|

Disclaimer: We are not connected with Bryan Cohen in any way and have no financial interest in his book. This review has not been paid for by Bryan Cohen or anyone else.  This is a review of one of two books by Bryan Cohen that we think should be read in the right order. This first one, “Fiction Blurbs: The Best Page Forward Way” is about improving your blurb writing technique so that readers feel more compelled to buy your book. The second book, “Self-Publishing With Amazon Ads” teaches you about increasing the profitability of your advertising campaigns. What links the two? One of the “tweaks” that the second book suggests to increase sales is to improve your book’s blurb. So, if that is a tip for increasing sales it seems sensible to us to try to improve our blurbs before we started spending money on advertising, so that we don’t spend money on advertising only to find out that our blurbs might need improving.  Still not quite right! Still not quite right! It is putting the metaphorical horse in front of the cart rather than behind it. But don’t worry, we’ll be reviewing “Self-Publishing With Amazon Ads” next week, so that you can get the whole picture. Having said this book is by Bryan Cohen I must now correct myself and tell you that it is actually written by Phoebe J Ravencraft, an associate of Bryan Cohen, who works for his company, Best Page Forward. But they get joint author credits. First of all, what about the authors’ credentials for writing a book such as this? Best Page Forward has written over 5,000 book blurbs for self-published authors. Phoebe herself has written or overseen the writing of around 3,000 of those. She comes from an advertising copywriting background. They have gathered plaudits from satisfied customers and the blurbs they have created have stood the test of time to sell books. I think we can safely say that they know what they are talking about.  In one of our marketing blogs, repeated last autumn, we advised selling the sizzle, not the sausage. In other words, we recommended not trying to describe your book to the reader but trying to excite their imagination about how dramatic/entertaining/insightful/hilarious (insert other adjectives of your choice) your book is going to be. That is exactly what this book strives to do. That was good enough to convince me to buy the book. If it does that for us, the money spent on it will be repaid just by selling two extra copies of one of our books. As both an author and a publisher I have written dozens of book blurbs, so I thought I knew what I was doing. We had done plenty of research to try to find out what made a good blurb and we followed the lessons we had learnt, but there was still a nagging doubt in our minds that we might not be getting it right. Our sales suggested that there was something amiss. We were getting lots of clicks on our adverts, but they weren’t converting into as many sales as they should.  So, when I started to read this book, pennies started to drop to tell me that doing what other people were doing was the problem. What we needed to do was to be different, to make our blurbs stand out from the crowd. Readers are too easily distracted by metaphorical shiny things, so the solution to that is for our book blurbs to be the shiny thing that distracts them from other books. Chapter by chapter, Phoebe (if she’ll permit me the liberty of addressing her by her first name) lays out the elements that go into writing the “killer” book blurb that we wanted, and then how to structure the different elements to get the most out of them. It wasn’t that the blurbs we wrote were actually bad. After all, we're conforming to what we understood to be “best practice”. It was more that they could have been so much better. For the most part, they were selling the sausage, not the sizzle. They described the book, but they didn’t describe the emotional ride that was contained within the book. Emotions, it turns out, are the sizzle that sells the sausage.  I sort of knew that already, because I have always believed that books should be character led, not plot led. Readers engage with the characters at an emotional level and come to care about them and that is what keeps them turning the page, not the plot itself. And that emotional engagement, it turns out, is what has to be at the heart of the book’s blurb. There is a lot more to it than that of course. Conflict, jeopardy, structure and vocabulary all play a massive part, but without the emotion the book still won’t sell. I’m not going to ruin the book’s sales by telling you what tools and techniques are taught within its covers. You’re going to have to pay to find out, just as we did. Suffice to say that every page provides something new to learn. Even if your blurbs are already good I feel quite confident saying that you will learn something new from this book. Readers will note that I have given the book only 4 stars where, from what I have said, you might expect that it should be worth five stars. That isn’t because of the lessons that the book teaches. It is only because of the style in which those lessons are taught. "As an author and as a publisher I have limited time available" The author uses well known books and films to illustrate the lessons and there is nothing wrong with that. Many of those books and films are her personal favourites. Again, there’s nothing wrong with that. However, at times I found that the point being made was laboured and that the author was getting rather carried away with her own passions. While such enthusiasm is to be admired, it can be a little too much when the reader has already grasped the key message and only wants to move on to the next lesson. As an author and as a publisher I have limited time available, and this book took a little more time to read than was essential. Perhaps it was designed to pad the word count, so the reader thinks they’re getting value for money, but the real value isn’t in the number of words, it’s in the messages. But that is a minor criticism and I feel secure in saying that anyone buying this book will have their money repaid quite swiftly if they learn the lessons and apply them to their blurb writing.  So, what are my main takeaways from this book? The first one I sort of already knew but being reminded of it didn’t hurt. The purpose of the blurb is not to describe the book; it is to sell the book, which is an entirely different technique. According to Phoebe, you don’t even have to read the book to be able to write its blurb. Secondly, creating a good blurb isn’t easy and it requires practice and hard work. I soon discovered that when I tried to re-write the blurbs for the books we publish. What I thought would be about ten minutes work per book turned out to take considerably longer and they still aren’t perfect (though they are better). Finally, a good blurb taps into your emotions and raises the “risk” level for the protagonist so high that the reader has no choice but to buy the book to find out what happens. Get that right and the book will sell. But I’m sure you want to know if re-writing the blurbs for our books made any difference to our sales.  First of all, judge for yourself. If you go to our “Books” page we have re-written most of our blurbs. I’m not suggesting they are perfect. In fact, I’m sure that Phoebe J Ravencraft would suggest some improvements if she were to read them. But they are different to our previous style. Just ask yourself one simple question – having read any of those, do you feel tempted to buy the book? More importantly, has our conversion rate for sales improved? We actually got an instant return for one book. The day we changed the blurb it got its first sale in months. Coincidence? Possibly, but we think it may have been the new blurb. Then a second book got its first sale in months, followed by a third. Too many for coincidence; this was a trend. I’m not going to pretend any of those books went from non-seller to best-seller overnight as a result of the tweaks we made - but “Fiction Blurbs: The Best Book Forward Way” paid for itself within a week and is still paying for itself in terms of sales. I highly recommend “Fiction Blurbs The Best Book Forward Way” by Bryan Cohen and Phoebe J Ravencraft. To find out more about the book, click here. Next week we’ll be reviewing another book which could help you to sell a lot more of your own books, so be sure not to miss our blog. In fact, why not sign up to our newsletter to make sure you don’t miss it. We’ll even send you a free ebook if you do. Just click the button below.

0 Comments

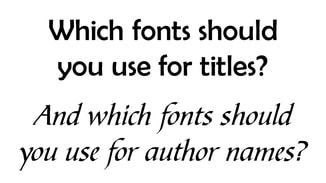

Disclaimer: We are not connected to Book Brush in any way other than as users of the product that has been reviewed. This review has not been paid for by Book Brush or by any other person or organisation.  This article is a review of the Book Brush app which allows authors to design their own book covers, rather than having to pay someone else a lot of money to do that for them. I have to say up front that some of the things that Book Brush allows you to do can be done just as easily in PowerPoint (if you are good at using PowerPoint) but, equally, some of the features are unique. And what is most unique as that it draws together everything you may need to be able to do under one URL. The service is provided on an annual subscription basis, charging at 3 levels: silver, gold and platinum. We paid for the silver level ($99, about £85) as that provided the things we needed right there and then (we knew we could upgrade later if we wanted to). Looking at the other two packages, it is hard to see them offering that much more – but on the other hand if it is something you want to do repetitively and you have no other way of doing it, you may regard the extra money as being well spent. I’ll cover the differences in the subscription levels a little later in this blog. "doing it myself was a no-brainer" The first thing I found useful was the introduction video that showed me how to use the app. I was able to watch it before I had even subscribed, and it persuaded me that what was on offer was going to save me money. Typically, we pay a designer on fiverr.com around $100 to provide us with an ebook and paperback cover package (with us providing the images to be used) and, as publishers, we may need a dozen of those each year, costing around $1,200. So, paying $99 a year and getting one of our team to do it was a no-brainer, providing we can create the sorts of designs that we want. How long does it take to design a cover?  Having watched the video and learnt the basics, and combining it with some use of PowerPoint (I’ll tell you why later) I was able to create a cover for the next Carter’s Commandos book in around 15 minutes. OK, the design isn’t complicated, but using the sorts of templates that are available within Book Brush, it wouldn’t have taken much longer to produce something more elaborate. I was able to do that after watching just one video and spending about an hour playing around with the various features. What’s more, I rather enjoyed doing it because the results are so easy and quick to see and it’s fun to be able to experiment with different designs. Warning to procrastinators: It is very easy to spend a lot of time playing with Book Brush while convincing yourself you are doing something productive. So keep an eye out and don't fall into that trap when you should really be writing. At the end of the process we know that by using Book Brush templates, our finished cover is going to be fully compatible with the technical requirements for KDP and other book publishing sites. But the biggest advantage is the range of templates that are available and how you can manipulate them to create a design that is unique to your book. The templates and other images are conveniently organised into genre specific groups.  KDP cover creator offers you about a dozen templates and they are pretty much fixed. You can add your own images, of course, but trimming them is difficult and it is inevitable that your book cover is going to look like hundreds of others, which is where Book Brush offers one of its great advantages. Not only that, but you have an almost unlimited ability to change colours and fonts. The platinum subscription for Book Brush offers the flexibility to remove backgrounds from images, but you may not want to pay for that. Removing background allows several images to be combined to create unique covers. Which is where PowerPoint comes in. If you know how to do it, you can remove backgrounds from images in PowerPoint, save the combined image as a .jpg and then import it into Book Brush ready to use. I’m not going to go into detail about how to do that in this blog. We searched YouTube and found this “how to” video for people who don’t already know. Along with all the templates Book Brush also has access to hundreds of thousands of free to use images which you can apply to your covers but, of course, you can also create or buy your own. They have a wide range of fonts and all the special affects you would expect to see for applying shadow, changing transparency etc. If you want to use a particular font and it isn't available in Book brush, you can import it.  There are also some blogs on the site that could be helpful to you, such as the one we read to discover what fonts work best for which genres and which should be paired together to differentiate between titles, sub-titles and author names. So, what more do you get if you upgrade? With the gold package you get templates into which you can insert your finished covers in suitable formats to use for your social media marketing, cover reveals etc, such as showing the cover in a Kindle frame with accompanying promotional text. That was about all I saw there that was different and not something that I considered to be worth paying for. With platinum you get the ability to create video trailers for your books, by combining either your own video images or using their collection of stock video. To that you can add music or a narration. The package is quite easy to use, can create videos compatible with the different social media platforms and the results look very professional. But it isn’t something we would use a lot so, in our opinion, it didn’t justify the additional $147 subscription fee.  If they offered the opportunity to buy a one-off video package for $10 - $15, we’d certainly use it, but I don’t think the subscription offers value for money unless you’re going to be creating a lot of video trailers. Where Book Brush really comes into its own is in creating paperback and hardback covers. With the wide range of trim sizes on offer through KDP and the wide variation of page counts between books, coming up with a PowerPoint template that works for every book is impossible, so it’s all down to trial and error, which can take hours of work to get right. But Book Brush just asks you how many pages your book has and then creates a custom template for you which is guaranteed to pass KDP’s quality standards. All you have to do is overlay the different content you want to use for your design and, again, you can use their designs and images or create your own. So, overall we are quite happy with Book Brush. It’s easy and quick to learn and you can start producing professional looking book covers within an hour of paying your subscription. We certainly recommend the silver package. Whether you want to pay more for the extra buzzers and bells is down to you. If you would like to know more about Book Brush, click/tap here. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative, be sure not miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. We’ll even give you a free ebook for doing it. Just click the button below. This week we hand over our blog to one of our authors, Robert Cubitt, who has been dabbling in the world of audiobooks. All views expressed by the blog's author are his own and are not necessarily shared by Selfishgenie Publishing  As an Indie author, have you ever wondered if you should turn your masterpiece into an audiobook? I did wonder, so I did some research to see if it was the right thing for me (spoiler alert – it was). First of all, the market for audiobooks in the UK in 2021 was £151 million, up from £133 million in 2020. In the USA the market was worth $4.2 billion in 2021 and is expected to grow to $33 billion by 2030. Just a microscopic slice of either of those pies is a significant amount of money. So, why are more Indie authors not pursuing this avenue for selling their books?  Aside from snobbery (some authors don’t believe that audiobooks are really books) the answer is cost. First of all, audiobooks cost far more to buy than either an ebook or a paperback. In the US an audiobook will cost between $20 and $30 and prices are comparable in the UK. For this reason, many audiobook retailers work on a subscription basis, allowing listeners to download multiple titles each month for around $15 (and the equivalent in pounds).  If you subscribe to Spotify or iTunes, you will already be familiar with this and Audible provides a typical subscription model for audiobooks. In essence it is no different from what KindleUnlimited does for ebooks. The reason behind this cost is that an audiobook requires a narrator, and they don’t come cheap. If you want a well-known actor to narrate your book you can think of a starting price in excess of £3,000 ($3,500) and some audio books use more than one actor: an overall narrator, a male character lead and a female character lead, which further increases the cost. The cost of those voices has to be recovered before either the author or the publisher makes a penny in profit.  But I wasn’t going to be deterred by this, so I went looking for cheaper options – and found them. I’ll be talking about acx.com a lot, as they are the largest distributor for audiobooks. They sell audiobooks through Audible, Amazon and iTunes, which between them control around 80% of the audiobook market. If your audiobook isn’t on acx.com, it isn’t anywhere. But I’m getting ahead of myself. The first thing you need if you want to publish an audiobook is a narrator. So how do you find one of those? And, more importantly, how do you find one that won’t charge an arm and a leg to work with you?  My starting point is the same as for any job I want doing in relation to publishing: fiverr.com. A search for “audiobook narrators” provided me with an extensive list of potential candidates. Each one has posted an audio clip of their voice, so you know what you are getting before you even approach them. If your book is British based you will want a British accent (unless you are Lee Childs, who sets his books in the USA), likewise if you are an American author you will probably want an American accent. You may want to choose between a male and a female narrator. Whatever you want, you will probably find someone to offer it. There’s even one that offers to read a French translation of your book for the French market.  Rates for narrators vary and they quote their prices by 100, 200, 250 words etc so do check carefully what they are quoting so that you can compare prices properly. The narrator I picked out suggested a starting price of £4.54 (around $5.25 at current exchange rates) for 250 words, which is very much at the economy end of the scale. (I will provide his details at the end of the blog.) But his voice sounded good, so I asked for a “custom quote” based on the length of my book. My narrator came back with a quote of $1,800 (about £1,560).  If that makes your eyes water, then I empathise because it made my eyes water too. However, you must remember that, unlike many services, you aren’t just paying for time, you are also paying for talent. But my books have been doing well recently and paying that amount from my recent royalties wasn’t out of the question. However, I wasn’t going to commit to that amount of money on the spot. I messaged back to the narrator to say I would think about it and get back to him. At which point the negotiations really started. My narrator told me he could do it for about half that amount, but with a royalty share option – 50:50. This is a facility that acx.com operates, so the author doesn’t even have to pay the royalties to the narrator; acx.com does that. If you think that is giving away a lot, please remember that 50% of something is always better than 100% of nothing.  So, we agreed $900, which would be paid through Fiverr.com and the rest would be paid in royalties through acx.com. So, just a quick conversion for my British readers, I paid about £780 upfront to my narrator, plus Fiverr.com’s charges. Please note that the royalties scheme has no limit to it. The author doesn’t stop sharing when a certain level of royalties have been reached. It goes on for as long as the audiobook remains on sale. That can mean my narrator receives a lot more than $1,800 if the book is a good seller, which is why some narrators like this way of doing business. But, if the book isn’t a good seller, my narrator (and me) may not make very much from it. That’s the gamble we are both taking.  Don’t be surprised if your narrator asks about your ebook and paperback sales figures before he or she agrees to a royalty share deal. And they may check out the book’s sales ranking on Amazon, so don’t try to fool them. Having never done this before, I decided to find some resources to tell me how it all works. In terms of the technical requirements for the book, I found this helpful check sheet. It gets a bit technical in parts, but it does provide the basics. Most of that is your narrator’s responsibility, but it does no harm for you to know about it too. I then found this video on YouTube which provides a practical demonstration. That is stuff that you as the author will need to know in order to upload your audiobook for distribution.  In terms of uploading your book, it is no more difficult than using any of the self-publishing websites with which self-published authors, like you, will already be familiar. However, there are two things which are very different:

Because I had already decided on my narrator, I didn’t need to get into the audition process. But basically, if you want to look for narrators who are already registered with acx.com (and the vast majority are) you can upload an extract of your book for prospective narrators to audition and bid for the work. You can apply filters for your narrators, such as nationality, language, gender, accent, and general tone of voice you want for your book (serious, dramatic, humorous etc). If you have already decided on your narrator, as I had, you can search for them by name in the appropriate section, and they will be linked to the project.  When you tell acx.com the wordcount for your book, they do a calculation on how long it should take for a narrator to read (a 90k book is about 9.5 hours). In the appropriate section of the site, you can then enter an hourly rate you are willing to pay. Multiply one by the other and you get an indicative cost for your audiobook. I would suggest a starting price of about $50 (£45) per hour. If you don’t get any bids to narrate your book by the cut-off date that you specify (typically 2 - 5 days) you can increase the hourly rate until you get a bid with which you are satisfied. The site pays royalties of 40% for exclusive distribution rights for your book or 25% for non-exclusive rights. I went for exclusive, which gives me 20% and my narrator 20% Having already chosen my narrator, and found him in acx.com’s directory, I filled in the details for the royalties share scheme. This section also asks if you agree to fund some or all of the narration costs. Don’t tick that box if you have agreed a “royalties only” scheme with your narrator, as I had; acx.com doesn’t need to know about the lump sum payment made using Fiverr.com Caution: once you have posted these details you can’t change them. You have to cancel the whole project and start again (as I discovered).  And that’s about it. Your chosen narrator will get to work and provide you with a 15 minute segment, so that you can verify they are narrating your book the way you expected. Once you have signed off on that they will carry on with the rest of the recording and they upload the files when they have finished. You listen to the files to make sure you are satisfied and after that it is no different from publishing an ebook or paperback. Publishing an audio book isn't a speedy business. Firstly you have to wait while your narrator actually narrates your book and it probably isn't their full time job, so they will be doing it in their spare time. Secondly, once it is uploaded there is a lengthy quality review process which acx.com says takes 10 business days to complete but which took longer in the case of my book, for some unexplained reason. Then comes the hard part, of course – marketing the audiobook. Because, just like any other publishing medium, no-one is going to stumble on your book by accident. You have to tell readers/listeners about it, and where to find it. But this is where you get a little bit of a bonus by being on a royalties share basis. Because your narrator has a vested interest in the book being successful and they will probably do some marketing on their own behalf. Can you narrate your own book?  If you think you have the voice for it, then of course you can. But beware, acx.com has very tight quality standards and you may not be able to reproduce these at home. Readers also want a “clean” listening experience, so they don’t want to hear the sound of your children squabbling in the background, or your dog barking at the neighbour’s cat (or both). See the technical checklist I linked to above. So, how successful has my audiobook been?  I have no idea because it has only just been launched. But I’ll be back after Christmas with an update, so be sure to check back. And if you want to find out more about my audiobook version of Operation Absolom, you can download a free extract here. Or you can check it out on Amazon by clicking here. If you are an author who would like to use a male British narrator for your book, then I am pleased to recommend Michael Hajiantonis. You can find him on acx.com under that name or you can do what I did and find him on Fiverr.com using this link. If you would like to get a promo code for a free download of the Operation Absolom audiobook, just email us through our contact address. All we ask in return is for a review and a share on your social media. Good luck! If you have enjoyed this blog and want to make sure you don’t miss future editions, you can sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so. Just click the button below. Disclaimer: This blog talks a lot about Amazon, but we are not connected to them in any way other than they sell our books. We are definitely not being paid to mention their name and we are not recommending Amazon. We are just recounting our experiences in the hope of passing on some of the knowledge we have gained.  As an author who sells through Amazon, you will know all about “sales ranking”. If your book sells, the ranking improves and people are encouraged to buy your book because other people have bought it. And if your ranking is low, people think your book isn’t any good because other people aren’t buying it - but that is flawed logic. Just because a book isn’t selling it doesn’t mean it isn’t any good. It may just mean that nobody knows about it (we blogged about advertising last week, so we’re not going to go back over old ground). But you won’t convince some readers that a book is good if it isn’t selling and there’s not much we can do to change that mindset.  We have been fortunate over recent weeks that several of our books have sold well and their sales rankings have improved exponentially. Instead of being in the 7 digit ranking range they are into the lower end of the 5 digit range – and are still climbing. That’s for their overall, ranking of course, not the category ranking. In some obscure categories its possible to be the No 1 bestseller just by selling a single copy. So that isn’t a good comparison for the purposes of this blog. But we believe our books’ rankings should be higher still and we also believe that the way Amazon calculates their rankings doesn’t take into account a whole raft of “sales” through their own platform. I’m referring to Kindle Unlimited (KU) pages read. While they may not be direct sales, the way that a book is sold, the reader is still paying to read the book through their KU subscription and the author is still getting an income from those page reads. So, it is our contention that those page reads should be included in the calculations of sales rankings, which are an indication of the popularity of the book. KU page reads account for about two thirds of all our sales income (more for some individual titles). It is the equivalent of a lot of books sold. But Amazon doesn’t count them and there is no valid reason, as far as we can see, why they shouldn’t. In fact, it might actually be to Amazon’s benefit to include KU pages read, because the more popular a book, the more copies it sells and the more money Amazon will make from those sales. They are, effectively, depriving themselves of potential income with their current policy. I’ll use just one of our titles as an example of what we mean. "Our guestimate is that it would put the book into the top 1,000" But before we go on, a quick bit of jargon busting, for those of you who might need it. KENP means Kindle Edition Normalised Pages. It is the number of pages that Kindle Direct Publishing uses to calculate an author’s royalties for KU downloads. The more pages read in a book, the more the author gets paid. It is used to factor in the different font sizes and line spacings that authors use, which makes direct comparisons between the number of pages in a book problematic. We’re not sure how the KENP for a book is arrived at, but we suspect it may be based on character or word counts Mansplanation over, back to the blog.  Operation Absolom is the first book in Robert Cubitt’s “Carter’s Commandos” series. In July 2022 it sold 11 copies. This elevated it to around 30,000 in the Amazon rankings at the time. Although Operation Absolom is 296 pages long in paperback, its KENP is 437 pages. During July 2022, 19,215 KENP pages were read using KU. Divide 19,215 by 437 and it works out at 34 complete books. So, if 11 books sold gives Operation Absolom an average sales ranking of about 30,000, what would another 17 books give it if they were included in the figures? (BTW it actually peaked at around 10,000 - 7/7/22) Our guestimate is that it would easily put the book into the top 1,000, which makes the book look very popular indeed – as it is in reality. OK, we’re not talking J K Rowling or Lee Childs popular, but it is a lot more popular than a million other books on Amazon. "Perhaps weight of numbers might encourage a shift in policy" We could quote similar figures for the rest of the Carter’s Commandos series, because once people have read the first book it is clear they are then reading the rest of the series. But you get the idea from the one title we have used as an illustration. But it doesn’t look like that on Amazon. So, what can we do about it? We have already emailed Amazon to ask them why they won’t change the way they calculate their sales rankings. After all, they have all the data to hand and doing a new calculation that includes KENP would hardly be rocket science. This was their reply: “Sales rank is determined by a number of different inputs and may change over time. Amazon is constantly working to improve the quality of information available to our readers and authors. Please note that Sales Rank fluctuates every hour in line with customer demand and in relation to the demand for other books, both of which may vary based on factors such as popularity of new releases, seasonality, etc. Rankings reflect recent and historical activity, with recent activity weighted more heavily. Rankings are relative, so your sales rank can change even when your book's level of activity stays the same. For example, even if your book's level of activity stays the same, your rank may improve if other books see a decrease in activity, or your rank may drop if other books see an increase in activity. When we calculate Best Sellers Rank, we consider the entire history of a book's activity. Monitoring your book's Amazon sales rank may be helpful in gaining general insight into the effectiveness of your marketing campaigns and other initiatives to drive book activity, but it is not an accurate way to track your book's activity or compare its activity in relation to books in other categories. Thanks for taking time to share your thoughts about considering KENPC in sales ranking calculation. Customer feedback like yours is very important to helping us continue to improve our products and services. I appreciate your thoughts and will be sure to pass your suggestion along. Please refer to our Sales Ranking Help page for information regarding Sales Rank - https://kdp.amazon.com/help?topicId=A21KM4BNAD42EJ”  Amazon sales data - just the tip of the iceberg. Amazon sales data - just the tip of the iceberg. We emailed back to them, saying that they were undermining their own reply. If tracking the effectiveness of marketing is an important use of sale rankings, then Amazon should surely be doing its best to maximise its utility by including KENP data, because that fluctuates in response to marketing activity as well I also pointed out that by not including KENP, they were showing customers the tip of the iceberg, not the whole iceberg. They did reply once more, but only to provide platitudes. But if you are an author and your books are read using KU, then this is something that you should be concerned about as well. So why don’t you add your voice to ours and ask the same question? Perhaps weight of numbers might encourage a shift in policy Let’s face it, you have nothing to lose and your book’s sales ranking have everything to gain. But while we are on the subject of KU, would you like to help other Indie authors to maximise their income? I hope you said “yes” because it only takes a few seconds and will cost you nothing. When you get to the words “The End” in a book, there are often a few more pages left in it after that. They may be a preview of another book or an advert for other titles. It doesn’t matter. Just keep on swiping until you get to the actual end, so that the author gets paid for every last one of those KENPs. It may only be a few pennies (or cents) extra, but they add up. Even if the book wasn’t to your taste and you didn’t finish it, which is hardly the author’s fault, you can make sure they get full recompense for their work by swiping through to the end anyway. As I said, it costs you nothing but a few moments of your time. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative (both we hope), be sure not to miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. We'll even send you a FREE ebook for doing so. Just click the button below. Disclaimer: This blog talks a lot about Amazon, but we are not connected to them in any way other than that we use their platform sell our books. We are definitely not being paid to mention their name and nor are we recommending their services. We are just recounting our experiences in the hope of passing on some of the knowledge we have gained. Here at Selfishgenie Publishing we know that it pays for small publishers and Indie authors to advertise. Not only do we know this, but we have the data to support our arguments. What we have also found, however, is that we can’t rely on some of the data that is provided to tell us if our advertisements are paying for themselves. Over the past 6 months we have been experimenting with our advertising tactics to see which give us the best results. Recently we have been focused on Amazon as the advertising platform of choice. But the first thing we noticed was that the metrics (measurements) provided by Amazon on their platform weren’t matching up with our actual sales.  According to the report for one campaign, we sold x number of books, but according to our actual sales data we had sold yx copies, which was a considerably larger number (sorry to be so vague with the numbers, but that data is privileged information). This is an important difference, because had we believed Amazon’s numbers, we would have concluded that our advertising budget had been wasted. That is because of the ACOS. For those of you unfamiliar with ACOS, it is a calculation that Amazon does to compare the cost of the advert with the income Amazon believes the advert generated It means “advertising cost of sales”. Based on their figures, our ACOS was 198% of what we would get back in royalties as a result of placing the advert. In other words, if we had spent £2 on advertising we would only be getting back about £1 in royalties.  .And that does make it look like we had wasted our money. However, a quick click over to the various websites where we sell our books revealed that we had sold far more books than Amazon knew about – and that included sales through Amazon itself (BTW, when we say “sales” we also include Kindle Unlimited pages read. They account for about two thirds of our total revenue). When we divided the ACOS by the revenue that was actually generated, we got a far lower number, which demonstrated that our advertising campaign was justified in terms of its cost. In fact, for every £1 we spent we got over £5 back. Even after splitting that 50:50 with the author, everyone was making money. OK, Amazon doesn’t know how many books we have sold through other websites and we don’t know how many people have seen our books promoted on Amazon and then gone elsewhere to actually buy them. “Ah,” you might say, “so how do you know those sales were the result of your advertisement?” A fair question. So, why the discrepancy in data? The answer is that we know because the sales were for the same books as we had advertised, or they are part of the same series and there had been a sharp “up tick” in sales coincidental to the dates when the advertising campaign had been run. So, why the discrepancy in data? The first reason is that Amazon does its calculations based on “impressions” and “clicks”. First of all, Amazon Ads measures how many customers had the advertisement placed in front of them (the basis of their charging), either as a result of a search or as a “recommendation”. Then they measure how many of those customers clicked on the link in the advert to take a closer look at the book, and then they count the number of clicks that were made to actually buy (or download) the book. The first number was very high, the second number was lower and the final number was, unsurprisingly, lower still. But what Amazon doesn’t take into account is the psychological effect of the advertising process.  Oh, here we go, he’s wandering off into some metaphysical introspection now. No – I’m not. Please bear with me. Firstly, there is an old adage in advertising that says people have to see an advertisement 7 times before they respond to it. As with all such rules, it is a generalisation. Some people will respond the first time they see an advert, because they have a need for the product and now they now know how they can satisfy that need. Some people, on the other hand, may never respond because they have no need for that product, or because they are very happy with a similar product supplied by a competitor.  But this generalisation around ad campaigns is important, because the author has to to allow time for those 7 exposures to the ad to take place. In all our ads we have noticed that response was lowest at the beginning of the campaign and then increased as time went on, usually from around day 4, until it reached a plateau. We also noticed that sales were highest at the weekend (including Friday evenings), which suggests people buy more books then. So, it seems to be a good idea to time the ad so some of the exposures occur towards the end of the week, for maximum impact. A second reason is that the advert is for a product the reader may have already purchased, but the target is reminded that the same supplier has other products and they go and look at those instead. Eg they see an advert for Heinz tomato ketchup, they already have enough ketchup, but it reminds them they need Heinz baked beans and they go and buy those instead. We know absolutely this was what was happening with our books. We were making sales of titles other than those we were advertising. People had already bought Book 1 in our Carter’s Commando series, the book we were advertising, but they were reminded of the author’s name and went looking for other work by him and bought those books instead. The final part of the conundrum is that sales continued after the advertising campaign had ended. Why was that?  Partly the same as the reason above, the readers went and looked for other titles by the same author after having bought the one we advertised. But part of it was that either the author’s name or the book’s title had been subconsciously planted in the reader’s memory, so that when they saw it pop up in search results later in the month (which we hadn’t paid for) they responded and bought the book. So, what did we learn by running these recent advertising campaigns:

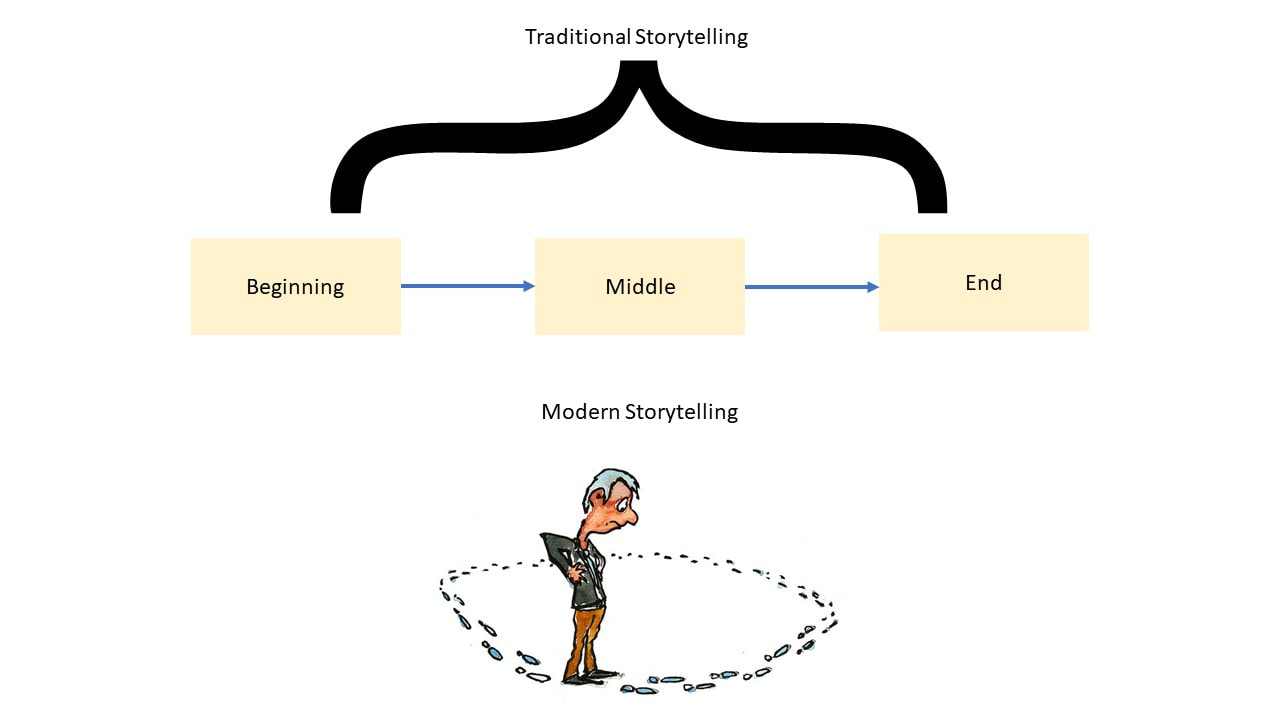

Here endeth the lesson, Go in peace to enjoy the rest of your day. But if you are struggling to make sales, you may need to think about paying for some advertising. We know it costs money, but if your book sells, it will be a worthwhile investment. And if your book still doesn’t sell, you have to ask yourself why readers aren’t responding to it. But that is a whole different blog. If you have enjoyed this blog or found it informative (Hopefully both), be sure not to miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. We'll even send you a FREE ebook for doing so. Just click the button below. Once again we turn our blog page over to a guest blogger. The views expressed are those of the blog's author and don't necessarily represent the views of Selfishgenie Publishing  Have you noticed how books are all starting to conform to a pattern these days? After reading the start of a few books quite recently I rejected them, but it was only after I rejected them that I started to realise that the reason I rejected them was because they weren’t conforming to the pattern. Therefore, I wasn’t prepared to carry on reading them. Which was most unfair on the authors who had invested so much time in writing them. So, what is the pattern? It’s the habit many authors now have of hitting the reader between the eyes on page one of the book, with some sort of action scene, before dialling down the action to properly introduce the characters and develop the plot. They then pick up where the action left off and continue the story in a more linear fashion. I have to plead guilty with regards to my own books. It doesn’t just apply to books that are action focused. Romances, too, sometimes start in the middle before returning to the beginning. So, has this always been the way books were written? Going back deep into history, to the start of my own reading, I remember that stories happened in a predictable order. There was the beginning, where the characters were introduced and the starting point of the story was established, then a middle, where the plot was developed, then an end, where the climax was reached and everyone lived happily ever after. This allowed the author to develop their characters before launching them into their adventures. Who could imagine “Pride and Prejudice” being a success if we didn’t know all about Elizabeth Bennet’s personality from the very start.  If you think about the fairy stories of childhood, they always conformed to the beginning, middle and end pattern. We don’t first encounter Snow White breaking into the Seven Dwarves’ house, then go back to find out that she was sent out with the huntsman to be murdered on the orders of her wicked stepmother. Similarly, we don’t first encounter Cinderella running away from the ball, losing her glass slipper on the way, then go back to the kitchen to find out she is being bullied by her wicked stepmother and the ugly sisters.. Of course, those stories are for children and a child’s unsophisticated mind couldn’t follow a story told any other way. But what we learn as children tends to stay with us for life. As we grow up the stories still follow the beginning, middle and end paradigm until we reach adulthood. Then mayhem ensues.  The problem with this traditional style of storytelling, of course, is that it takes time to introduce characters, explain who they are and what they are doing. I remember having been bored silly by “The Warden”, a novel by Anthony Trollope and considered to be a classic. The reason I was trying to read it was because it was a set book for my English exams and I was supposed to be learning how to use language and how to tell a story properly. Today Trollope’s book might never find a publisher, because it takes so long to get going (no great loss if you ask me). The same could be said of many other books that are regarded as classics. So why this change in the approach to storytelling? Well, literary agents are partly to blame (or are they?). When an author wishes to submit a book to an agent in order to try to get a publishing deal, the first thing they do is go onto the agent’s website and read the submission guidelines. These are invariably the same. Submit no more than the first 10,000 words or the first 3 chapters. If the agent likes what they read, they will ask for more. If not, they won’t. Even when it comes to publishers who accept submissions direct from authors, the word limit is usually still applied.  So that’s it guys and gals. If you can’t grab the agent’s attention in those 10,000 or so words your book will be rejected. So, in order to deal with that the author tries to inject some action into the first thousand words in the hope that the agent reads on. The result is that the middle of the book, or at least part of it, gets stuck in before the beginning. However, is it really the agent’s fault? After all, isn’t the author making a rather large assumption about what the agent wants to read and is tailoring their book on the basis of that assumption. Maybe the agent actually wants to see how the characters are developed and how the plot unfolds. Maybe that is why so many authors receive rejection letters. Maybe we are making our submissions based on false assumptions. If you are an agent or publisher reading this, perhaps you’d like to comment.  Then there is Amazon. Their “look inside” feature gives the purchaser the opportunity to read a couple of thousand words of a book before they purchase it. This is to match the experience of the “browser”; the reader in the bookshop or library who has the time to spare to actually read the first few pages of the book before they decide whether or not to borrow or buy it. So, again, the author may set out to grab the reader’s attention so that they don’t put the book back down again. But again are we, the authors, usurping the process by making the assumption that the reader won’t borrow or buy our book if we don’t hit them between the eyes on the very first page. It is said that the first line of a book must be an attention grabber. That’s fair enough, but that doesn’t mean that the author then has to launch into climactic action before the reader even knows who the characters are.  As part of the research for this blog (yes, I do research) I read the ‘look inside’ portion of Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick”. This, of course, is reckoned to be another classic. But based on what I read, I wouldn’t buy it. To be sure, Melville’s use of language is beautiful, but in the opening pages of the book not a lot happens. The reader isn’t even told that a whale is involved. We don't even find out who Ishmael is or what he has to do with the story (not a lot, as it turns out). So, is it therefore not the reader’s fault that the whole nature of storytelling has changed? We expect instant gratification. We want the action to start on Page One, and if it doesn’t we put the book down and move on.  Thinking about this made me think about films (movies) and the way they now tell their stories. We are used to James Bond films, for example, where Bond is always in mortal combat with an enemy in the opening scenes of the film, well before the title music starts up. Other films also use this technique. So, maybe, in our minds, we have started to think that is how our stories should be told. We, too, are putting the action in before the metaphorical title music. So, when an author goes back to the traditional beginning, middle and end format for writing, we think it a little bit odd. Is this what guided my decisions to reject certain books? Or is it just me? I may have been rejecting masterpieces, simply because I didn’t have the patience to let the author tell the story properly. I have had the same conversation with my wife when new TV dramas start up. It’s a bit boring, she’ll say, and my reply will be that we have to establish who everyone is first and how they connect together.  Again, thinking of TV crime shows in particular, they often open up with a dead body and it takes the rest of the story to find out who the dead person really was, and all their little quirks and foibles which led them to being bumped off. Along the way we also find out about the police officers who are investigating the death, but not until after the body is found. Would I still watch the programme if it unfolded any other way? I can hardly complain that a character is underdeveloped if I won’t give the author time to develop him or her. I can’t complain about the plot being difficult to follow if I don’t give the author time to explain what is happening. This is particularly so when it comes to back story. It is like trying to tell the story of World War II without first telling the reader who the Nazis were. Will I be changing the way I write my own stories as a result of what I have deduced? I don’t know. I rather like hitting the reader between the eyes on Page One. I don’t do it in every book I have written, but I have to admit to doing it in the majority of them. Judge for yourselves whether it is the right technique. Just click on the “books” tab at the top of this page to find out more. If you enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, be sure not miss future editions by signing up for our newsletter. Just click on the button below. We'll even let you choose a FREE ebook for doing it. Do you fancy being a guest blogger for Selfishgenie Publishing? Just email us and tell us what you would like to blog about. Find our email address on our "Contact" page.

Once again we are turning our blog page over to a guest blogger. All the views expressed in this blog are those of the blogger and are not necessarily representative of the views of Selfishgenie Publishing.  Why do it? Why put yourself through all the trials and tribulations of writing a novel, searching for an agent, then possibly having to do all the work to self-publish if you can’t attract an agent? I have applied some thought to this and have come up with the following list of reasons. It isn’t exhaustive, so please feel free to add your own suggestions in the comments below the blog. 1. You like writing. I know that this sounds obvious, but I have actually met authors who have told me that they love being an author but hate all the writing that goes with it. Sorry, that will never work out. You can test yourself on this. If, suddenly, an hour of your time were to come free, which would you rather do (A) watch something on TV or (B) sit down and try to write something. If the answer isn’t (B) then you are never going to be an author.  2. You have a genuine talent. When you first decide to write you may not know if you have the talent for it or not. Even when you have written your first book and shown it to friends and family you still can’t be sure, because friends and family often want to be kind and so they say kind things about your work. But if you do have a talent then it is vital to express it, or frustration is the only possible outcome. The first review on Amazon (other book selling sites are available) that is submitted by a stranger will tell you if you have a talent or not. But there are two different forms of talent that make a good author. The first is a talent for story telling – and it doesn’t have to manifest itself in the written form. If you are the sort of person who is able to make up stories for the entertainment of others, you have this talent and you are halfway to becoming a successful author. The second talent is the actual writing part. Being able to construct sentences that grab the reader’s attention and provide them with the emotional input they crave. Being literate in the grammatical sense helps, but that can be sorted out by a proof reader or editor. 3. You love reading. Reading and writing go hand in hand. All real authors start off as avid readers. The best books inspire us to have a go, while the worst books inspire us to try to do better ourselves.  4. You live somewhere where there are harsh winters. I’m serious. It’s far easier to sit indoors and write a thousand words if the sun isn’t shining outside. Even small outdoor distractions, such as tidying the garden, get in the way of writing. If you live in the sort of latitudes where it is dark for 18 hours out of 24 (or even longer) then so much the better. 5. You have something you want to say. We all have opinions, but some have stronger feelings about things than others. Writing them down in the form of a novel allows you to imbue your character with your opinions while also telling a story. However, there is a downside to this. You may be alienating all those potential readers who disagree with your opinions. While you may believe that you are right, they have the right to disagree with you.  6. You want to expose something that needs exposing. Making an issue part of your plot allows you to expose a problem or a scandal. If your readers are intelligent (they probably are, otherwise they wouldn’t be reading books, they’d be playing computer games) they will see where the fiction ends and where the reality starts. You can often reach a far larger audience with a novel than with a polemic. To Kill A Mockingbird did far more to expose racism in the USA than any number of learned treatises. 7. You want to entertain people. We can’t all sing or dance or play the piano, but if you can write a decent story, you can be an entertainer. Story telling as a form of entertainment goes back far further in history than music or dance. 8. You have to get the stories out of your head. So many good ideas for stories, but they are no good stuck inside your head. They just nag and nag at you. So, tell the stories and stop them nagging you.  9. It’s cathartic. Expressing yourself artistically (yes, that’s what authors are doing) makes you feel better. Getting your demons out of your head and onto the paper prevents them from praying on your mind and threatening your sanity. 10. You like telling lies. Authors tell lies for a living. The best of them are able to make you believe their lies so well that they can transport you to a whole world that they have created out of their lies. Tolkein, Pratchett, Douglas Adam, Richard Adams, the list goes on but the one thing these greats have in common is that their worlds didn’t exist, but they made us believe in them anyway. They could sell snow to an Eskimo. And One Reason Why You Shouldn’t Become An Author.  1. You want to make lots of money. Sadly, you probably won’t. Even if you sell quite a lot of copies, your publisher, agent, printer, retail outlet etc will all take a cut. Typically the author only gets about 10% of the gross income from sales and then the Inland Revenue want a cut of that. For a £9.99 paperback ($11.50 approx) the author won’t get much more than 80 pence. To make the top 100 best seller lists you have to sell at least 100,000 copies, which means the author might get £80,000 before tax. But the majority of authors, probably 90% of them, will never sell more than 1,000 copes, so earnings expectations are very low. According to The Guardian most authors make less than £600 a year. Given that you have probably invested about 1,000 hours in writing your book, that isn’t a very good return. It’s certainly below the hourly rate for the so-called Living Wage. A meagre 1.7% of traditionally published authors and 0.7% of self-published authors make in excess of £70,000 ($100,000 approx). The article is a bit old now, but the fundamentals of publishing haven’t changed since it was written. The big money from books comes from film and TV rights. If your book attracts that attention then the sky is the limit, but again, that won’t happen for about 90% of authors.  How many authors are out there writing away and how many of them will hit the big time? Well, accurate figures aren’t available because most data is based on sales and if no sales are forthcoming you won’t be counted. Then there are the thousands of authors who are still working away in the bedrooms, kitchens or sheds to complete their first manuscript and can’t be counted because they haven’t yet broken cover. But put it this way, over a million books are uploaded onto Amazon each year, the vast majority by by self-published authors and then you have to add on those that are published by small, on-line publishers. Whereas the total output of the big publishing houses, who dominate the market, is between 1,000 and 2,000 books per year of all types (UK figures). Even with the backing and marketing budget of a major publishing house most of those books will sell less than the magic 100,000 copies needed to make it onto a best seller list. In Susanne Collins’s The Hunger Games the supporters always say to the combatants, “may the odds always be in your favour”. The truth is that in book publishing, the odds are always stacked against success.  Ignore all those claims made by some authors of being “Number 1” on Amazon’s best seller list for such-and-such a category. The way Amazon works you can make it to number one with the sale of half a dozen copies in a day, even less in some obscure categories. You’ll only be there for a day, perhaps even for an hour, but that’s long enough to do a “screen save” to share on Facebook or Twitter. if you doubt me, re-read Reason 10 above. Many writers will never make anything from the sale of their books. That doesn’t mean that they are bad books. How would anyone know if they haven’t read a copy? No, the authors don’t make any money because readers like to stick with the tried and tested. They may read a book that is recommended to them by a friend or relative, but they don’t often go seeking out new authors for themselves. The friend or relative probably bought their copy because it was reviewed in a newspaper or magazine, channels that are securely stitched up by the big publishers. Hey – who said that the world was fair? Show me the contract! That is why authors are always asking for reviews. So if you, as a reader, do find a new author and, if you like their book, please consider sharing your discovery by writing a review. So, if you are going to become an author, do it for the love of writing because it is probably the only reward you will ever get. And for those very few of you who will one day hit the big time – don’t forget the little people! If you have enjoyed this blog and you want to be sure of not missing the next one, just sign up for our newsletter. We promise not to spam you and we'll even let you choose a free ebook for doing it. Just click on the button below. And if you would like to be a guest blogger for us, just send us your blog idea. You can find our email address here.