|

Disclaimer: We are not connected to Book Brush in any way other than as users of the product that has been reviewed. This review has not been paid for by Book Brush or by any other person or organisation.  This article is a review of the Book Brush app which allows authors to design their own book covers, rather than having to pay someone else a lot of money to do that for them. I have to say up front that some of the things that Book Brush allows you to do can be done just as easily in PowerPoint (if you are good at using PowerPoint) but, equally, some of the features are unique. And what is most unique as that it draws together everything you may need to be able to do under one URL. The service is provided on an annual subscription basis, charging at 3 levels: silver, gold and platinum. We paid for the silver level ($99, about £85) as that provided the things we needed right there and then (we knew we could upgrade later if we wanted to). Looking at the other two packages, it is hard to see them offering that much more – but on the other hand if it is something you want to do repetitively and you have no other way of doing it, you may regard the extra money as being well spent. I’ll cover the differences in the subscription levels a little later in this blog. "doing it myself was a no-brainer" The first thing I found useful was the introduction video that showed me how to use the app. I was able to watch it before I had even subscribed, and it persuaded me that what was on offer was going to save me money. Typically, we pay a designer on fiverr.com around $100 to provide us with an ebook and paperback cover package (with us providing the images to be used) and, as publishers, we may need a dozen of those each year, costing around $1,200. So, paying $99 a year and getting one of our team to do it was a no-brainer, providing we can create the sorts of designs that we want. How long does it take to design a cover?  Having watched the video and learnt the basics, and combining it with some use of PowerPoint (I’ll tell you why later) I was able to create a cover for the next Carter’s Commandos book in around 15 minutes. OK, the design isn’t complicated, but using the sorts of templates that are available within Book Brush, it wouldn’t have taken much longer to produce something more elaborate. I was able to do that after watching just one video and spending about an hour playing around with the various features. What’s more, I rather enjoyed doing it because the results are so easy and quick to see and it’s fun to be able to experiment with different designs. Warning to procrastinators: It is very easy to spend a lot of time playing with Book Brush while convincing yourself you are doing something productive. So keep an eye out and don't fall into that trap when you should really be writing. At the end of the process we know that by using Book Brush templates, our finished cover is going to be fully compatible with the technical requirements for KDP and other book publishing sites. But the biggest advantage is the range of templates that are available and how you can manipulate them to create a design that is unique to your book. The templates and other images are conveniently organised into genre specific groups.  KDP cover creator offers you about a dozen templates and they are pretty much fixed. You can add your own images, of course, but trimming them is difficult and it is inevitable that your book cover is going to look like hundreds of others, which is where Book Brush offers one of its great advantages. Not only that, but you have an almost unlimited ability to change colours and fonts. The platinum subscription for Book Brush offers the flexibility to remove backgrounds from images, but you may not want to pay for that. Removing background allows several images to be combined to create unique covers. Which is where PowerPoint comes in. If you know how to do it, you can remove backgrounds from images in PowerPoint, save the combined image as a .jpg and then import it into Book Brush ready to use. I’m not going to go into detail about how to do that in this blog. We searched YouTube and found this “how to” video for people who don’t already know. Along with all the templates Book Brush also has access to hundreds of thousands of free to use images which you can apply to your covers but, of course, you can also create or buy your own. They have a wide range of fonts and all the special affects you would expect to see for applying shadow, changing transparency etc. If you want to use a particular font and it isn't available in Book brush, you can import it.  There are also some blogs on the site that could be helpful to you, such as the one we read to discover what fonts work best for which genres and which should be paired together to differentiate between titles, sub-titles and author names. So, what more do you get if you upgrade? With the gold package you get templates into which you can insert your finished covers in suitable formats to use for your social media marketing, cover reveals etc, such as showing the cover in a Kindle frame with accompanying promotional text. That was about all I saw there that was different and not something that I considered to be worth paying for. With platinum you get the ability to create video trailers for your books, by combining either your own video images or using their collection of stock video. To that you can add music or a narration. The package is quite easy to use, can create videos compatible with the different social media platforms and the results look very professional. But it isn’t something we would use a lot so, in our opinion, it didn’t justify the additional $147 subscription fee.  If they offered the opportunity to buy a one-off video package for $10 - $15, we’d certainly use it, but I don’t think the subscription offers value for money unless you’re going to be creating a lot of video trailers. Where Book Brush really comes into its own is in creating paperback and hardback covers. With the wide range of trim sizes on offer through KDP and the wide variation of page counts between books, coming up with a PowerPoint template that works for every book is impossible, so it’s all down to trial and error, which can take hours of work to get right. But Book Brush just asks you how many pages your book has and then creates a custom template for you which is guaranteed to pass KDP’s quality standards. All you have to do is overlay the different content you want to use for your design and, again, you can use their designs and images or create your own. So, overall we are quite happy with Book Brush. It’s easy and quick to learn and you can start producing professional looking book covers within an hour of paying your subscription. We certainly recommend the silver package. Whether you want to pay more for the extra buzzers and bells is down to you. If you would like to know more about Book Brush, click/tap here. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, be sure not miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. We’ll even give you a free ebook for doing it. Just click the button below.

0 Comments

This week we hand over our blog to one of our authors, Robert Cubitt, who has been dabbling in the world of audiobooks. All views expressed by the blog's author are his own and are not necessarily shared by Selfishgenie Publishing  As an Indie author, have you ever wondered if you should turn your masterpiece into an audiobook? I did wonder, so I did some research to see if it was the right thing for me (spoiler alert – it was). First of all, the market for audiobooks in the UK in 2021 was £151 million, up from £133 million in 2020. In the USA the market was worth $4.2 billion in 2021 and is expected to grow to $33 billion by 2030. Just a microscopic slice of either of those pies is a significant amount of money. So, why are more Indie authors not pursuing this avenue for selling their books?  Aside from snobbery (some authors don’t believe that audiobooks are really books) the answer is cost. First of all, audiobooks cost far more to buy than either an ebook or a paperback. In the US an audiobook will cost between $20 and $30 and prices are comparable in the UK. For this reason, many audiobook retailers work on a subscription basis, allowing listeners to download multiple titles each month for around $15 (and the equivalent in pounds).  If you subscribe to Spotify or iTunes, you will already be familiar with this and Audible provides a typical subscription model for audiobooks. In essence it is no different from what KindleUnlimited does for ebooks. The reason behind this cost is that an audiobook requires a narrator, and they don’t come cheap. If you want a well-known actor to narrate your book you can think of a starting price in excess of £3,000 ($3,500) and some audio books use more than one actor: an overall narrator, a male character lead and a female character lead, which further increases the cost. The cost of those voices has to be recovered before either the author or the publisher makes a penny in profit.  But I wasn’t going to be deterred by this, so I went looking for cheaper options – and found them. I’ll be talking about acx.com a lot, as they are the largest distributor for audiobooks. They sell audiobooks through Audible, Amazon and iTunes, which between them control around 80% of the audiobook market. If your audiobook isn’t on acx.com, it isn’t anywhere. But I’m getting ahead of myself. The first thing you need if you want to publish an audiobook is a narrator. So how do you find one of those? And, more importantly, how do you find one that won’t charge an arm and a leg to work with you?  My starting point is the same as for any job I want doing in relation to publishing: fiverr.com. A search for “audiobook narrators” provided me with an extensive list of potential candidates. Each one has posted an audio clip of their voice, so you know what you are getting before you even approach them. If your book is British based you will want a British accent (unless you are Lee Childs, who sets his books in the USA), likewise if you are an American author you will probably want an American accent. You may want to choose between a male and a female narrator. Whatever you want, you will probably find someone to offer it. There’s even one that offers to read a French translation of your book for the French market.  Rates for narrators vary and they quote their prices by 100, 200, 250 words etc so do check carefully what they are quoting so that you can compare prices properly. The narrator I picked out suggested a starting price of £4.54 (around $5.25 at current exchange rates) for 250 words, which is very much at the economy end of the scale. (I will provide his details at the end of the blog.) But his voice sounded good, so I asked for a “custom quote” based on the length of my book. My narrator came back with a quote of $1,800 (about £1,560).  If that makes your eyes water, then I empathise because it made my eyes water too. However, you must remember that, unlike many services, you aren’t just paying for time, you are also paying for talent. But my books have been doing well recently and paying that amount from my recent royalties wasn’t out of the question. However, I wasn’t going to commit to that amount of money on the spot. I messaged back to the narrator to say I would think about it and get back to him. At which point the negotiations really started. My narrator told me he could do it for about half that amount, but with a royalty share option – 50:50. This is a facility that acx.com operates, so the author doesn’t even have to pay the royalties to the narrator; acx.com does that. If you think that is giving away a lot, please remember that 50% of something is always better than 100% of nothing.  So, we agreed $900, which would be paid through Fiverr.com and the rest would be paid in royalties through acx.com. So, just a quick conversion for my British readers, I paid about £780 upfront to my narrator, plus Fiverr.com’s charges. Please note that the royalties scheme has no limit to it. The author doesn’t stop sharing when a certain level of royalties have been reached. It goes on for as long as the audiobook remains on sale. That can mean my narrator receives a lot more than $1,800 if the book is a good seller, which is why some narrators like this way of doing business. But, if the book isn’t a good seller, my narrator (and me) may not make very much from it. That’s the gamble we are both taking.  Don’t be surprised if your narrator asks about your ebook and paperback sales figures before he or she agrees to a royalty share deal. And they may check out the book’s sales ranking on Amazon, so don’t try to fool them. Having never done this before, I decided to find some resources to tell me how it all works. In terms of the technical requirements for the book, I found this helpful check sheet. It gets a bit technical in parts, but it does provide the basics. Most of that is your narrator’s responsibility, but it does no harm for you to know about it too. I then found this video on YouTube which provides a practical demonstration. That is stuff that you as the author will need to know in order to upload your audiobook for distribution.  In terms of uploading your book, it is no more difficult than using any of the self-publishing websites with which self-published authors, like you, will already be familiar. However, there are two things which are very different:

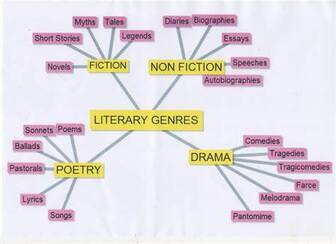

Because I had already decided on my narrator, I didn’t need to get into the audition process. But basically, if you want to look for narrators who are already registered with acx.com (and the vast majority are) you can upload an extract of your book for prospective narrators to audition and bid for the work. You can apply filters for your narrators, such as nationality, language, gender, accent, and general tone of voice you want for your book (serious, dramatic, humorous etc). If you have already decided on your narrator, as I had, you can search for them by name in the appropriate section, and they will be linked to the project.  When you tell acx.com the wordcount for your book, they do a calculation on how long it should take for a narrator to read (a 90k book is about 9.5 hours). In the appropriate section of the site, you can then enter an hourly rate you are willing to pay. Multiply one by the other and you get an indicative cost for your audiobook. I would suggest a starting price of about $50 (£45) per hour. If you don’t get any bids to narrate your book by the cut-off date that you specify (typically 2 - 5 days) you can increase the hourly rate until you get a bid with which you are satisfied. The site pays royalties of 40% for exclusive distribution rights for your book or 25% for non-exclusive rights. I went for exclusive, which gives me 20% and my narrator 20% Having already chosen my narrator, and found him in acx.com’s directory, I filled in the details for the royalties share scheme. This section also asks if you agree to fund some or all of the narration costs. Don’t tick that box if you have agreed a “royalties only” scheme with your narrator, as I had; acx.com doesn’t need to know about the lump sum payment made using Fiverr.com Caution: once you have posted these details you can’t change them. You have to cancel the whole project and start again (as I discovered).  And that’s about it. Your chosen narrator will get to work and provide you with a 15 minute segment, so that you can verify they are narrating your book the way you expected. Once you have signed off on that they will carry on with the rest of the recording and they upload the files when they have finished. You listen to the files to make sure you are satisfied and after that it is no different from publishing an ebook or paperback. Publishing an audio book isn't a speedy business. Firstly you have to wait while your narrator actually narrates your book and it probably isn't their full time job, so they will be doing it in their spare time. Secondly, once it is uploaded there is a lengthy quality review process which acx.com says takes 10 business days to complete but which took longer in the case of my book, for some unexplained reason. Then comes the hard part, of course – marketing the audiobook. Because, just like any other publishing medium, no-one is going to stumble on your book by accident. You have to tell readers/listeners about it, and where to find it. But this is where you get a little bit of a bonus by being on a royalties share basis. Because your narrator has a vested interest in the book being successful and they will probably do some marketing on their own behalf. Can you narrate your own book?  If you think you have the voice for it, then of course you can. But beware, acx.com has very tight quality standards and you may not be able to reproduce these at home. Readers also want a “clean” listening experience, so they don’t want to hear the sound of your children squabbling in the background, or your dog barking at the neighbour’s cat (or both). See the technical checklist I linked to above. So, how successful has my audiobook been?  I have no idea because it has only just been launched. But I’ll be back after Christmas with an update, so be sure to check back. And if you want to find out more about my audiobook version of Operation Absolom, you can download a free extract here. Or you can check it out on Amazon by clicking here. If you are an author who would like to use a male British narrator for your book, then I am pleased to recommend Michael Hajiantonis. You can find him on acx.com under that name or you can do what I did and find him on Fiverr.com using this link. If you would like to get a promo code for a free download of the Operation Absolom audiobook, just email us through our contact address. All we ask in return is for a review and a share on your social media. Good luck! If you have enjoyed this blog and want to make sure you don’t miss future editions, you can sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so. Just click the button below.  It is disturbing to read on social media, especially Twitter, that so many authors struggle with writing a synopsis for their book. After all, they have just written between 80k and 140k of beautiful prose but are struggling to write just one page of A4 that will communicate to an agent or publisher what the book is about. Perhaps, like panic, the under confidence of some authors is spread to other authors like a virus, making perfectly confident writers suddenly doubt their ability. It is about the only explanation I can think of. But rather than try to analyse the cause perhaps, in this blog, I can help authors by offering some practical advice.  The starting point of any task is to establish a goal – something to aim for. Fortunately, agents and publishers have already done that for you, because they know what they want from a synopsis. To put it simply, they want to know what your book is about in as simple language as possible, so that they can be confident that the author knows what it is about. You may wonder about the last part of that sentence. After all, surely the author knows what their book is about, don’t they? Apparently not. The author may think they have written an exciting fantasy/sci-fi/hist fic/YA/whatever novel, but if they can’t explain that in simple terms, the agent (or publisher – I’ll stop using both terms from here) won’t believe that they know what they are doing. "Pick one genre!"  To start a synopsis, you must first clarify what genre it is written for. If you think your book crosses genre boundaries, eg a fantasy that includes a romance, then which genre is it mainly aimed at? In life I have often said that you don’t always have to pick a side, but in writing a synopsis you do have to. Pick one genre! If the romance element of the story is crucial to the fantasy plot, you can cover that later (or vice versa if romance is the main genre). And don’t start getting into sub-genres, the way Amazon categorises books – they have something like 16,000 different genre classifications. In reality there are between 35 and 50 recognised genres, depending on who you ask. Purists would argue that it is an even lower figure, but that is why they are called purists.  Picking your genre is vital because your agent has to know that the book has a chance of making money. Writing in an unfashionable or unpopular genre is going to dispatch your novel to the reject pile faster than a split infinitive ever would. Also, there are many agents who specialise in a specific genre and they want to know up-front that they are the right agent for your book. They won’t waste their time reading your book if it isn’t in their genre. The next step is to write a brief (75-100 word) summary of the plot. It is suggested if you can’t summarise the plot in that few words, then you don’t really know what you have written. To give you some idea of what I mean, try this summary of one of our author’s books.  “Operation Absolom tells the story of a young man, Steven Carter, who enlists in the British Army during World War II. Bored with garrison duties he decides to volunteer for a more adventurous life with the newly formed commandos. In doing so he gets far more adventure than he bargained for and comes close to losing his life in the freezing waters off the coast of Norway. In order to survive, he has to dig deep into reserves of courage and determination that he didn’t know he possessed.” To save you counting, that is 88 words. The key thing about that summary is that it tells you when the story is set (World War II), who the protagonist* is (Steven Carter), what he gets himself involved in (fighting in the commandos) and why he gets involved (seeking adventure). It also tells you that he gets more than he bargained for, which is the source of much of the drama in the plot. The last sentence indicates a degree of personal growth taking place during the story- which means that the character develops as the story goes along.. (FYI you can find out more about Operation Absolom by clicking on the cover image)  The main body of the synopsis is a longer description of 300 to 500 words. The way I go about that is to take each chapter in the book and write a single sentence saying what that chapter is about. Again, using Operation Absolom as an example, here’s what we came up with.

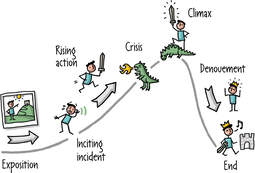

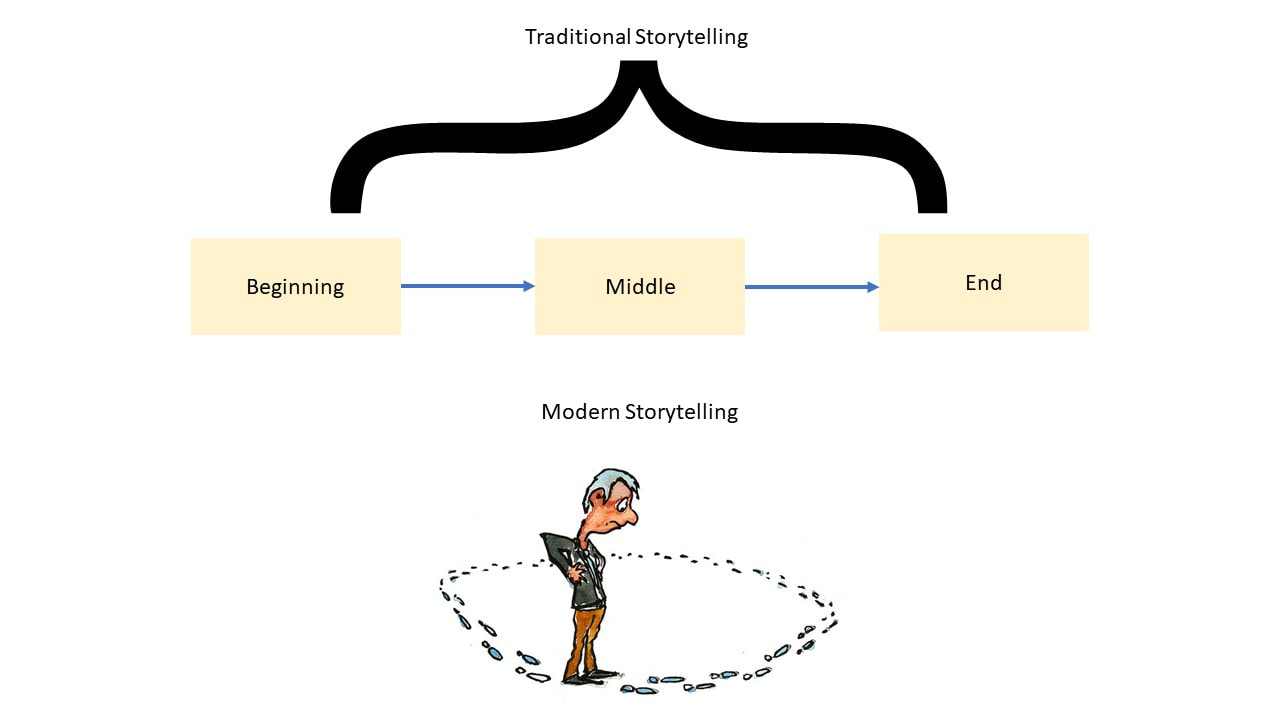

And so on. If there are chapters that just deal with sub-plots, delete those sentences. There is nothing wrong with having sub-plots, but the agent is more interested in the central plot, so confusing things with sub-plots and using up valuable word count along the way isn’t going to help your case. Now join the sentences up into sensible paragraphs, emphasising the major points of the story. If you are familiar with the way story arcs work, with highpoints preceded by build-up and followed by aftermath, then it is important that the description follows the same pattern, so that the agent can see where the high and low points are and therefore get some feel for the pace of the story. This is what we did with the three sample sentences we produced above: “After a conflict with his commanding officer, Steven Carter decides to volunteer for the commandos. His training in Scotland reveals an unconventional approach to soldering that risks cutting his commando career short, but he survives to join his new unit, 15 Commando. At once he is pitched into training for a top secret operation, Operation Absolom.” I’ve used only 57 words to cover almost a quarter of the book, leaving me plenty of word count still available to deal with the more action packed parts of the book. Note the hints and teasers used to tantalise the reader eg conflict, unconventional. If you are struggling to keep below the 500 word level, then you are probably including non-essential information.  As well as sub-plots, don’t include: - Dialogue, - Descriptive passages, - Inconsequential characters, - Backstory (you may hint at this with phrases such as “troubled past” or “difficult family life”), - Moralising messages - Metaphors (speak plainly). If you include any supporting characters, refer only briefly to their role in the plot and their relationship to the protagonist, eg Sam is Frodo’s best friend and would rather die than be left behind in the Shire. Later in the story he takes on greater significance in making sure that Frodo fulfils his purpose.  Beware the search for perfection! Beware the search for perfection! The final, short, paragraph just closes the synopsis off in a neat and tidy manner. Tell the agent what the total wordcount is and if you have any plans for a sequel. If the sequel is already underway, say that. If book is intended to be part of a series, say how many books you are planning for it (agents like to know they can expect a long term relationship with an author (with accompanying long term income)). Finally, beware of seeking perfection. You can spend a hundred hours on drafting and re-drafting 40 versions of a synopsis and it probably won’t be any better than the second or third draft. The agent doesn’t care if the synopsis isn’t perfect because, unlike the book, it isn’t something that is ever going to be published. The agent expects it to be properly spelt and grammatically sound, that is all. What they are really interested in is whether or not the story sounds interesting enough to read all the way through. How do you know if your synopsis is good enough? The same way as you know your book is good enough. Show it to someone whose opinion you value and ask “Would you read this book based on this synopsis?” As always, don’t rely on family or friends to be honest with you – they love you and tend to say what they think you want to hear. Use someone who can be relied upon to be impartial, such as your beta readers. If you haven’t got anyone to whom you can show your synopsis, send it to us. You can find our address on our “Contact” page. Make sure you tell us that you just want some feedback on it, so we know you aren’t submitting your book (though we may invite you to submit it if we like the sound of it). * Always use the word “protagonist” in a synopsis, not “main character” or “MC”. It is more professional sounding. There is only ever one protagonist. Anyone else is a “supporting character”. For the same reason the “villain” is always the “antagonist”. If you have enjoyed this blog and want to make sure you don’t miss future editions, you can sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so. Just click the button below. Disclaimer: This blog talks a lot about Amazon, but we are not connected to them in any way other than they sell our books. We are definitely not being paid to mention their name and we are not recommending Amazon. We are just recounting our experiences in the hope of passing on some of the knowledge we have gained.  As an author who sells through Amazon, you will know all about “sales ranking”. If your book sells, the ranking improves and people are encouraged to buy your book because other people have bought it. And if your ranking is low, people think your book isn’t any good because other people aren’t buying it - but that is flawed logic. Just because a book isn’t selling it doesn’t mean it isn’t any good. It may just mean that nobody knows about it (we blogged about advertising last week, so we’re not going to go back over old ground). But you won’t convince some readers that a book is good if it isn’t selling and there’s not much we can do to change that mindset.  We have been fortunate over recent weeks that several of our books have sold well and their sales rankings have improved exponentially. Instead of being in the 7 digit ranking range they are into the lower end of the 5 digit range – and are still climbing. That’s for their overall, ranking of course, not the category ranking. In some obscure categories its possible to be the No 1 bestseller just by selling a single copy. So that isn’t a good comparison for the purposes of this blog. But we believe our books’ rankings should be higher still and we also believe that the way Amazon calculates their rankings doesn’t take into account a whole raft of “sales” through their own platform. I’m referring to Kindle Unlimited (KU) pages read. While they may not be direct sales, the way that a book is sold, the reader is still paying to read the book through their KU subscription and the author is still getting an income from those page reads. So, it is our contention that those page reads should be included in the calculations of sales rankings, which are an indication of the popularity of the book. KU page reads account for about two thirds of all our sales income (more for some individual titles). It is the equivalent of a lot of books sold. But Amazon doesn’t count them and there is no valid reason, as far as we can see, why they shouldn’t. In fact, it might actually be to Amazon’s benefit to include KU pages read, because the more popular a book, the more copies it sells and the more money Amazon will make from those sales. They are, effectively, depriving themselves of potential income with their current policy. I’ll use just one of our titles as an example of what we mean. "Our guestimate is that it would put the book into the top 1,000" But before we go on, a quick bit of jargon busting, for those of you who might need it. KENP means Kindle Edition Normalised Pages. It is the number of pages that Kindle Direct Publishing uses to calculate an author’s royalties for KU downloads. The more pages read in a book, the more the author gets paid. It is used to factor in the different font sizes and line spacings that authors use, which makes direct comparisons between the number of pages in a book problematic. We’re not sure how the KENP for a book is arrived at, but we suspect it may be based on character or word counts Mansplanation over, back to the blog.  Operation Absolom is the first book in Robert Cubitt’s “Carter’s Commandos” series. In July 2022 it sold 11 copies. This elevated it to around 30,000 in the Amazon rankings at the time. Although Operation Absolom is 296 pages long in paperback, its KENP is 437 pages. During July 2022, 19,215 KENP pages were read using KU. Divide 19,215 by 437 and it works out at 34 complete books. So, if 11 books sold gives Operation Absolom an average sales ranking of about 30,000, what would another 17 books give it if they were included in the figures? (BTW it actually peaked at around 10,000 - 7/7/22) Our guestimate is that it would easily put the book into the top 1,000, which makes the book look very popular indeed – as it is in reality. OK, we’re not talking J K Rowling or Lee Childs popular, but it is a lot more popular than a million other books on Amazon. "Perhaps weight of numbers might encourage a shift in policy" We could quote similar figures for the rest of the Carter’s Commandos series, because once people have read the first book it is clear they are then reading the rest of the series. But you get the idea from the one title we have used as an illustration. But it doesn’t look like that on Amazon. So, what can we do about it? We have already emailed Amazon to ask them why they won’t change the way they calculate their sales rankings. After all, they have all the data to hand and doing a new calculation that includes KENP would hardly be rocket science. This was their reply: “Sales rank is determined by a number of different inputs and may change over time. Amazon is constantly working to improve the quality of information available to our readers and authors. Please note that Sales Rank fluctuates every hour in line with customer demand and in relation to the demand for other books, both of which may vary based on factors such as popularity of new releases, seasonality, etc. Rankings reflect recent and historical activity, with recent activity weighted more heavily. Rankings are relative, so your sales rank can change even when your book's level of activity stays the same. For example, even if your book's level of activity stays the same, your rank may improve if other books see a decrease in activity, or your rank may drop if other books see an increase in activity. When we calculate Best Sellers Rank, we consider the entire history of a book's activity. Monitoring your book's Amazon sales rank may be helpful in gaining general insight into the effectiveness of your marketing campaigns and other initiatives to drive book activity, but it is not an accurate way to track your book's activity or compare its activity in relation to books in other categories. Thanks for taking time to share your thoughts about considering KENPC in sales ranking calculation. Customer feedback like yours is very important to helping us continue to improve our products and services. I appreciate your thoughts and will be sure to pass your suggestion along. Please refer to our Sales Ranking Help page for information regarding Sales Rank - https://kdp.amazon.com/help?topicId=A21KM4BNAD42EJ”  Amazon sales data - just the tip of the iceberg. Amazon sales data - just the tip of the iceberg. We emailed back to them, saying that they were undermining their own reply. If tracking the effectiveness of marketing is an important use of sale rankings, then Amazon should surely be doing its best to maximise its utility by including KENP data, because that fluctuates in response to marketing activity as well I also pointed out that by not including KENP, they were showing customers the tip of the iceberg, not the whole iceberg. They did reply once more, but only to provide platitudes. But if you are an author and your books are read using KU, then this is something that you should be concerned about as well. So why don’t you add your voice to ours and ask the same question? Perhaps weight of numbers might encourage a shift in policy Let’s face it, you have nothing to lose and your book’s sales ranking have everything to gain. But while we are on the subject of KU, would you like to help other Indie authors to maximise their income? I hope you said “yes” because it only takes a few seconds and will cost you nothing. When you get to the words “The End” in a book, there are often a few more pages left in it after that. They may be a preview of another book or an advert for other titles. It doesn’t matter. Just keep on swiping until you get to the actual end, so that the author gets paid for every last one of those KENPs. It may only be a few pennies (or cents) extra, but they add up. Even if the book wasn’t to your taste and you didn’t finish it, which is hardly the author’s fault, you can make sure they get full recompense for their work by swiping through to the end anyway. As I said, it costs you nothing but a few moments of your time. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative (both we hope), be sure not to miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. We'll even send you a FREE ebook for doing so. Just click the button below. Once again we turn our blog page over to a guest blogger. The views expressed are those of the blog's author and don't necessarily represent the views of Selfishgenie Publishing  Have you noticed how books are all starting to conform to a pattern these days? After reading the start of a few books quite recently I rejected them, but it was only after I rejected them that I started to realise that the reason I rejected them was because they weren’t conforming to the pattern. Therefore, I wasn’t prepared to carry on reading them. Which was most unfair on the authors who had invested so much time in writing them. So, what is the pattern? It’s the habit many authors now have of hitting the reader between the eyes on page one of the book, with some sort of action scene, before dialling down the action to properly introduce the characters and develop the plot. They then pick up where the action left off and continue the story in a more linear fashion. I have to plead guilty with regards to my own books. It doesn’t just apply to books that are action focused. Romances, too, sometimes start in the middle before returning to the beginning. So, has this always been the way books were written? Going back deep into history, to the start of my own reading, I remember that stories happened in a predictable order. There was the beginning, where the characters were introduced and the starting point of the story was established, then a middle, where the plot was developed, then an end, where the climax was reached and everyone lived happily ever after. This allowed the author to develop their characters before launching them into their adventures. Who could imagine “Pride and Prejudice” being a success if we didn’t know all about Elizabeth Bennet’s personality from the very start.  If you think about the fairy stories of childhood, they always conformed to the beginning, middle and end pattern. We don’t first encounter Snow White breaking into the Seven Dwarves’ house, then go back to find out that she was sent out with the huntsman to be murdered on the orders of her wicked stepmother. Similarly, we don’t first encounter Cinderella running away from the ball, losing her glass slipper on the way, then go back to the kitchen to find out she is being bullied by her wicked stepmother and the ugly sisters.. Of course, those stories are for children and a child’s unsophisticated mind couldn’t follow a story told any other way. But what we learn as children tends to stay with us for life. As we grow up the stories still follow the beginning, middle and end paradigm until we reach adulthood. Then mayhem ensues.  The problem with this traditional style of storytelling, of course, is that it takes time to introduce characters, explain who they are and what they are doing. I remember having been bored silly by “The Warden”, a novel by Anthony Trollope and considered to be a classic. The reason I was trying to read it was because it was a set book for my English exams and I was supposed to be learning how to use language and how to tell a story properly. Today Trollope’s book might never find a publisher, because it takes so long to get going (no great loss if you ask me). The same could be said of many other books that are regarded as classics. So why this change in the approach to storytelling? Well, literary agents are partly to blame (or are they?). When an author wishes to submit a book to an agent in order to try to get a publishing deal, the first thing they do is go onto the agent’s website and read the submission guidelines. These are invariably the same. Submit no more than the first 10,000 words or the first 3 chapters. If the agent likes what they read, they will ask for more. If not, they won’t. Even when it comes to publishers who accept submissions direct from authors, the word limit is usually still applied.  So that’s it guys and gals. If you can’t grab the agent’s attention in those 10,000 or so words your book will be rejected. So, in order to deal with that the author tries to inject some action into the first thousand words in the hope that the agent reads on. The result is that the middle of the book, or at least part of it, gets stuck in before the beginning. However, is it really the agent’s fault? After all, isn’t the author making a rather large assumption about what the agent wants to read and is tailoring their book on the basis of that assumption. Maybe the agent actually wants to see how the characters are developed and how the plot unfolds. Maybe that is why so many authors receive rejection letters. Maybe we are making our submissions based on false assumptions. If you are an agent or publisher reading this, perhaps you’d like to comment.  Then there is Amazon. Their “look inside” feature gives the purchaser the opportunity to read a couple of thousand words of a book before they purchase it. This is to match the experience of the “browser”; the reader in the bookshop or library who has the time to spare to actually read the first few pages of the book before they decide whether or not to borrow or buy it. So, again, the author may set out to grab the reader’s attention so that they don’t put the book back down again. But again are we, the authors, usurping the process by making the assumption that the reader won’t borrow or buy our book if we don’t hit them between the eyes on the very first page. It is said that the first line of a book must be an attention grabber. That’s fair enough, but that doesn’t mean that the author then has to launch into climactic action before the reader even knows who the characters are.  As part of the research for this blog (yes, I do research) I read the ‘look inside’ portion of Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick”. This, of course, is reckoned to be another classic. But based on what I read, I wouldn’t buy it. To be sure, Melville’s use of language is beautiful, but in the opening pages of the book not a lot happens. The reader isn’t even told that a whale is involved. We don't even find out who Ishmael is or what he has to do with the story (not a lot, as it turns out). So, is it therefore not the reader’s fault that the whole nature of storytelling has changed? We expect instant gratification. We want the action to start on Page One, and if it doesn’t we put the book down and move on.  Thinking about this made me think about films (movies) and the way they now tell their stories. We are used to James Bond films, for example, where Bond is always in mortal combat with an enemy in the opening scenes of the film, well before the title music starts up. Other films also use this technique. So, maybe, in our minds, we have started to think that is how our stories should be told. We, too, are putting the action in before the metaphorical title music. So, when an author goes back to the traditional beginning, middle and end format for writing, we think it a little bit odd. Is this what guided my decisions to reject certain books? Or is it just me? I may have been rejecting masterpieces, simply because I didn’t have the patience to let the author tell the story properly. I have had the same conversation with my wife when new TV dramas start up. It’s a bit boring, she’ll say, and my reply will be that we have to establish who everyone is first and how they connect together.  Again, thinking of TV crime shows in particular, they often open up with a dead body and it takes the rest of the story to find out who the dead person really was, and all their little quirks and foibles which led them to being bumped off. Along the way we also find out about the police officers who are investigating the death, but not until after the body is found. Would I still watch the programme if it unfolded any other way? I can hardly complain that a character is underdeveloped if I won’t give the author time to develop him or her. I can’t complain about the plot being difficult to follow if I don’t give the author time to explain what is happening. This is particularly so when it comes to back story. It is like trying to tell the story of World War II without first telling the reader who the Nazis were. Will I be changing the way I write my own stories as a result of what I have deduced? I don’t know. I rather like hitting the reader between the eyes on Page One. I don’t do it in every book I have written, but I have to admit to doing it in the majority of them. Judge for yourselves whether it is the right technique. Just click on the “books” tab at the top of this page to find out more. If you enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, be sure not miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. Just click on the button below. We'll even let you choose a FREE ebook for doing it. Do you fancy being a guest blogger for Selfishgenie Publishing? Just email us and tell us what you would like to blog about. Find our email address on our "Contact" page.

Once again we are turning our blog page over to a guest blogger. All the views expressed in this blog are those of the blogger and are not necessarily representative of the views of Selfishgenie Publishing.  Why do it? Why put yourself through all the trials and tribulations of writing a novel, searching for an agent, then possibly having to do all the work to self-publish if you can’t attract an agent? I have applied some thought to this and have come up with the following list of reasons. It isn’t exhaustive, so please feel free to add your own suggestions in the comments below the blog. 1. You like writing. I know that this sounds obvious, but I have actually met authors who have told me that they love being an author but hate all the writing that goes with it. Sorry, that will never work out. You can test yourself on this. If, suddenly, an hour of your time were to come free, which would you rather do (A) watch something on TV or (B) sit down and try to write something. If the answer isn’t (B) then you are never going to be an author.  2. You have a genuine talent. When you first decide to write you may not know if you have the talent for it or not. Even when you have written your first book and shown it to friends and family you still can’t be sure, because friends and family often want to be kind and so they say kind things about your work. But if you do have a talent then it is vital to express it, or frustration is the only possible outcome. The first review on Amazon (other book selling sites are available) that is submitted by a stranger will tell you if you have a talent or not. But there are two different forms of talent that make a good author. The first is a talent for story telling – and it doesn’t have to manifest itself in the written form. If you are the sort of person who is able to make up stories for the entertainment of others, you have this talent and you are halfway to becoming a successful author. The second talent is the actual writing part. Being able to construct sentences that grab the reader’s attention and provide them with the emotional input they crave. Being literate in the grammatical sense helps, but that can be sorted out by a proof reader or editor. 3. You love reading. Reading and writing go hand in hand. All real authors start off as avid readers. The best books inspire us to have a go, while the worst books inspire us to try to do better ourselves.  4. You live somewhere where there are harsh winters. I’m serious. It’s far easier to sit indoors and write a thousand words if the sun isn’t shining outside. Even small outdoor distractions, such as tidying the garden, get in the way of writing. If you live in the sort of latitudes where it is dark for 18 hours out of 24 (or even longer) then so much the better. 5. You have something you want to say. We all have opinions, but some have stronger feelings about things than others. Writing them down in the form of a novel allows you to imbue your character with your opinions while also telling a story. However, there is a downside to this. You may be alienating all those potential readers who disagree with your opinions. While you may believe that you are right, they have the right to disagree with you.  6. You want to expose something that needs exposing. Making an issue part of your plot allows you to expose a problem or a scandal. If your readers are intelligent (they probably are, otherwise they wouldn’t be reading books, they’d be playing computer games) they will see where the fiction ends and where the reality starts. You can often reach a far larger audience with a novel than with a polemic. To Kill A Mockingbird did far more to expose racism in the USA than any number of learned treatises. 7. You want to entertain people. We can’t all sing or dance or play the piano, but if you can write a decent story, you can be an entertainer. Story telling as a form of entertainment goes back far further in history than music or dance. 8. You have to get the stories out of your head. So many good ideas for stories, but they are no good stuck inside your head. They just nag and nag at you. So, tell the stories and stop them nagging you.  9. It’s cathartic. Expressing yourself artistically (yes, that’s what authors are doing) makes you feel better. Getting your demons out of your head and onto the paper prevents them from praying on your mind and threatening your sanity. 10. You like telling lies. Authors tell lies for a living. The best of them are able to make you believe their lies so well that they can transport you to a whole world that they have created out of their lies. Tolkein, Pratchett, Douglas Adam, Richard Adams, the list goes on but the one thing these greats have in common is that their worlds didn’t exist, but they made us believe in them anyway. They could sell snow to an Eskimo. And One Reason Why You Shouldn’t Become An Author.  1. You want to make lots of money. Sadly, you probably won’t. Even if you sell quite a lot of copies, your publisher, agent, printer, retail outlet etc will all take a cut. Typically the author only gets about 10% of the gross income from sales and then the Inland Revenue want a cut of that. For a £9.99 paperback ($11.50 approx) the author won’t get much more than 80 pence. To make the top 100 best seller lists you have to sell at least 100,000 copies, which means the author might get £80,000 before tax. But the majority of authors, probably 90% of them, will never sell more than 1,000 copes, so earnings expectations are very low. According to The Guardian most authors make less than £600 a year. Given that you have probably invested about 1,000 hours in writing your book, that isn’t a very good return. It’s certainly below the hourly rate for the so-called Living Wage. A meagre 1.7% of traditionally published authors and 0.7% of self-published authors make in excess of £70,000 ($100,000 approx). The article is a bit old now, but the fundamentals of publishing haven’t changed since it was written. The big money from books comes from film and TV rights. If your book attracts that attention then the sky is the limit, but again, that won’t happen for about 90% of authors.  How many authors are out there writing away and how many of them will hit the big time? Well, accurate figures aren’t available because most data is based on sales and if no sales are forthcoming you won’t be counted. Then there are the thousands of authors who are still working away in the bedrooms, kitchens or sheds to complete their first manuscript and can’t be counted because they haven’t yet broken cover. But put it this way, over a million books are uploaded onto Amazon each year, the vast majority by by self-published authors and then you have to add on those that are published by small, on-line publishers. Whereas the total output of the big publishing houses, who dominate the market, is between 1,000 and 2,000 books per year of all types (UK figures). Even with the backing and marketing budget of a major publishing house most of those books will sell less than the magic 100,000 copies needed to make it onto a best seller list. In Susanne Collins’s The Hunger Games the supporters always say to the combatants, “may the odds always be in your favour”. The truth is that in book publishing, the odds are always stacked against success.  Ignore all those claims made by some authors of being “Number 1” on Amazon’s best seller list for such-and-such a category. The way Amazon works you can make it to number one with the sale of half a dozen copies in a day, even less in some obscure categories. You’ll only be there for a day, perhaps even for an hour, but that’s long enough to do a “screen save” to share on Facebook or Twitter. if you doubt me, re-read Reason 10 above. Many writers will never make anything from the sale of their books. That doesn’t mean that they are bad books. How would anyone know if they haven’t read a copy? No, the authors don’t make any money because readers like to stick with the tried and tested. They may read a book that is recommended to them by a friend or relative, but they don’t often go seeking out new authors for themselves. The friend or relative probably bought their copy because it was reviewed in a newspaper or magazine, channels that are securely stitched up by the big publishers. Hey – who said that the world was fair? Show me the contract! That is why authors are always asking for reviews. So if you, as a reader, do find a new author and, if you like their book, please consider sharing your discovery by writing a review. So, if you are going to become an author, do it for the love of writing because it is probably the only reward you will ever get. And for those very few of you who will one day hit the big time – don’t forget the little people! If you have enjoyed this blog and you want to be sure of not missing the next one, just sign up for our newsletter. We promise not to spam you and we'll even let you choose a free ebook for doing it. Just click on the button below. And if you would like to be a guest blogger for us, just send us your blog idea. You can find our email address here.

A while ago, in this very blog, I made an offer to review books for other authors. It was intended as an act of solidarity to undermine the leaches that are preying on the writing community by offering dubious quality services in exchange for even more dubious quality benefits - and all at a price. I should have thought it through a little bit more. It isn’t the work involved. If I was worried about that I would never have made the offer in the first place. No, it is that there are so very many poorly written books out there and when you make an offer to review books you have to read them first. The problem is quantity versus quality. There are more people writing books today than ever before. When Covid struck (and a recession earlier in the century), writing a book would seem like good way to generate a new income. The cost of entry into the market is as low as the price of a pencil and a notepad, though a computer of some sort makes life much easier. The truth is that very few authors make enough money to live on, but very few of these new authors would actually know that.  When satellite, cable and free to air digital TV came along I made a personal prediction that the quantity it offered would come at the cost of quality. It is a prediction that came true. While there are good quality programmes on some channels, once you get away from the big name providers you are into a world of repeats, reality TV and pseudo reality. Most of it fits neatly under the heading of "junk TV". The same applies to writing. Quantity comes at the expense of quality. Anyone who can write 80,000 words (it is frequently a lot less) can click on the “upload” button on Amazon, Smashwords, Kobo, Lulu et al and hey presto, they’re a published author. Now, don’t get me wrong. I have read a lot of very good books by Indie authors and those published by small, online publishing houses. I’ve even reviewed some of them in this blog. They deserve better than the publishing industry gives, simply because the big publishers, hand in glove with literary agents, have such a strangle hold on the industry, which means that the majority of authors never have a fighting chance of hitting the big time.  No, the problem is that so many people think that they can write a book when, really, they can’t. Before I go any further, I’m not going to mention any authors or book titles by name. It isn’t fair that I damage their prospects for sales by bad mouthing them in a blog. I’m not a big believer in karma, but I also don’t want to run the risk of retaliation. Let's face it, when it comes to sabotage, these authors have done such a great job themselves. I’m not talking about the “nearly” books that a half decent editor could help the author to lick into shape. The underlying talent in those books shines through and as an author myself I’m willing to tolerate the sentences that don’t quite come across as well as they might, the bit of dialogue that is a little bit clunky or the loose end in the plot that isn’t quite tidied away. All authors know we would write those books differently, but the point is that they aren’t our books, so the author has the right to tell their story the way they want.  What I’m talking about is the book that should never have been written in the first place. The “it seemed like a good idea at the time” books that had no chance of ever making it to a satisfactory ending. These are the books filled with characters that are so badly written that to describe them as one dimensional is to ascribe one dimension too many. The books so lacking in emotion that you would think that the world was filled with emotionless robots rather than with real people. It is the latter which bothers me the most. Readers engage with characters they care about. They will want to read about them. They will want to turn the page to find out if they succeed or fail, love or lose, live or die. Readers care about them because they can identify with them and they identify with them because they understand them. So why couldn’t I identify with any of the characters in these poor novels? Basically it was because the authors told me so little about the characters. Oh, we get plenty of physical descriptions, to be sure. I was also given plenty of plot to read about, some of which was inventive, but much of which had been done before. To make me want to read on, I needed something to care about, and wasn’t given it. I ended up questioning my reason for reading the books. Why should I care about these characters? I don’t know them; I feel nothing for them.  OK, they may be dangling above a fiery pit, just about to get burnt to a crisp, but do I care? Not really. The authors gave me no reason to care. They are just names on a bit of paper (or letters on the screen of an e-reader). They mean nothing to me because the authors haven’t told me anything about them to make me care. Like the guy on the left, they're just a caricature. When I think back over all the books I have ever read that I really enjoyed, the common factor is that they had strong protagonists. I don’t mean strong in the “wading through fire to rescue the damsel in distress” type of strong. I mean emotionally strong. Their authors made me feel every pang of emotion that you would expect a real person to feel. This is what worries me about the authors who are writing such poor books. Are they not people too? Do they not love? Do they not feel fear? Do they not feel happy or sad? To read their books you would think that the answer was a resounding “no”. If someone can’t write about emotions then I would suggest that they shouldn’t be an author, because to be an author you have to live with emotion every time you sit down to write. I don’t know about other authors, but when I stop writing at the end of the day I sometimes feel as though I’ve been through an emotional mangle; crushed and wrung out. If I can’t make myself laugh or cry then how am I ever going to make my readers laugh or cry? If I can’t make myself worry about what will happen to my characters, how can I expect my readers to worry about them?  Another problem that I have encountered in recent books is a lack of drama. Drama comes from conflict and if there isn’t any conflict in the story there will never be a story worth reading. Even romantic stories have a conflict at their heart. It is the conflict that prevents the romantically entwined characters from being happy together, at least not until they have resolved the conflict so that they can live happily ever after. This means that the characters must have something meaningful happen to them early in the story. Something that will expose their emotional state and tell me who they are, deep down inside. I have to say that some of the books I refer to have garnered 5 star reviews on Amazon and Goodreads, which is rather worrying. Either the readers who posted those reviews are less critical than me, or the reviews aren’t genuine. I am well aware that not every reader will enjoy every book to the same degree. One person’s 5 star read may be another reader’s 4 or even 3 star. But I can’t believe that 20 or 30 people gave 5 stars to the book I would struggle to award 1 star. It defies logic. I think the problem for some authors is the market testing of their books. They ask friends or family to read them, rather than asking for criticism from somebody independent. However well-read friends and family may be, at heart they want to be seen to be supportive of the author, so they say nice things about the book even if it hasn’t got many redeeming features. Consequently, the author gets a false sense of the real quality of their work and they publish based on that. They may get away with it once and sell a few copies, but no one will be returning to read the sequel. In the meantime, if you have written a book that you think is better than the ones I have talked about above, I’d be happy to review it for you. I really, really would like to be able to post a 4 or 5 star review for someone. And if you think I’m an arrogant know-it-all who wouldn’t recognise a good book if it jumped up and bit me on the nose, then you can say as much when you read one of my books and post a review of it. You can find out more about my books by clicking on the “Books” tab at the top of this page. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then be sure not to miss the next edition. Sign up for our newsletter by clicking the button below. We'll even send you a free ebook if you do.  How long should a book be if the author wants it to sell? I had better state up front that I’m not going to attempt to actually provide a definitive answer to the question I have posed. I’m entering into what might be regarded as a philosophical discussion on the subject and any views I express are merely opinions. But it is quite an important question because the answers, right or wrong, may strongly influence whether or not a reader actually purchases a book. If you use Google to try to find the answer you’ll get various opinions. But, generally, a novel is expected to be between 80,000 and 120,000 words. This is based on hard copy books, of course. Less than 80,000 words and it’s going to look pretty malnourished sitting on the bookshelf in W H Smiths (or Barnes and Noble) alongside its fatter neighbours. Size gives an impression of value for money, even if it is no guarantee of quality of writing.  Once you get over 120,000 words, however, the publisher has a different problem. Paper costs money and profits will be reduced if publishers have to spend more money on paper but still have to charge the same price for the book in order to remain competitive. Most books sell at the same retail price regardless of size; about £18.99 (call it $20) for a hardback book and £9.99 for a paperback. Those prices are for bestselling authors, of course. Kindle books can run from 99p right through to marginally less than the price of a paperback, depending on how famous the author is. There is also a psychological factor. A thick book looks challenging. Maybe it’s so thick because the author has used a lot of big words. Maybe it will take too long to read and I’ll get bored with it. Maybe it’s so long because it’s very complex and I don’t want to spend a lot of time unravelling a complicated plot. Who knows what people might think when faced with a thick book!  While it would be nice to think that readers buy books solely based on the quality of the writing there has to be other factors involved. It can be the only explanation for some of the dross that makes it into best seller lists alongside much better written books and why some very good books never make it. For example, let’s say that a new author publishes their very first book. None of the reading public will ever have seen the author’s name before and can’t have read any of the author’s work, so how will they decide whether or not to buy the book? There is no doubt that marketing plays a big part in this. If the author is published by a major publishing house the publisher will put a lot of money into getting the name of the book out there in front of the reading public. Adverts have to be paid for; review copies have to be sent to newspapers, magazines, radio and TV stations etc. Authors are sent on book signing tours etc.  Best selling "author" Katie Price Best selling "author" Katie Price Based on the marketing blurb, readers may take a chance and shell out some of their hard earned, but in effect they are buying the publisher, not the book. And it works; Katie Price has sold a lot of very poor-quality books. Well, her ghost writers have anyway; she just gets the lion’s share of the royalties. But that doesn’t account for why some books released by smaller publishing houses, or even self-published books, also make it into best seller lists despite the minuscule amount of money spent on marketing them. The readers’ decision won’t be based on the quality of the author’s writing because, with a first book, they can’t have read any previous work on which to base that decision. It is also unlikely to be based solely on the few pages that Amazon allows the potential buyer to read using their “look inside” feature. As both a reader and an editor I know that a promising first few pages doesn’t necessarily lead to 300 good pages. Many authors, even quite well-established ones, are unable to maintain their writing quality for that long and some start to stumble after just 20 or 30 pages. By 50 pages I’ve already binned the book and gone looking for something better written.  Some Indie authors will already be aware of this phenomenon. Having submitted an extract as per an agent’s submission guidelines, they get a request for the full MS. They are elated, naturally, but then brought down to Earth with a bump when the full MS gets rejected. Learn from that – because what the agent is effectively saying is that you couldn’t maintain a consistent quality of writing for a full-length book. So, if the decision isn’t going to be based on the quality of the writing, what is it going to be based on? You would think that price might have something to do with the decision, but it doesn’t appear to do so. When it comes to the price of books we live in a strange world. A pint of beer costs around £4 and a large glass of wine (is there any other sort?) over £5. A self-published e-book, however, will retail for anywhere between 99p and £5 depending on the author’s knowledge of pricing strategies and their vanity. Now, which is going to last longer and offers more potential for enjoyment, the pint of beer/glass of wine or the book?  Well, let me put it this way. In my experience, after 6 months I find it easier to recall a good book (or even a bad book) than I do to recall the qualities of a specific pint of beer or a specific glass of wine. There is another factor involved here as well. If I really enjoy a book, I may go back a few months or years later and read the same book a second time. I’ve read Lord Of The Rings far more times than is healthy for a grown man. But I can’t go back and enjoy the same pint of beer or glass of wine again, not for free anyway – I have to buy another one and, thanks to inflation, it will cost more. So, if people won’t shell out the paltry sum of 99p to read an author’s first book what other factors are there?  Leo Tolstoy Leo Tolstoy I go back to my argument about the word count. Is the reader truly getting value for money, or will they feel intimidated by the “thickness” of it? War and Peace is about 590,000 words long. When Tolstoy first had it published it was released in 4 volumes and a 2 part epilogue. If you want to buy a modern copy it would be more likely to be published as a single volume. In value for money terms you would think that it would be flying off the bookshelves, but it isn’t. Why not? It’s an acknowledged masterpiece after all. Well, perhaps people feel intimidated by its size. Let’s look at a more modestly sized classic, also by Tolstoy: Anna Karenina. Not many sales for that these days though it is perhaps one of the greatest romantic stories ever told. Length? 350,000 words. Hardly lightweight. Remember, I am also talking about e-books here, where you can’t “see” or feel the thickness of the book.  But you can. Because Amazon helpfully tells you, as part of their product description, how many pages long the book is As a guide, 80,000 words gives you a paperback book of about 290 pages, so 120,000 words would be about 435, big enough to qualify as a “blockbuster” in the Arthur Hailey mould. The sort of book that will not only last you for a whole holiday, but also for the cancellation of your flight due to a volcanic eruption and a 24 hour rail strike when you get back to the UK. The Kindle version of Arthur Hailey’s “Hotel” is actually 485 pages long. Perhaps that’s why he rarely features in the best seller lists any more. That and the fact that he died in 2004.  The sad truth is that the attention span of some readers isn’t that great. They’ll read 300 pages but 301 will defeat them. That presents the author with something of a problem. Do you disregard those readers and concentrate on those that will stay the course, in which case you are placing an artificial ceiling on your sales volume. Or do you take another course of action? Maybe you do what many authors are doing these days and write your books as a series; telling the story in 300 page chunks. You wouldn’t be the first: remember Tolstoy and War and Peace? It’s now common practice and one I have adopted for 2 separate series I have written. There can be no doubt that the margins for success for the new author are very narrow and seemingly quite arbitrary. It therefore makes sense, to me at least, not to do anything that might put the potential reader off buying a book and that includes thinking about exactly how long the book should be. Let’s face it, the average story could be told on a single page of A4, yet we expect a bit more than that. So the book should be neither too short (poor value for money) nor too long (too “weighty”). For me that means between 80 and 90,000 words. It’s entirely up to other authors where they draw their lines. If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, be sure not to miss an edition by signing up for our newsletter. Just click the button below. And if you do - we'll send you a free ebook of your choice (from those we publish, not from the entirety of the publishing world). Once again we are featuring blogs by guest bloggers on a wide range of subjects related to reading and writing. All the opinions expressed are those of the blogger and are not endorsed by Selfishgenie Publishing. Enjoy!  One of the questions most writers get asked is “where do you get your ideas from?”. While it’s a predictable enough question, It’s also one that’s easily answered. Ideas are all around us, we just have to look and listen and then let our imaginations take over. One of my earlier books was “The Girl I Left Behind Me”. The title came first. It’s the last line of the chorus to a traditional song and was used in the soundtrack of three John Ford westerns about the US Cavalry, titled Fort Apache, She Wore A Yellow Ribbon and Rio Grande. For some reason the tune popped into my head one day and I couldn’t shift it. But then it occurred to me that it would make a great title for a book. I quickly Googled it to make sure no one else had had the same idea (they appeared not to have) and then put it into my list of book ideas and let it ferment for a few weeks.  It’s the fermentation that is important here. I had a title but no idea what to do with it, so I let my unconscious mind work on it. I also looked up the origins of the song and found that it was traditional, probably 17th or 18th century British or Irish and had been popular with both sides during the American Civil War. Its rhythm makes it very suitable as a marching song which is why it has come down to us via a military route. Letting that information ferment alongside the title eventually gave me the idea of writing a story set in modern times about two young men who are born just a few streets apart but who go off to war to fight on opposite sides and who leave their "girls" behind them. The story is as much about the two women as it is about the men. I won’t give any more away, just in case you want to read it, but I’m sure you can see that once I had the basics mapped out, writing the story became something that was achievable. Not only that, but one of the characters I created for the book went on to feature in a sequel.  I have an ever-lengthening list of ideas for books that may, or may not, eventually see the light of day and they have come to me by a number of routes. They say that everyone has a book inside of them. American author Jodi Picoult added the rider “the problem is winkling it out” while British writer Christopher Hitchens is credited with adding “and that’s where it should stay”. But it is true. Everyone has a story that can be told, even if they aren’t able to tell it themselves. The problem Hitchens alludes to is making the story interesting enough to make people want to read it, which is the author’s job. For the author the only task in relation to coming up with new book ideas is to keep their eyes and ears open and the story ideas will come. At the moment I’m helping a fellow aspiring author by providing feedback on a book she is writing. I can’t give away the subject as that would be a breach of confidence, but the idea for it is straight off the front pages of the daily newspapers. She was so touched by what she was reading that the idea of not writing a story about it was probably more bizarre than the idea of writing it.  Does that mean that anyone can write a book? Technically yes. If you can write your name you can write a book. However, there is no doubt that some people have an aptitude for it and some don’t. Thanks to the capability to self-publish books that’s available through the digital revolution there are many books that I’ve read in recent years that really shouldn’t have been written, at least not by the people that wrote them. They are living proof of Christopher Hitchens’ corollary. But that doesn’t mean that someone with more aptitude couldn’t write a very good book using the same plot and characters. Do all my ideas become books? Most certainly not. The length of a novel may vary, but generally falls between 80,000 and 120,000 words. I have taken some ideas and barely made it to 10,000 words before I’ve run out of steam. That tells me that, for me, the story just hasn’t got any legs and there’s no point in wasting any more time with it. Of course I don’t delete it. I may have some sudden inspiration that will take it off in a completely new direction, but for the time being it goes into the file marked “not quite as good an idea as I thought”.  As for suggesting your own book ideas to authors, please don’t. It’s not that they aren’t good ideas, it’s that there are legal implications. Most big-name authors will tell you that at some point they have received letters or emails claiming that the idea for a book was stolen because they (the letter writer) once said or wrote down some of the words that are used in the book. The writer of the letter or email then goes on to try to claim money for suggesting the idea or, even worse, for plagiarism. Terry Pratchett’s agent told me that he received an email threatening legal action from someone who had once suggested, in another email, that Terry Pratchett set one of his books in Australia. The threatening email arrived shortly after the publication of The Last Continent in 2008, where Pratchett sets the story in the country of Fourecks on his imaginary Discworld. Fourecks bore a passing resemblance to the country we call Australia. That was enough for the loony who wrote the email. And that’s why authors would prefer it if you didn’t suggest ideas for books. It’s nothing personal. By the way, if that has given you an idea for making some easy money - forget it! Lawyers are expensive, they are happy to take your case because, win or lose, they will still get paid and proving plagiarism is a very difficult thing to do. If you don't believe me, just ask Sami Okri. So I took my idea that I had pitched to Terry Pratchett’s agent and wrote the book myself. It’s called The Inconvenience Store and is available (here comes the plug) on Amazon.  How did I come up with the idea? Easy. I had just been to a convenience store to buy something that they didn’t have on their shelves. When I asked the manager why they didn’t sell it (it was a common enough item) he told me that people often asked for that item, but they didn’t stock it because there was no demand for it. The manager was a totally irony free zone. My response to the manager about his store being more inconvenient than convenient gave me the title for my book and the rest, as they say, is history. So, where is your next book idea coming from? It could be closer than you think. Would you like to be a guest blogger for Selfishgenie Publishing? Just email us and tell us your idea for your blog. The email address can be found on our "Contact" page. If you enjoyed this blog, or found it interesting, be sure not to miss future posts by signing up for our newsletter. We'll even send you a free ebook if you do. Just click the button below.