target driven, tightly controlled workplaces to places where the employees had greater input which, in turn, resulted in greater job satisfaction and hence to greater productivity. Such cultural change is not easy to bring about. Managers in those businesses often thought that such a change robbed them of their power and status, so they opposed it. They couldn’t do so openly, but they became experts at undermining change without revealing themselves. So, who would secretly oppose change in your fantasy world – and why?  Trades unions also opposed such change, but more openly, because they wanted a workplace that involved conflict as conflict formed their raison d’etre. A happy workplace is one where conflict is rare, so the unions have little part to play, so they don’t wield any power. Finally, the employees themselves feared change, because it brought uncertainty. This was especially true in businesses with a previously bad reputation for employee relations, because there was little or no trust in authority figures. A colleague of mine, with a PhD in organisational change, pointed out that “if you can’t change the people, you have to change the people”. In other words, there may be a few casualties along the way as the people who resist change are quietly shown the door to make room for people with more open minds. But that was business. What has that to do with “world building”?  It isn’t just fantasy authors who have to consider culture. All characters in all novels exist within a culture. Some of these are easy for us to relate to, because they are familiar, while others may not be. But if you get the culture right for your story, it will make your character’s conflicts easier to understand. This is especially so if they are taken out of their own, comfortable culture and placed in one where they feel like an alien. Just going to a different town can make some people feel like that, so imagine what it feels like for someone going to a country on the far side of the world - or the far side of the galaxy. Understanding the elements that make up a culture allows the world builder to build something that is believable. The granddaddy of fantasy, Tolkien, got this right (mainly) with his Lord of the Rings trilogy and authors who have modelled themselves on Tolkien’s style tend to get the culture of their worlds right as well.  Experts on culture talk about the “cultural web”. These are the interconnected elements that make up the organisation’s culture. If you are worried about my use of the word “organisation” please don’t be. I’m not using it in the business sense. Any society is also an organisation and the world you build is just another society, supported by its own cultural web. The stronger it’s cultural web, the stronger the society that comes out of it. One of the reasons that revolutions fail is that they sweep away an old, outdated culture, but neglect to put the right elements into place to support the culture they want for the future. This leaves a vacuum into which counter revolutionaries can slip to undermine the new regime. Your fantasy world is just another form of country, with its pro and anti-revolutionary elements. If your hero wants to bring down an evil empire, they need something with which to replace it, or the old regime will simply return in a new disguise – just as Sauron was able to return in LOTR. Think about Putin and Russia in 2023, compared to the old USSR which everyone thought had been swept away in 1991. The similarities are many even though it isn’t now a communist state. But it isn’t a democracy either. The leadership and political ideology may have changed, but the underlying culture didn’t. So, what makes up the cultural web? Well, the graphic below lays it out in visual form, but I’ll take you through the various elements.  At the centre is the “paradigm”. This is the set of ideas or concepts that make up the world that you are building. Some of these are mutually exclusive. You can’t have a world ruled by a King that is also a Republic, for example. This is where your antagonist becomes very important. Whoever is running the Evil Empire has to have some reason for doing it. They must also have some idea about what they want achieve from what they are doing. This is where LOTR actually fails, for me. I can’t understand what satisfaction Sauron gest from all that power. Just desiring power is too shallow for me. Power needs a purpose, otherwise it is of no use. So, to start your world building you have to construct a paradigm for it. That is all about the ideas and beliefs that underpin whatever its happening. What does “Evil” want to achieve and what does “Good” want to put in the place of Evil. Those things will define how the people live. If it is a tyranny, then you can’t give the people any power when it comes to decision making. On the other hand, if it is a collective, then the people will have plenty of say in what happens. Those are two extremes, of course.  Surrounding the paradigm are the six inter-connected elements that make the paradigm work. Leave out one, or put the wrong things into it, and the paradigm itself won’t stand up to scrutiny. For example, if you have a tyrant that controls the lives of everyone, you can’t also have an independent legal system, because that would be able to say “no, you can’t do that” to the tyrant. Sauron didn’t have a Court of Appeal, for example. Instead he had Ring Wraiths and Nazgul. So, the most important bit of the cultural web, after the paradigm, is the organisational structure that supports it. Traditionally there are three parts: The lawmakers (tyrants, kings, nobility, politicians, etc). Then there are the people responsible for applying the law (Civil servants, administrators, local government, police, Ring Wraiths etc) and finally there is the legal system that sorts out the disputes over what the laws really mean and how fairly they are applied. Even if you have a tyrant running your world, you’ll still have a legal system – it just won’t be a very fair one. For example, the legal system may just be made up of “enforcers” who go around imprisoning, or even executing, anyone who criticises the ruler.  Next up are the power structures. Now, you may think that I’ve already covered those above, but not everyone who wields power is part of the organisational structure. Other people hold power of one sort or another. Businesses, trades unions, religions and more. Who you give power to in your world is quite important as those people can be enemies or allies, whichever you choose them to be. And the amount of power they wield can have a serious impact on your plot. An ally who is powerless isn’t of much use to you and an enemy without a source of power is easy to beat. Your magical figures will fit under this heading, because magic is a source of considerable power. Control systems are a bit abstract in many ways. If you are a King and you make a law, how do you make sure that the people obey that law? There has to be some way to do that. The most obvious example is the police and legal system, but there are other ways of exercising control. Fear is one (don’t stand on a balcony in Russia), wealth is another – either as a reward or a penalty. Control of other resources is a source of power, so it's another way of ensuring compliance.  So, how does your tyrant make sure the people obey? And if you want to depose the tyrant, what control systems must you dismantle or subvert? The whole point about the One Ring was that it was able to control the beings that wore all the other rings. It was even engraved on the inside of it, so everyone knew what it was! And if you dismantle the existing control system, by destroying the One Ring for example, how do you then exercise control afterwards? Or do you let your world descend into anarchy?  Rituals and routines form an important part in maintaining control over people. Getting people into church (or a mosque or a temple) every week, for example, prevents adherents to the religion from drifting away. The more people you have in your religion, the more power you wield, so you don’t want to lose any. It is also where messages can be sent out and heard. Historically, the pulpit has always been used by governments to send out its messages and to exercise control. I’m sure we can all think of countries where this still happens. But those aren’t the only rituals. Weddings, funerals, christenings, workplace meetings, even getting together once a week for a family meal, to watch TV or go to a football match, all form part of the rituals that identify us as being part of a community. Taking part in a ritual says “I belong here.” They also say “I am conforming, so you don’t have to send me to prison or execute me.” They can be used for good as well as evil.  Believe it or not, stories play a very important part in culture. Stories about heroes encourage the sort of behaviour you want to support, while stories about villains tell you what sort of behaviour you want to discourage. It’s why Bible stories are told, it’s why Aesop wrote his fables and it’s the way the media influences public onion on a wide range of issues. (and you thought they just reported the news) But the heroes and villains of these stories will be different in every culture. In a communist country the heroes might be Marx and Lenin. In Britain Robin Hood is a hero, which is no mean achievement for a thief. Marvel and DC comic books are all about telling stories that express American values. Cults create heroes out of ordinary people, often stretching the truth or telling lies to make the person seem more significant than they were. The media often creates heroes – and villains. Sometimes they even start as heroes and then get turned into villains when the media wants to change the narrative. You will be familiar with the old saying that one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter (Nelson Mandela). And one man’s despot is another man’s saviour of the nation – politics tells us that because we all see politicians as one or the other depending on which side of the fence we are viewing from. It’s the stories that are told about them that make them one or the other.  Finally, we have the symbols of our culture. Many of these are physical, such as flags, buildings, coats of arms, etc. We have symbols of wealth that encourage people to strive to achieve. Religions are very big on symbols, as they are with rituals. We salute the symbols we support and we tear down those we despise. But there are also more abstract symbols with which we engage. Symbols may take the form of songs (national anthems are a symbol), the sports we play or watch, etc. The language we use is a symbol, as are phrases such as “motherhood and apple pie” because they are symbolic of cultural values. If you wear any sort of badge (including wrist bands etc) or you wear a tee-shirt with a slogan on it, you are wearing a symbol that declares your allegiance or an ideal you support. The same will apply to your characters. I'm sure that we can all think of symbols that have played a powerful part in events. A swastika will forever be a symbol of hate. So, a lot to think about if you are a world builder who wants to create a world that is believable. I have used mainly real world examples to illustrate what I mean, so if you are a fantasy author you will have to imagine the equivalents for your world. But with a strong culture that your readers can identify, the hero will be able to do things to change the culture for the better and the villains will oppose those changes, which makes for a more satisfying plot. Your hero may spend a lot of time killing dragons, but what do they do with the dragon’s horde once the dragoon is dead? If they keep it for themselves, they are just as bad as the dragon (Thorin Oakenshield in The Hobbit), so they must use it to either support or change the paradigm you created for their world. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  In last week’s blog we asserted that understanding a protagonist’s motivation was one of the critical factors in creating interesting characters for stories. In fact, we went further than that and said authors should be doing the same for antagonists as well. But in order to do that we also need to understand how and why motivation works in general otherwise we can’t attribute the right motivators for the correct reasons. For example, if our story involves a love triangle, what might motivate one of the characters to abandon their love in order to make the object of their love happy? In a selfish world like ours that makes no sense. But it is a well-used trope in romance. Which is what this week’s blog is about. It’s a whistle stop tour of motivational theory and what it can do for you as an author.  Motivation or Incentive? Motivation or Incentive? The first thing to understand is that there is a significant difference between motivation and incentive. The big difference between the two is that an incentive can never be enough for a person to place themselves in jeopardy. After all, there’s no point in being paid £1 million (an incentive) if you are going to end up dead and can’t spend it. But a person may take a dangerous, high paying job if it is the only way to provide security for the ones they love. Love is a motivation, money is an incentive. To put it another way, motivation drives us, but incentives can only pull us. In fiction we are always looking for what drives the character. The lure of wealth may be an incentive for a criminal, but it carries the risk of imprisonment. So, what motivates criminals to take that risk? Understanding that motivation makes the criminal far more interesting than just the lure of wealth, which is quite shallow.  Psychologist Abraham Maslow, the granddaddy of content based motivational theory. Psychologist Abraham Maslow, the granddaddy of content based motivational theory. Theories of motivation are generally grouped under one of two headings: content and process. Content theories focus on what things provide motivation and process theories focus on how motivation occurs. To add depth to a character it isn’t enough to know what motivates them (content) it is also important to know why (process). The two together provide layers of complexity and that makes characters more interesting. Abraham Maslow is the granddaddy of content theory. He theorised that in order to function at a higher level, you first required certain needs to be satisfied. In other words, you can’t create great art if you are starving to death. So, you have to have your hunger satisfied before you can achieve your goal to become an artist. This became known as a “hierarchy of needs”.  Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Maslow's hierarchy of needs. You may, at this point, be tempted to mention the name of Vincent Van Gogh, who only sold one of his paintings during his lifetime. But he wasn’t actually poor. He had a very well paid job selling art in his brother’s Paris gallery before he left to pursue his own artistic career. Van Gogh wasn’t penniless at the start of his career – though he may have been by the end. In practice this means that we are first motivated by a need to survive, but if that is secure we can then move on to be motivated by something at a higher level. In fiction this means that if a character is trapped inside a burning building, they aren’t going to be interested in catching the person that lit the match. Only after they have escaped the inferno will they turn their attention to that. A vagrant living on the street wouldn’t be motivated enough to help a damsel in distress, because their priority would be their own survival. But they can be incentivised to help the damsel because the incentive (usually money) secures their basic needs. However, if it looks like they may die in the attempt, the incentive would no longer be enough. They would need some other motive, such as love for the damsel. While good Samaritans may exist, they don’t place themselves in danger. They need motivation for that to happen.  GET MOTIVATED! GET MOTIVATED! As can be seen from that example, content based motivation is a tricky business and if you don’t understand those sorts of basics, your readers won’t believe in your characters. But notice the sorts of things that appear in Maslow's hierarchy of needs diagram from the third level upwards. there's plenty of stuff hidden behind those short statements with which you can play in order to provide your characters with motivation. But what content theory also makes clear is that what motivates us isn’t constant. Our motivation can change in response to circumstances. For example, we may be highly motivated to succeed in our careers, working long hours and totally immersing ourselves in our jobs. Then one day we meet the girl (or boy) of our dreams and suddenly our career isn’t the most important thing in our lives anymore. Winning the heart of the object of our desire is now what is uppermost in our minds, to the extent that we may throw away our career in order to be with that person. That, of course, runs contrary to Maslow’s theory, because if we lose our job we also lose our security. So, it appears that some motivators are more powerful than others, at least for some of the time.  Achievement and competition. Achievement and competition. Achievement and competition are theories of content motivation studied by David Mclelland. Today this is often portrayed in fiction as a negative thing; highly motivated achievers or competitors are often depicted as criminals or cheats, driven by their desire to win at all costs. Which is odd, because the sports stars we admire the most are highly motivated by competition and achievement. Not only do they compete in their sporting arena, they also compete off the field by consistently trying to beat their own best performances, in the gym for example. Name the sports star you admire the most and you are naming a highly motivated competitor, but modern fiction suggests you will also be naming a cheat. I think we need to change that stereotype with positive competitive role models in fiction. Is competition and high achievement a bad thing? That is for you to decide, but I know of one author who uses competition as a motivator for the success of his heroic characters.  Psychologist B F Skinner Psychologist B F Skinner When it comes to process theories, there is one that is usable in fiction. It is “reinforcement” theory, developed by B F Skinner. This is based on positive outcomes of certain types of behaviour. In fact this can be traced back even further, to Pavlov and his dogs, but Skinner is better known for his study of humans. If you can imagine a misbehaving child being given a biscuit in exchange for better behaviour, it will soon learn that if it misbehaves biscuits will be forthcoming, so that the reward becomes the motivator for bad behaviour. Extending that theory into adulthood, if a character believes that rewards come from bad behaviour they will continue to behave badly – which is great motivation for criminal characters. The opposite applies as well, of course. If good behaviour results in good outcomes, then a character is motivated towards good behaviour. It may also surprise them when their good behaviour results in a bad outcome, eg their loyalty being betrayed. That could be enough for a previously good person to start behaving badly. Because when we add emotions to motivation, we start to get a powerful mix. I have already mentioned the power of love to derail a career, but there are plenty of other emotions that can affect motivation. The most challenging question it is ever possible for an author to ask is what makes one man brave and another a coward. This is especially so in stories that involve death but can also be played out in terms of moral behaviour. Nature has given us three responses to danger: fight, flight or freeze. What makes one person choose to fight, another choose to flee and another to do neither (freeze)? Fear is a natural response to danger, so all three responses should be regarded as equal, because nature gave us the choice. But our regard for bravery and our contempt for cowardice shows that we don’t regard all three responses as being equal. Very often the individuals who take the actions can’t answer our question. Ask most decorated war heroes why they did what they did, and they are unable to answer, or they fall back on clichés like “duty”.  But duty only takes us so far. A soldier standing firm in the line of battle is doing his duty. A soldier that charges an enemy position in order to save a comrade is going far beyond that. It happens in real life, but quite rarely which is why medals such as the Victoria Cross and the Congressional Medal of Honour exist to recognise such actions. But in fiction it is the norm for the protagonist to exhibit that level of bravery and persistence. So, what can we give them, in emotional terms, so that they do that? And, more importantly, how can we create a backstory that shows how they developed that quality, based on what we know about motivation? This is where Skinner’s theory becomes important. If during their developmental years the character is rewarded for having beliefs and values that we admire, but isn’t rewarded for having beliefs that we detest, the qualities for which they were rewarded will become the motivators. They will also become the barriers when those qualities are undermined. The flawed protagonist is one whose beliefs and values are called into doubt by events, which cause them to question their beliefs and results in internal conflicts. The loner cop who drinks way too much whisky didn't start out that way. Something made them like that and the author gets to decide what it was. There is far more to motivation than I have had time to cover in this blog. I recommend further research. How much you include in a story is up to you, but layered characters with strong motivations are always going to be of more interest to readers than shallow characters who only respond to incentives. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.  As publishers, we get sent a lot of books. But that’s OK because we’d be in trouble if people didn’t send us their books. It would be nice if I could say that all those books are great, and we can’t wait to be able to get them uploaded and out there with the reading public. Unfortunately, we can’t say that. I would estimate that perhaps 50% of what we are sent is never going to get published; not by us and not by any other reputable publisher, large or small. It usually takes us less than an hour of reading to make that decision. About half the rest start off well but then start to run out of steam, usually around the 30 to 40,000 word point. It was probably around that point that the author realised that writing a book wasn’t quite as easy as they had thought, but they kept ploughing on anyway, in the hope that something great would come out of it. Sadly, it didn’t, but it will take us maybe 2 – 3 hours to decide to pass on those books.  Finally, we get to the 20% to 30% of books that stand a real chance of finding readers. Those are the ones where we invite the author to work with us to try to get the book into its best possible version before we finally publish it. Some authors then pass, because they think their book is good enough already and doesn’t require our interference, or maybe they think they can get a better deal elsewhere (and maybe they can). But if a book is on our website it’s because the author has been more realistic and understands that all work can be improved, even if it is only a little bit. Just once in a while we get a book sent to us that we know from page 1 is going to be good. How do we know that? Because we get so absorbed in it that someone has to tap us on the shoulder and remind us that it’s time to pack up work for the day. Even then we’ll upload it onto a tablet so we can keep on reading it on the way home (but not if we’re driving). "Character = Conflict = Plot" Those books may be rare, but when we analyse what they have that other books don’t have, it usually comes down to just 3 things.