|

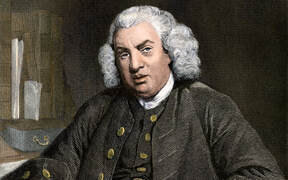

This week our guest blogger takes a look at the vagaries of the English Language and how we ended up where we are. The views expressed in this blog are those of the blogger and don't necessarily represent the views of Selfishgenie Publishing.  One of my friends on Facebook, an Irish lady, posted this picture and asked an open question about who felt confident about the pronunciation of the product name (no, not Heinz - the other bit) . She was re-posting it from another Facebook page which is owned by an American on-line magazine. I was able to reply with the information that English place names that include the letters “cester” don’t actually pronounce the “ces” part, so the correct pronunciation is Wooster-sheer. The incorporation of “cester” into a place name means that it was founded by the Romans when they were in Britain and has its origins in “castra”, which is Latin for a camp. It is also the origin for place names that include “chester” as in Chester and Manchester. From that word we also get Doncaster and Lancaster. Incidentally, the “lan” part of Lancaster comes from the nearby River Lune (pronounced loon), but I’m guessing the people of the city didn’t fancy being known as the people from Looncaster.*  Chester - a city founded by the Romans Chester - a city founded by the Romans The pronunciation of Worcestershire is problematical for three reasons. Firstly, there is the pronunciation of Worc, It looks as though it should be pronounced as work, but the c in cester is soft, which makes the pronunciation worse, both literally and figuratively. I’m guessing the people of Worcester and its parent county didn’t fancy living in worse-tur, so the pronunciation shifted to woos. Secondly the “shire” part is pronounced sheer when it is quite clearly spelt to rhyme with hire. But that’s the English language for you, full of anomalies such as that one. I’ll return to that a little later. The final reason for this pronunciation being problematical, and pedants will already be penning their e-mails to tell me so, is that it is a sweeping generalisation and can’t be universally applied. What about “Cirencester”? They will ask. The “cester” in that is pronounced, otherwise it would be siren-stir and not siren-sester, like sister but spelt with an e. But anyway, Gloucestershire is pronounced gloss–tur-sheer, Leicestershire is less-tur-sheer, Towcester is toaster and Alcester is all-stir.  This is part of the problem with English. It isn’t consistent with the application of its own rules. Especially the English that is spoken in the United Kingdom. Take “I before e except after c”. I think there is sufficient evidence to allow us to draw a veil over that one. In fact, there are far more words that don’t obey the rule than there are words that do. The saying itself isn’t even complete. Ebenezer Cobham Brewer’s 1880 “Rules for English Spelling” gives it as “i before e, except after c, or when sounded as "a," as in neighbour and weigh.” But there is insufficient evidence to support that, either. Despite Cobham being English and never having visited America, the use of his rule in schools started in America, not Britain. But there you go, rules are meant to be broken (actually they aren’t, but that’s a whole different blog). But there are a lot of words we don’t know how to pronounce, or which some Smart Alec decides we are pronouncing wrongly and who change it. Take the name of the warrior queen Boadicea, for example.  Actor Alex Kinston as Boadicea Actor Alex Kinston as Boadicea A long time ago, when I was growing up, she was universally referred to as Boadicea (Boa – d - seer). It is even engraved on her statue, which stands close to Westminster Bridge in London. In 1797 a British frigate was named HMS Boadicea, there was a passenger ship of the same name which was wrecked off the coast of Ireland in 1816 and there was a 1928 film entitled Boadicea. Yet somehow it was decided by someone that this was wrong and all of a sudden everyone started calling her Boudicca (Boo-dick-uh). Why and on what authority? I blame actor Alex Kingston, who starred in the TV drama Boudicca, Warrior Queen, in 2003.  Roman historian Tacitus; AD56 to AD 120 Roman historian Tacitus; AD56 to AD 120 The only reason we know of this woman’s existence (that’s Boadicea, not Alex Kingston) is because of the Roman historian Tacitus, who recorded much of Rome’s history of the first century AD. However, he wasn’t born until AD 56 and never set foot in Britain. Given that Boadicea (I shall insist on using that name) died in AD 61, Tacitus would only have been 6 or 7 years old and could only have heard of the warrior queen second hand from his father, who had served in Britain 3 times, including during the rebellion for which she is famous. He would have heard about her in Latin, the Roman language and not the language of Britain, whose native people were Celts. It is from Tacitus that we get the spelling and pronunciation of Boadicea, not Boudicca. As the Celts didn’t have a written language at this time, we have no idea how her name would have been spelt or how the Celts would have pronounced it. So, it would appear, someone has taken it upon himself (or herself) to decide how the Celts would have pronounced it, with no regard for the lack of historical fact. They may look to Welsh, Scottish or Irish pronunciations, but that would be wrong, because those nations would have rendered the name into their languages from Latin as it was the only written source available.  If you doubt this, then you have only to look at how Welsh and Gaelic speakers render modern words into their own language. The Welsh for “television” is teledu and the Irish is teilifís. Given that these words were created in modern times they could just have been accepted without translation, much as the French use l’weekend, but no, they had to be given a linguistic twist to make them “Celtic”. Could the same not have been done with the name of Boadicea? Is the use of the name Boudicca not just us pandering to first century Celtic chauvinism? Or maybe even to late 20th century Celtic chauvinism. What is my evidence for all that? She wasn’t actually a Queen at all so would not have been known widely outside of her own lands. She was the wife, and subsequently widow, of Prasutagus who was a client King of the Romans in an obscure and quite remote part of eastern England, a small part of the county we now call Norfolk. Her rebellion was short lived, lasting only a few weeks, and while she wrought havoc during that time she died ingloriously, crushed by the Roman legions. She wouldn’t have been admired, even by her own people, after that defeat. In fact, given the reprisals visited on the natives by the Romans after the rebellion, it is more likely that her name would have been more cursed than celebrated. As I said, the only reason we know about her at all is because of a Roman historian who wrote her name in Latin and it was Boadicea.  But back to words and their pronunciation. How do you pronounce “bow”? If you have thought about it you will have come up with two different pronunciations. Pronunciation (1) rhymes with “go” and pronunciation (2) rhymes with “cow”. You only know which is correct when you put other words alongside it to make it clear which bow you are talking about. So, you would need to know that the mother tied the ribbon into a pretty bow for her daughter’s hair, or that the man bent over in a deep bow of respect for the king. English is almost unique in having words that can be both nouns and verbs, depending on how we use them. No other language does that. This is why we get a noun such as bow, which can mean a knot or a weapon, and also a verb, to bow. We also have run, which is a verb and also a noun – a place for running as in chicken run and walk, a verb which means to move at a particular pace but which can also be a noun – a good walk. There are many others. How do we teach this to our children? Actually we don’t. They appear to learn it for themselves. No one is sure how, but they seem to pick it up instinctively. However, in many ways English is also a simple language. Take the definite article “the” as in the chair, the table etc. That’s it. That’s all we have. It’s gender neutral and doesn’t change between the subject and object of a sentence. German has der, die, das, den and dem for the same thing and the French have le, la and les and also, frequently, l’. In German there are 7 different versions of “you” depending on gender and familiarity with the person being addressed. The French have at least 2, tu and vous (I’m not a linguist so I am happy to be corrected on that). The Japanese have 7 forms of “thank you” starting with the simple arigato and moving up though levels of formality until the speaker is lying prostrate, face down on the ground. Just joking, but it isn’t far from the truth. The Japanese language is very big on formality, as are many others. English, however, seems to be much less worried about formality these days.  Much of this is because our language isn’t pure. 2,000 years ago the residents of these islands would all have spoken the Celtic language(s), because the Romans’ only successful invasion wasn’t until AD42 (get ready for a big anniversary party in 20 years’ time). But they wouldn’t all have spoken in the same dialect. We know this because Welsh, one of the ancient Celtic languages, is different from Gaelic, which is spoken in both Scotland and Ireland but has differences even between them. They are all different from Manx, spoken on the Isle of Man., Then there’s Cornish and Breton. It wasn’t really the Romans that brought us Latin, it was more to do with the clergy, who used Latin to communicate between themselves and taught it to the children of the aristocracy and the wealthy, who also used it as a way of communicating with their peers throughout Europe. Many of our words have a Latin origin, even though a lot of them came via other European languages. European philosophers loved the Ancient Greeks and quite a lot of our words have their language as their origin because of that, especially those relating to medicine and science.  About 1,500 years ago our ancestors started to speak Anglo-Saxon, brought with us (or perhaps to us, depending on your ancestry) by the invaders who filled the power vacuum created when the Romans went home. This is still the basis for our language but only scholars of mediaeval languages would be able to understand what a Saxon warrior was saying, were one to rise from the dead in today’s Britain. Mixed in with our Anglo-Saxon is Norse, brought to us by the Danes and Norwegians between 1,300 to 1,000 years ago, then sprinkle in some Norman French which arrived 950 years ago. Thanks to the Plantagenet’s we get more French, the real thing, which was brought in about 850 years ago and from that recipe the language we now call English began to emerge about 700 years ago. English wasn’t even the official language of the Royal Court until the time of Richard II, who died in 1400 (Trivia - he also introduced the fork into England as an implement of cutlery). With a bit of difficulty, we would be able to understand the dying words of Watt Tyler, the leader of the Peasants’ Revolt, who died in 1381. As he was beheaded his last word was probably “argh”, but you get the idea.  The eastern influence The eastern influence Even though English was a fully formed language by the 1500s, it didn’t stop changing even after that. In the 19th century we started to adopt words from much further east. If you are in the habit of wearing pyjamas when you are in your bungalow, you are using two words that have their roots in India. From that it is unsurprising that so much of our language is confusing. Each new addition brought new words, new ways of saying things and new ways of spelling, much of which wasn’t written down because the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes didn’t have a written language at the time of their arrival. It was monks who wrote things down and they did it in Latin, not Anglo-Saxon. When the monks started to create a written version of the common languages they had to invent new letters, such as æ because there was no equivalent sound in Latin. They even had to invent the letters J and W because these weren’t in the original Latin alphabet. That’s right; You couldn’t go to a J D Wetherspoon’s pub in early Anglo Saxon times, it would have been I D Utherspoon’s.  The grumpy looking Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) The grumpy looking Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) In fact English spelling as we know it didn’t come in until Samuel Johnson published the first English dictionary in 1755. Up until then people spelt things pretty much as they felt like it; even their own names. There are, allegedly, at least three different versions of the spelling of Shakespeare’s name, all in his own handwriting (scholars now dispute this, but they always did like to spoil a good story). Even after the publication of Johnson’s dictionary it took some time for spelling to become standardised and to take on their modern forms. American spelling didn’t start to be standardised until 1828 when Noah Webster published his “American Dictionary of the English Language”. This is the one that led to the Americans starting to leave the u out of words like colour and to put z where it had always been perfectly adequate for an s to be. Webster felt it necessary to try to simplify the language for the benefit of the wide variety of immigrants who were arriving in their droves from Europe.  Just a note for my American readers (and many British too, because they make the same mistake). When you see a sign like this one it isn’t pronounced Yee Oldee. The Y isn’t a Y, it is an obsolete letter called a thorne and is pronounced th. Also, you don’t pronounce the e in Olde (or shoppe for that matter). So, it’s just plain “The Old”. Boring, I know. Robert Burchfield, who edited the Oxford English Dictionary for 30 years up until 1986, once caused quite a stir by saying that the British and American forms of English were drifting apart so rapidly that in 200 years’ time it was possible that we would no longer be able to understand one another. However, he was speaking in the pre-internet age (remember that?) and I think it is far more likely that we will soon all be speaking American English. Already I’m being bullied by software that provides an annoying red wiggly line under anything that it thinks should have a z in it when I think it should be an s, or when I spell “colour” with a u. How long before the weaker willed amongst us start to give in to this automated intimidation? Anyway, here’s one person who is happy to educate Americans on how to pronounce Worcestershire and who will always spell colour with a u. * The words “loon” and “lunatic” are derived from the French “la lune” meaning the moon and allude to the alleged strange behaviour of some people and animals at the time of the full moon. If you enjoyed this blog or found it informative, be sure not to miss future editions by signing up to our newsletter. Just click on the button below and we'll even send you an ebook of your choice for doing it. Would you like to be a guest blogger for Selfishgenie Publishing? Just email us with an outline of your blog. And you can also have a free ebook if we use your submission. Our email address is e[email protected]

1 Comment

Chris

26/7/2022 03:23:00 pm

Regarding ‘Leicester' and 'Worcester' etc.: It’s really quite simple. They are being pronounced as they are spelt… and adding 'shire' on the end is no different if you consider how vowel sounds vary with region, social class, or period in time, let alone what they follow in a word..

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is compiled and curated by the Selfishgenie publishing team. Archives

June 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed