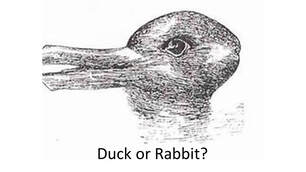

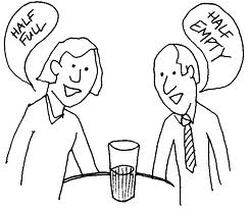

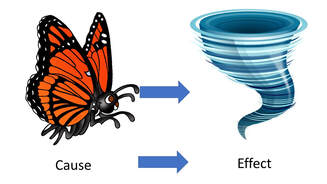

Once again I’m indebted to the users of Twitter for the inspiration behind this week’s blog. The theme is how perceptions don’t necessarily match up to reality. The Tweet(s) in question relate to an author bemoaning the fact that someone had posted rude 1 star reviews about two of her books on Amazon and she feared this was impacting on her sales. They were also undermining her confidence and making her ask herself if she should continue working on her third book. I Tweeted back (sympathetically I hope) that reviews weren’t everything and, at the end of the day they are an opinion, and no author can please everyone. If they had valid criticisms, then it was a good idea to learn from them, but otherwise forget them. There are also people who delight in posting 1 star reviews, just because they can. (I know, we live in a truly troubling world)  In her reply the author posted a screenshot of her review data, the yellow bars Amazon uses to show the percentages of reviews for each star rating. And it was highly revealing, but not in the way she thought. Out of around 240 reviews, over 60% were 5 star and another 20% were 4 star. I pointed that out, suggesting the (approx) 10% of 1 star reviews weren’t something to worry about. The number of 4 and 5 star reviews would be far more influential than the 1 star ones when it came to decisions about purchasing. She didn’t agree with me, suggesting that her KENP reads had dropped since the 1 star reviews had been posted. I suggested that she would need a bit more evidence than that in order to draw such a conclusion. Perhaps her KENP reads had dropped because her marketing activity needed refreshing. I think I may have persuaded her, because she did say she would think about that. Or maybe she was just trying to shut me up, which is a real possibility.  But it is easy to take an isolated bit of data, such as reviews, and interpret them as something they aren’t. Looking at her numbers, I would be using the percentage of 4 and 5 star reviews to trumpet the success of our books, in order to encourage new readers to try them. That screenshot she posted tells a far different story to the one she was seeing, as far as I was concerned. Because 80% reviews at that 4 and 5 star level are a real sign of success, not failure. It is always dangerous to take two bits of data, put them side by side and assign cause and effect from them. In this case a couple of 1 star reviews put alongside a drop in KENP reads equals a cause and effect.  Cause and effect? Cause and effect? A third bit of data is needed in order to see if that is a valid conclusion. In this case the third bit of data would be a measurement of marketing activity: social media posts, advertising spend etc. If there is a lot of marketing activity but a drop in KENP reads, then the author may be right in her original conclusion. But if there is a drop in marketing activity at the same time as a drop in KENP reads, then perhaps it isn’t the 1 star reviews that are the cause, perhaps it is the lack of marketing. It is very easy to let our perceptions and emotions get in the way of interpreting our data. In this case it is possible that the author is (a) underconfident and (b) sensitive to criticism. I can’t prove that because I haven’t got all the data available, but it seems to be a reasonable conclusion to draw on the basis of what she said in her Tweets.  That under confidence, combined with the sensitivity, led the author to draw a conclusion that supported her perceptions and, despite what Lee Atwater may have said, perception is not reality, it is only the perceiver’s reality. Perception may be reality, but it isn’t actuality (Bill Cowher) and you have to be able to tell the difference if you want to market your books effectively. In this case it was the perception that 1 star reviews were affecting KENP reads, when the actuality might be a lack of marketing or perhaps another, undiscovered, reason. As statisticians will tell you, correlation does not imply causation. More evidence is needed. So, if you want to diagnose problems such as drops in sales levels, what can you do?  The best thing is to use several different types of data alongside each other and see what, together, they are telling you. KDP provides you with a lot of information on sales and KENP, but it doesn’t tell you anything about your marketing activity. This means that you need to have some measurement of marketing activity that you can analyse. If you use paid advertising, there is a mountain of data that can be obtained in relation to the performance of your ads. The most important bits are conversion rates. Eg how many impressions (views) did your ads get and how many clicks on the links did that convert to. Then how many of those clicks were converted to sales. The experts suggest you should be expecting at least a 10% conversion rate of link clicks to sales to consider an advertising campaign to be successful. But if you don’t use paid for advertising, you only use social media, you have to look elsewhere for your data. But the same principles apply. How much engagement did you get for the social media posts that pitched your books? How many clicks on the links etc.  The lower the numbers are, the less likely it is that you made sales or KENP reads. If you got high engagement levels but low sales, it means that readers looked at your book but chose not to buy it and there are many reasons why that may be. Reviews are one of them, of course, but they aren’t the only one. There is your cover, the blurb and the ‘look inside’ portion of the book as well. I would say that all three of those are a more likely reason for a reader not buying than having 10% 1 star reviews when 80% are 4 and 5 star. I’m not saying reviews aren’t important. Readers often send us important information tucked away in a poor review and that information can be used to improve writing. But, as I said before, a review is just an opinion and, in some cases, it isn’t even that. It may just be some poor soul being nasty because it makes them feel good. And that contaminates the data, just as an author getting their Mum to post 5 star review contaminates the data. But importantly, don’t let perception become your reality if you aren’t sure it is also the actuality. Correlation isn’t the same as causation (well, sometimes it is but that is a whole different blog). If you have enjoyed this blog, or found it informative, then make sure you don’t miss future editions. Just click on the button below to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll even send you a free ebook for doing so.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog is compiled and curated by the Selfishgenie publishing team. Archives

June 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed